When a bronze statue of a woman named Charlotte was unveiled in Berrima, New South Wales in December 2023, it sparked conversations about who she was and why she deserved to be commemorated in such a way.

Charlotte Waring Atkinson Barton lived from 1796 to 1867. In ways that were pioneering for women of her times, she was an author, educator and great appreciator of nature and the natural sciences, and successfully fought in the NSW Supreme Court for custody of her four children. The youngest of these, born in 1834, was Caroline Louisa Atkinson Calvert, who died just five years after her mother, in 1872.

Both Charlotte and Louisa were unconventional, multi-talented women who achieved significant firsts in colonial Australia. Their stories are dramatic and extraordinary, and three prolific and award-winning Australian authors have written about them – Patricia Clarke OAM, Kate Forsyth and Belinda Murrell. Patricia’s 1990 biography, Pioneer Writer: The Life of Louisa Atkinson, Novelist, Journalist, Naturalist, is the only extended biographical writing about Louisa. It includes extended excerpts from Louisa’s novels and articles and substantial research on Charlotte.

Sisters Kate Forsyth and Belinda Murrell are great-great-great-great-granddaughters of Charlotte by her eldest daughter, Charlotte Elizabeth. They are also part of the Wingecarribee Women Writers group, which commissioned the statue by artist Julie Haseler Reilly. Their 2020 co-authored book, Searching for Charlotte: The Fascinating Story of Australia’s First Children’s Author, is about Charlotte and her children, and the authors’ personal journey as they researched the book. Given Charlotte’s life, that was quite a journey.

Like the plot of a novel

London-born Charlotte Waring was a well-educated and accomplished governess in England before she set out for Australia in 1826 to be governess for the eldest daughters of Maria and Hannibal Hawkins MacArthur. On the voyage over, she met and became engaged to James Atkinson, a successful agriculturalist with a large land grant, Oldbury, at Sutton Forest near Berrima in NSW.

After working for the MacArthurs, Charlotte married James in 1827. When he died in May 1834, she was left a widow at Oldbury with four children. Louisa, the youngest, was just two months old. Charlotte was a co-executor of James’s will but soon fell out with the other two executors, Alexander Berry and John Coghill, who took financial control of James’s estate by the terms of the will.

What happened next reads like the plot of a 19th-century novel. In 1836 bushrangers ambushed Charlotte and George Bruce Barton, the overseer at Oldbury. They whipped Barton brutally, but, one month later, Charlotte married him. He became a violent and unpredictable alcoholic and in 1839 Charlotte fled from the house at Oldbury with her children and some other people, as well as their pet koala, Master Maugie. It was a perilous two-day journey to their place of refuge – a simple dwelling at Budgong, an outstation of James’s estate in remote bushland. Charlotte moved to Sydney with the children in 1840, applied for police protection from Barton and launched a court case against Berry and Coghill to obtain funds from James’s estate. The pair retaliated, claiming that Charlotte was unfit to be the children’s guardian. She responded by fighting for their guardianship, and won.

The NSW Supreme Court (Equity Jurisdiction) case of Atkinson and Others vs Barton and Others held the children – then aged from six to 12 – as plaintiffs against the three executors and (initially) George Barton. In a resounding and groundbreaking decision on July 1841, Chief Justice Sir James Dowling granted Charlotte custody of her four children and ordered the estate to make regular payments to her – she hadn’t received any money from the estate since fleeing Barton.

It was the first time a woman was granted custody of her children in Australia and was just one of many decisions in the bitter six-year case, but it was the one that especially vindicated Charlotte. She had fiercely and persistently defended her worth as a mother and educator amid attempts, one of them salacious, to discredit her. Barton asserted she slept with convicts, something his lawyers later retracted. “Charlotte was a tigress in fighting to keep her children,” Patricia tells me. “She had to be a remarkable fighter to succeed against the entrenched prejudice of a completely male legal system.”

Kate agrees. “Someone else of a more demure character would have failed probably even to mount the case in the first place, whereas Charlotte prevailed,” she says. “My favourite quote about Charlotte is by Alexander Berry. He calls her ‘a notable she-dragon’ in a letter [in 1842] to Coghill about the case.” Berry was a powerful man in colonial Australia and for a woman to undertake such legal action was extraordinary.

Patricia believes Charlotte’s fight instilled in Louisa an underlying belief in women’s independence, which she expressed in her actions. In Pioneer Writer, Patricia notes that Louisa “demonstrated in her own life the right of a woman to study natural science, to write for newspapers and to write novels – all unusual pursuits for a woman in mid-19th-century Australia.”

Feminist values

While the court case was underway, Charlotte made literary history by writing the first children’s book published in Australia, A Mother’s Offering to Her Children by “A lady, long resident in New South Wales”. Despite the pseudonym, Charlotte’s authorship was no secret at the time, being revealed in newspapers upon the book’s publication in December 1841. Structured as a series of conversations between a mother, Mrs Saville, and her four children, the book discusses zoology, botany, geology and mining, as well as shipwrecks and aspects of Australian First Nations culture. It refers to specific occurrences, people, flora, fauna, places and objects from Australia. For the first time, Australian children could read a book set in Australia, about Australia, with Australian children as characters.

Unsurprisingly, it was also educational. Charlotte was a governess, educating her own children. She later established a small boarding school for girls at Fernhurst, the house in which she and Louisa lived from 1859 to 1865 at Kurrajong in the Blue Mountains. “It was an educational tool that I imagine was shaped by Charlotte’s thinking about what fascinated her own children, and by thinking about what she thought

was important to share with her own children,” Belinda Murrell explains.

Kate, Belinda and Patricia believe Charlotte often speaks autobiographically through the character of Mrs Saville. For example, Belinda says she and Kate interpret that Charlotte spoke for herself when Mrs Saville says: “I used to take much pleasure in a collection of shells, fossils, ores &c. which I had when in England.”

Belinda stresses how pioneering Charlotte was by so clearly portraying women’s and girls’ interest in the natural sciences. Her book substantially covers the natural sciences, and three of the four fictional children are girls.

It also conveys Charlotte’s teaching ideas. When reading it, you can easily picture a young Louisa, aged seven when the book was published, heading outdoors with her siblings and mother. Charlotte would have enthusiastically led her children to observe and discuss nature, before they all moved indoors to continue studying objects they’d gathered. Charlotte’s voice can be heard in Mrs Saville, who says to one of her children: “Change your shoes my dear, and tell Thomas to bring a tray, to spread the curiosities upon.”

A Mother’s Offering to Her Childrenis most certainly a book of its time, including the way it talks with inherent racism about First Nations people. Kate, Belinda and Patricia acknowledge this in Searching for Charlotte and Pioneer Writer. “Charlotte was fascinated with local Indigenous culture,” Belinda says. “She recorded a lot of the cultural practices of the time, and she was recording this through the filter of her 19th-century sensibilities and her Christian beliefs. I was a bit shocked to read some elements of it.”

Kate and Belinda say that despite this, the book expresses views of First Nations people that were unusually sympathetic for the time. Charlotte was expressing attitudes that she gained through the family’s positive firsthand experiences with the Wodi Wodi people of the Dharawal Nation, who passed through and congregated on the lands where Oldbury was situated. Some of the information about First Nations culture that Charlotte presents in the book appears to have been acquired during these experiences. However, Charlotte also relied on the sometimes dubious accuracy of newspaper reporting of the day.

Novel trailblazer

In 1842 Louisa’s three siblings started at the College High School in inner Sydney, established by James Rennie, formerly the Natural History Professor at Kings College, London. His daughter ran the girls’ section of this school.

While there’s no firm evidence that Louisa joined her siblings there, some clues suggest she may have done. These include an 1874 memorial sermon for Louisa by her friend William Woolls, a botanist and Anglican priest, who said, “she does not appear to have received any education after her twelfth year”. Louisa was 12 when the family left Sydney to return to Oldbury.

If Louisa had stayed home with Charlotte, evidence suggests she would still have had an excellent education. Charlotte was an accomplished educator; in England and Australia, she’d received remarkably high salaries compared with other governesses, and had competitively secured the governess role with the MacArthurs; her eldest children excelled at the College High School: Charlotte Elizabeth was named dux of the girls’ section in late 1842.

Charlotte senior’s education in England, arranged by her father, was broad in scope and high-level. “She worked as a governess from age 15 but continued to work with masters,” Belinda says. Those masters included esteemed artist John Glover, who taught Charlotte to paint. Charlotte passed on what she’d learnt from them to Louisa.

In 1857, at the age of 23, Louisa became the first Australian-born woman to publish a novel, when Gertrude the Emigrant, A Tale of Colonial Life was published, under the pseudonym “An Australian Lady”, illustrated with her drawings.

Louisa wrote five more novels between 1859 and her death in 1872. The last four appeared as serials in The Sydney Mail under the initials L.A., and then L.C. after she married James Snowden Calvert, the botanist and explorer who went on Ludwig Leichhardt’s successful 1844–45 expedition.

Louisa began a career in journalism in 1853, at the age of 19, writing and drawing for The Illustrated Sydney News. She went on to become the first Australian-born woman to have a long-running series of articles in a major Australian newspaper. Her series “A Voice from the Country” ran from 1860 to 1870 in The Sydney Morning Herald and The Sydney Mail, both then owned by Fairfax. Louisa’s articles were mostly nature-themed, but she also wrote about First Nations culture, and with a sympathy unusual for the period.

She even wrote of First Nations Australians being the “original possessors” of land “invaded” by “so-called Christian people” in 1863 in one of her “A Voice from the Country” articles. Talking about it, Kate says, “Louisa’s attitudes were startlingly modern for the time.”

Louisa’s novels richly detail Australian colonial social and agricultural life. She never explicitly presented the dramatic family troubles of her childhood in her texts but, no surprise, there’s one featuring wills and guardianship.

“I think Louisa did it very well in Tom Hellicar’s Children [first published in 1871 in The Sydney Mail],” Patricia says. “It brings out the type of conflict, though she portrays a very different woman from her mother.”

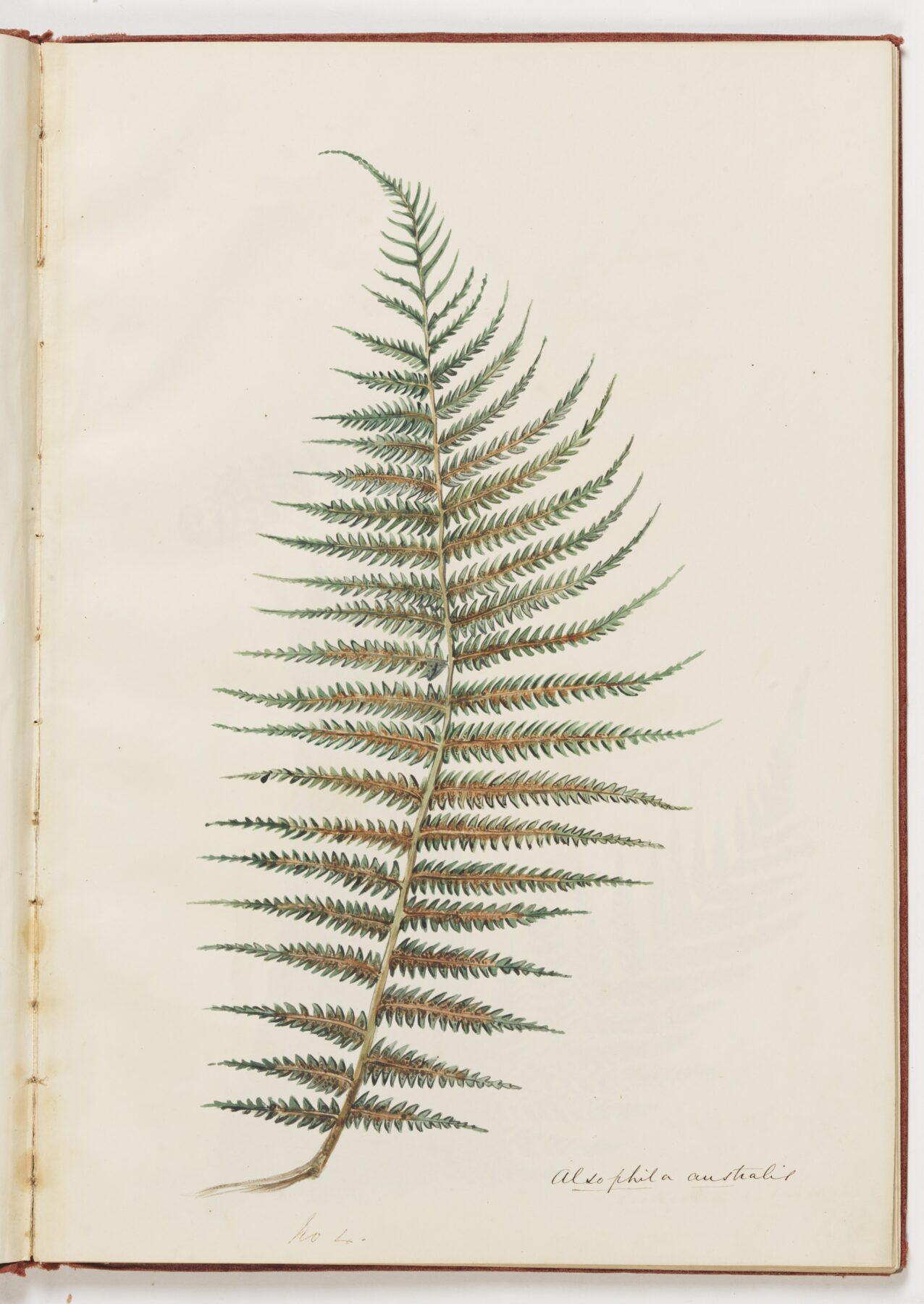

Louisa also contributed specimens with contextual information to people then central in the Australian natural sciences. Most notably, she provided hundreds of botanical specimens to Baron Ferdinand von Mueller, the government botanist of Victoria, then also the director of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Melbourne. A mark of his high esteem for Louisa’s abilities is his naming one genus and four plant species after her, referencing either Atkinson or Calvert. Another is his liaison with his contacts in Germany on behalf of Louisa, about the publication of a natural history of Australian fauna featuring plates of Louisa’s watercolours. Sadly, this book didn’t come to fruition, scuppered by the Franco-Prussian War and then Louisa’s death in 1872.

Immortalised in bronze

The bronze statue erected in Berrima Marketplace Park in Berrima in 2023 portrays Charlotte sitting on a sandstone plinth, holding an open book and surrounded by four sandstone blocks, each inscribed with one of her children’s names. It’s a celebration of Charlotte’s successes, legal and literary.

A quote from A Mother’s Offering is inscribed on the plinth: “We should never, my dear children, say we cannot bear this or that. It’s impossible to put bounds on human endurance.”

Searching for Charlotte and Pioneer Writer both present Charlotte as brave, independent, determined and tenacious – attributes that would have helped her endure the traumatic years after James’s death and the court case.

As it turned out, Louisa spent all her life with Charlotte, until Charlotte died in 1867. Louisa died only five years later, aged 38. Charlotte was undoubtedly a strong influence in Louisa’s life and instrumental in her phenomenal accomplishments.

Read more about the fascinating lives of these women, and you’ll help to redress one of the most astonishing things about them – that they’re not more widely and fully known.