A guide to knowing your dugongs from your manatees

The dugong is the only surviving species in the family Dugongidae. There was one other modern member — Steller’s sea cow; a huge, slow-swimming northern Pacific mammal that ate seaweed and may have reached weights of up to 10 tonnes.

Sadly, the species is now best known as a cautionary conservation tale: it was discovered and hunted to extinction in three decades during the 18th century.

Dugongs belong to the order Sirenia (the sirens), the name being a nod to mermaid mythology. The other living members are three species of manatee, all found in coastal areas and rivers of the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico, the Amazon Basin and West Africa. There are similarities between the two groups, particularly their size, appearance and histories. But, in the evolutionary sense, they’ve been separated for a long time and there are significant differences.

Sirenians have a similar shape to whales, dolphins or seals, but are not closely related. They have a clearer evolutionary connection to elephants and small rodent-like animals called hyraxes, found in Africa and the Middle East.

Here are the different manatees and dugongs found around the globe:

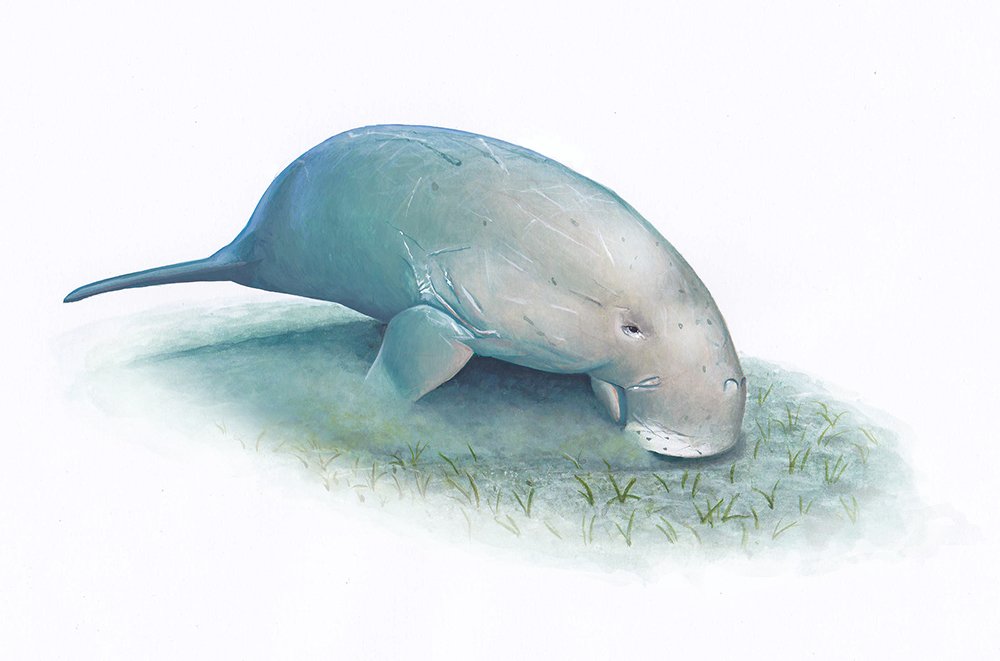

Dugong (Dugong dugon)

Dugongs are born with smooth pale skin but all eventually develop scars —the result of the tusks of adult males. Because they often fight each other, male dugongs have scarring from the middle of their back down to their tails. Males also use their tusks for leverage during mating, so females become more marked around the head and neck.

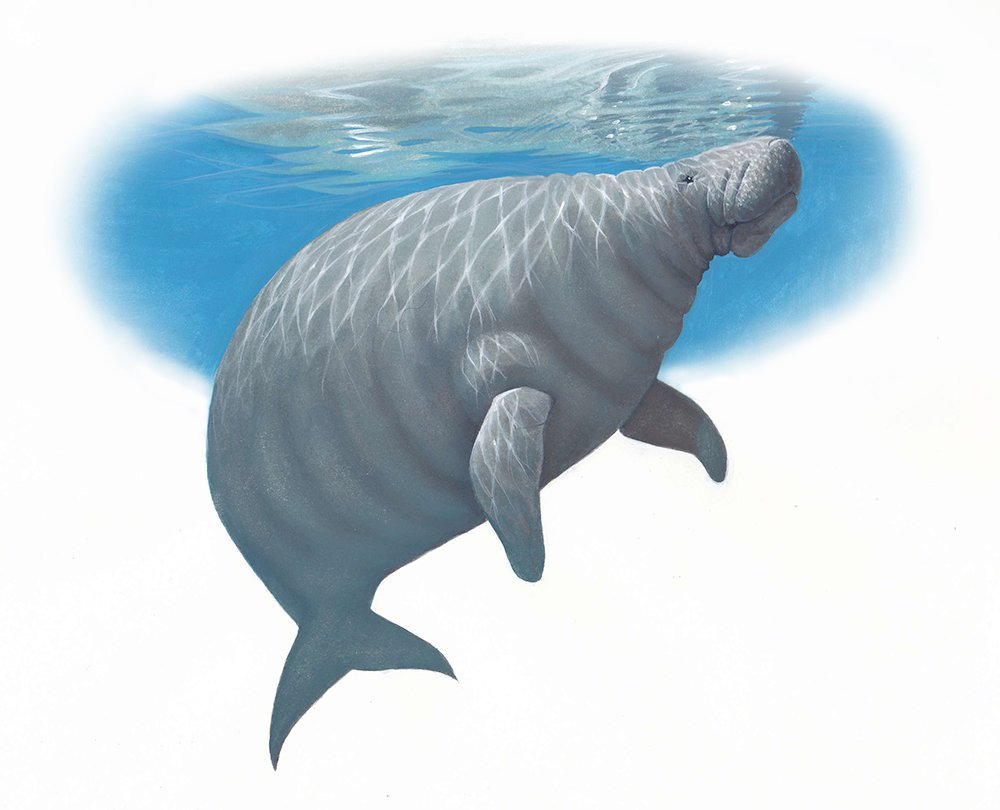

Steller’s sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas) [EXTINCT]

Unlike its surviving relatives, the manatees and dugong, this slow-moving herbivorous mammal was not a tropical species but a cold- and temperate-water specialist. Hunted to extinction in the 1700s, it was by far the biggest of the sirenians, possibly reaching lengths of more than 8m.

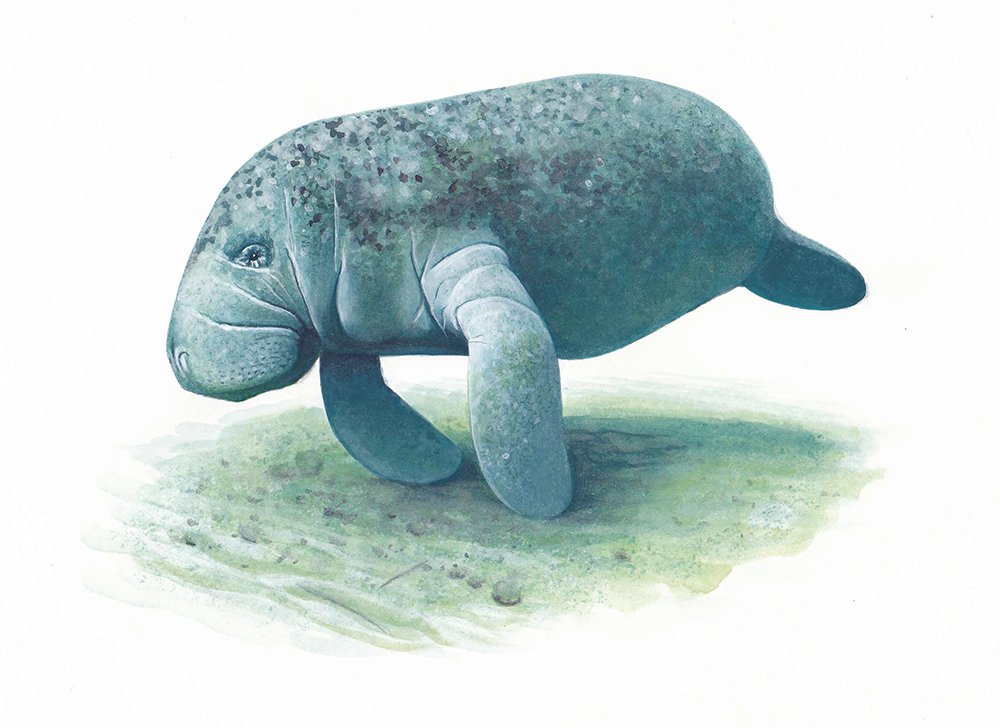

Amazonian manatee (Trichechus inunguis)

This dark-skinned mammal, described as looking like both a seal and a hippopotamus, is the smallest of the manatees and the only one to be restricted to fresh water. It occurs only in the Amazon River and its tributaries, and is believed to be critically endangered.

West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus)

An estimated 10,000 animals in two subspecies of West Indian manatee survive in waters off Florida, USA, the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico. Unlike their close relatives, dugongs, manatees can tolerate a wide range of salinities and will move easily between fresh-water rivers and the sea.

African manatee (Trichechus senegalensis)

This is the least studied of all the sirenians. It’s found in marine and freshwater habitats in equatorial waters along the west coast of Africa. Similar to other manatees, it’s known to eat a wide variety of aquatic vegetation and is even able to eat the tough waxy leaves of mangroves.