There were no Australian painted-snipes the morning I searched the drainage ditches near Brisbane Airport in November 2023. Although one had been photographed there days earlier, the wily wader eluded me.

I’m not the only one who hasn’t seen this endangered shorebird; according to BirdLife Australia, the painted-snipe is one of the 10 most difficult-to-find bird species in Australia. That not only means it’s difficult for birdwatchers to find but, more importantly, it’s also a challenge for researchers.

For most of the 20th century – up until the 1990s, when DNA testing confirmed the Australian painted-snipe (Rostratula australis) has been isolated on mainland Australia for millions of years – the bird was considered a subspecies of the greater painted-snipe (Rostratula benghalensis) of Africa and Asia. Although greater painted-snipe populations have declined markedly, it remains a widespread wetland species. In parts of Asia, for example, it’s reliably found in traditional rice paddy landscapes, where it nests in fallow fields.

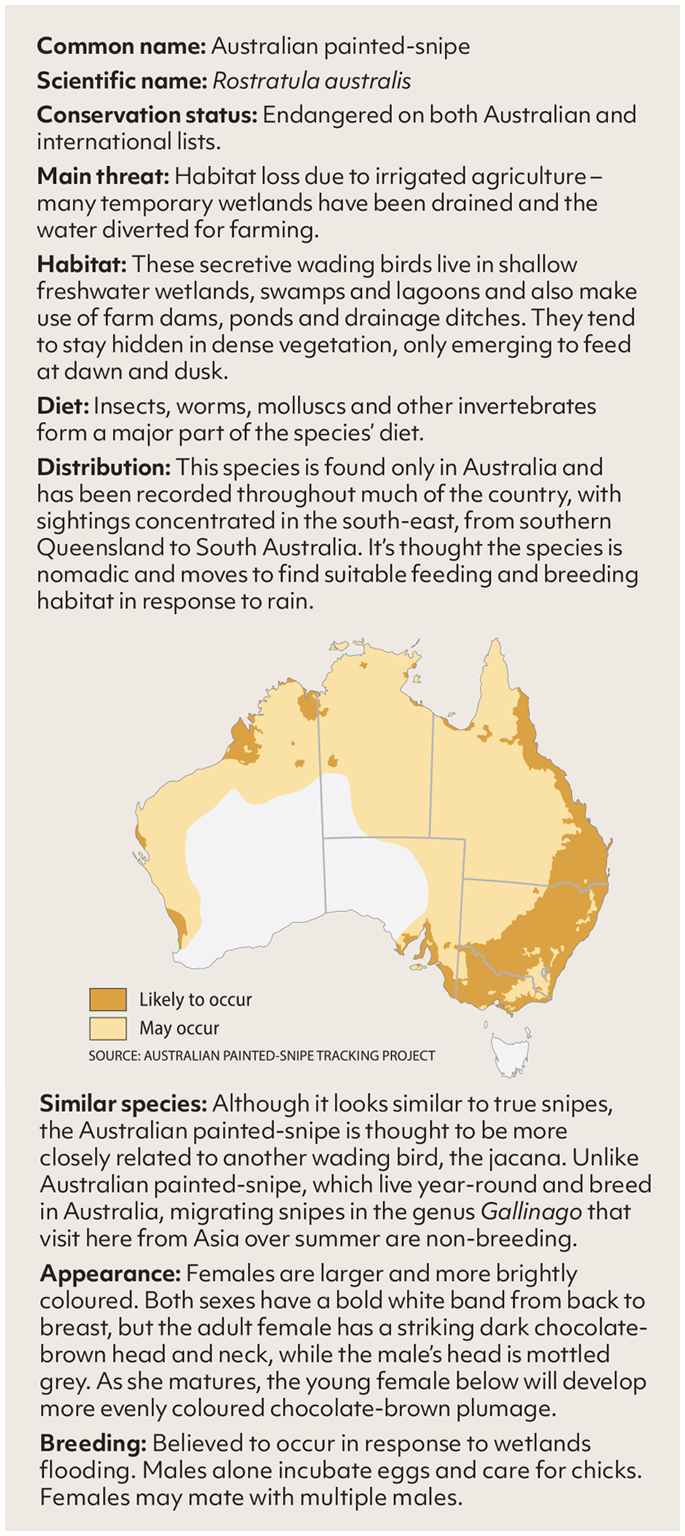

In contrast, the Australian painted-snipe’s distribution is patchy and its presence at any particular location is unpredictable. “They can turn up in very isolated wetlands that have been dry for ages,” says Dr Danny Rogers, an ornithologist with the Victorian Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action. “My guess is that [the] Australian birds are a lot more mobile than the greater painted-snipe. Their longer wings suggest that.”

Australian painted-snipe inhabit ephemeral wetlands, temporary swamps and shallow lagoons that periodically dry up and refill after replenishing rains. They probe for insects, worms, molluscs and other invertebrates in shallow water and exposed mud on wetland margins, and nest on the ground, typically among grass tussocks and reeds on small islands left by receding floodwaters.

The species is thought to be polyandrous, meaning females mate with multiple males that then incubate eggs and care for chicks. If ephemeral wetlands aren’t available, the birds make use of altered habitats such as farm dams, town ponds, and even airport drainage ditches.

Like many Australian wetland birds, the species appears to be nomadic, but little is currently known about its migratory behaviour. With so few sightings recorded, the mysterious species seemingly vanishes for months at a time.

Rare sightings

Australian painted-snipe sightings are rare and becoming rarer. Reported sightings have been declining since at least the 1950s, especially in the Murray–Darling Basin, which was once a stronghold for the species. Researchers estimate there are now only a few hundred birds left.

Concerned about a lack of sightings in 2021 and 2022, Dr Matt Herring brought together a team of shorebird experts that launched the Australian Painted-Snipe Tracking Project (APSTP). Matt, an ecologist at private conservation consultancy Murray Wildlife, and his colleagues launched the program with a crowdfunding campaign that raised more than $124,000 in only 40 days. Through the project, the team is also seeking help from the public in reporting sightings and, in a breakthrough for the species, to track the birds for the first time.

By the end of last year, 58 birds across 23 locations had been reported to the APSTP. Matt is encouraged by the spate of sightings but isn’t complacent. “With so many people on the look-out, and such great conditions, the number of birds found nationally emphasises how rare the bird is,” he says. “We know its population has declined.”

Also, very little is known about this unpredictable, cryptic bird’s ecology. Researchers are in the dark on where the elusive birds go during winter and droughts – when they seemingly vanish for months or even years at a time – and whether their habitats are secure. “A real threat is our lack of knowledge,” Matt says.

Matt, Danny and their wetland-loving colleagues plan to attach a dozen devices – a mix of satellite and mobile phone network transmitters – to individual birds to learn more about their habitat use and movements. Most sightings are in south-eastern Australia during spring and summer, and little is known about where the birds spend autumn and winter.

A smattering of sightings recorded in northern Queensland and along the coast of central Queensland suggests part of the population undertakes regular seasonal migration. Tracking may uncover their migration mysteries and, it’s hoped, reveal key sites and drought refuges.

Recording the call

With so much information to be gained, the tracking team was thrilled when a group of 25 birds was reported in a private wetland on a farm near Balranald, in the New South Wales Riverina, in October 2023. One was promptly caught in a mist net and fitted with a satellite transmitter, and Gloria, as she’s known, became the first Australian painted-snipe to have her movements tracked. Her behaviour has surprised Matt. “Already we’ve learnt that she uses dry roosts far more than I would have anticipated,” he says.

The tracking team plans to catch and track more birds at this and other sites. However, the species’ skulking behaviour, and habit of sheltering in dense vegetation during the heat of the day, means they can be hard to spot and are easily overlooked.

The team also hopes to bag a potentially useful survey tool – an audio recording of the Australian painted-snipe’s call. The greater painted-snipe makes deep loud hoots to advertise for mates and the sound often reveals their presence to birdwatchers. But the Australian painted-snipe’s advertisement call has never been recorded and the species doesn’t respond to the greater painted-snipe’s call. Presumably, millions of years of separation means they now speak a different love language.

The main threat to the Australian painted-snipe seems to be the loss of temporary wetland habitat, particularly for breeding and refuge from drought. Drainage and water diversion for irrigated agriculture have taken a toll. “Many temporary wetlands don’t exist anymore, or they have permanent water regimes that are too deep and just not suitable breeding habitat,” Danny says.

Compounding the problem, remaining wetlands are dry for longer periods due to extended droughts. “Climate change, with the increasing frequency and severity of droughts – that’s possibly their biggest threat,” Matt says.

Armed with knowledge of which wetlands Australian painted-snipe are using, the trackers will be able to engage with landholders to help them manage their wetlands to support the endangered bird. Finding the birds is the first challenge, so the team is calling on citizen scientists across Australia to join the hunt and report sightings. “Get out there and find this wetland jewel,” Matt says. “You never know where it might turn up.”