The year 1888 saw the nascent art of photography change forever when American inventor George Eastman introduced the first Kodak hand-held box camera to the world.

With the click of a shutter, photography was transformed from the province of the professional, to a pastime for all. Easily loaded acetate roll film replaced glass plates and portable cameras began recording everyday events as never before. Photography was democratised and it would reveal the reality of life on the front.

Compact cameras equipped with collapsible bellows were developed in the 1890s, but the next big change came in 1912 when Kodak sold the first of its so-called Vest Pocket models.

The Vest Pocket Kodak (VPK) was small enough for one’s ‘vest’ or waistcoat pocket, or a woman’s purse. It was an instant hit, and by 1926 the most popular model, the ‘Autographic’, had sold more than 1,750,000 units worldwide. The VPK was advertised as the ultimate go-anywhere accessory, “…always with you, never in the way”.

A holiday spent without a Kodak was a holiday wasted.

With the camera now in the hands of the masses, it was inevitable that it would come to record events far removed from the everyday; the common man would soon be documenting his personal role in world history.

On 25 April 1915, World War I began in earnest for Australia as our troops landed at dawn at what became known as Anzac Cove on Turkey’s Gallipoli Peninsula. Just days later, Kodak’s advertising pitch moved from holidaymakers to promoting the VPK as the ‘Soldier’s Kodak’.

Rather than being carried in a waistcoat, the VPK could now fit snugly into the breast pocket of a soldier’s tunic.

The perfect present for a soldier

Tens of thousands of young men were embarking on the adventure of a lifetime.

“The recruitment campaign sold the war as a chance to see the world,” says Alison Wishart, senior curator of photographs at the Australian War Memorial (AWM), Canberra. It implied that “it was an unprecedented opportunity for an undreamt of holiday, and the enlisting soldiers were out to document their experiences in a light-hearted way”.

The young men’s travels could now be recorded for posterity, so what better gift for the departing soldier than a Kodak? And for those left behind, the Kodak offered the chance to send to the front precious keepsakes to treasure in times of stress and mortal danger. Kodak’s promotion of the VPK as the Soldier’s Kodak continued throughout the war.

Early advertisements declared the camera was “as small as a diary – and tells the story better”. Each soldier had a chance to ‘keep a lasting record of the brave part he and his company is playing in the Great War’. And with the fighting in Europe a bloody stalemate by 1916, a soldier’s snapshots would prove of incalculable value, Kodak claimed, their worth ‘only measured by the immensity of the war itself’.

Yet however much Kodak promoted the idea of the soldier at the front wielding his VPK as readily as his rifl e, the generals and their political allies – at least on the British side of the barbed wire – soon had other ideas.

After the first Allied defeat of the war, at the Battle of Mons in August 1914, the British commander-in-chief, Lord Kitchener, acted swiftly.

All correspondents and professional photographers working for British newspapers were, in the words of Australia’s official war historian, Charles Bean, “routed out” from the retreating forces.

And as the fighting turned to protracted slaughter, it became evident that manipulation of public opinion would be necessary to preserve the war effort.

An order banning photography at the front was issued in December 1914, but that did not stop one of the most famous incidents of the war being emblazoned in the press.

On 8 January 1915, photographs of the so-called Christmas Truce taken by soldiers were published in the Daily Mirror and the Daily Sketch. The sight of German and British soldiers posing together caused a sensation; it suggested that the enemy was human too, and not the cruel fiend depicted in propaganda.

There was now a ready market for soldiers’ photographs, and outrageous sums were soon being offered for the most newsworthy subjects.

Kodak used the lure of prize money to boost sales of the VPK. “£20,000 for News Pictures… Win some with a Vest Pocket Kodak”, trumpeted an advertisement in The Sydney Morning Herald of 4 May 1915.

London’s Daily Mail and Daily Mirror would pay £1000 for “even a single photograph”, the ads claimed.

To a private on just six shillings a day, the attraction must have been overwhelming. But what the advertisement failed to mention was that the War Office had placed a complete ban on soldiers carrying cameras.

Now, only photographs of propaganda value were to be disseminated, provided they were first expunged of anything deemed sensitive, and no photographers were to be allowed near the Western Front, except for accredited staff officers.

Unauthorised possession of a camera was punishable by hard labour and, technically, even death. Some still took the risk, but further images taken at the front by ordinary soldiers would become rare.

Photographic coverage of Gallipoli

HOWEVER, AT GALLIPOLI and in the wider Dardanelles campaign, as well as in Egypt, Sinai and Palestine, the rules were somewhat relaxed.

Early in the war, Australia did not use official photographers. Their contribution came later on the Western Front with the establishment in 1917 of the Australian War Records Section.

Much agitation by Bean and the Australian High Commission in London eventually led to the appointment of two of the most remarkable individuals ever to plant the legs of a camera tripod onto a battlefield – the Australian polar explorers Frank Hurley and Hubert Wilkins.

Australian photographic coverage of the Gallipoli campaign relied on the efforts of the officers and men in the trenches and dugouts – as well as those of Charles Bean as Australia’s official correspondent, and Phillip Schuler, as correspondent for Melbourne’s The Age. There was also limited coverage of the Australians by the official British photographer, Lieutenant Ernest Brooks.

Alison estimates that of the 6332 Gallipoli images from 1915 in the AWM’s collection, soldiers took about 60 per cent. Of the men who fought at Gallipoli, possibly half – a staggering 25,000 or so – carried cameras, as did some of the nurses tending the wounded on nearby Greek islands.

Later, in Palestine in 1918, Frank Hurley commented that: “the Kodak appears to be part of the equipment of the Light Horse”.

Kodak’s advertising had certainly paid off.

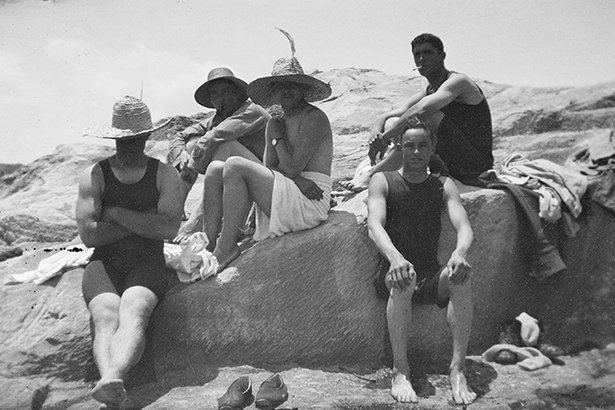

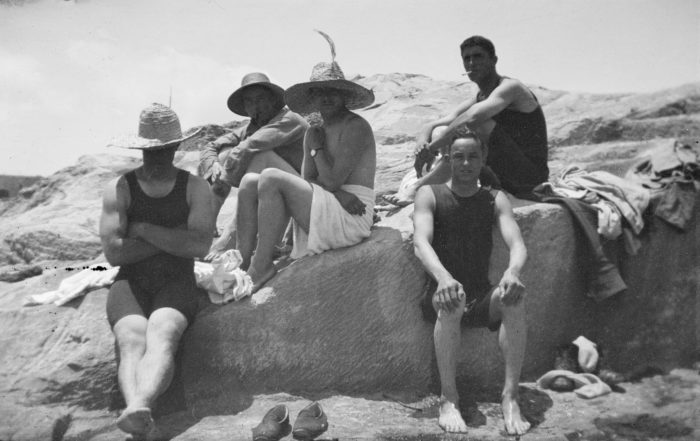

From the ordinary private, to men who would later forge significant careers in both war and peace, such as Lieutenant, later Sir, Wilfrid Kent Hughes (Olympic athlete, politician and cabinet minister), each recorded in pictures their own experience of the war.

A few, like Sergeant James Campbell of the 8th Light Horse Regiment, were professional photographers prior to the war, while some, such as Colonel Charles Snodgrass Ryan, assistant director of medical services for the Australian forces, had been keen amateurs.

Nearly all soldier photographers, though, were rank novices. Because of their limited skills, humble equipment, and the perilous conditions they endured, photographs of Gallipoli were rarely masterpieces of sharp focus or composition. But what they lacked in technique was compensated for by their “poignant simplicity”, according to Alison.

In the prelude to battle the men would understandably “reach for their rifle and helmet rather than their camera. And as much of army life is taken up with boredom and waiting rather than action, which is precisely what many of the Gallipoli images portray,” she adds.

The photographs possess a “benign quality” as they show men going about their daily lives, cooking, carting supplies, or simply passing the time, while they waited for combat.

Theirs is a collective portrait of ordinary life in extraordinary circumstances. As such, the photographs capture a moving and stoic reality. At some risk of being ensnared by the edicts of the British authorities, such images were sent home in the mail or with returning soldiers.

When they reached Australia, papers such as The Sydney Mail snapped them up and published frequent picture spreads on the Gallipoli campaign.

Seeing the commercial potential, a number of soldiers even moved to copyright their work.

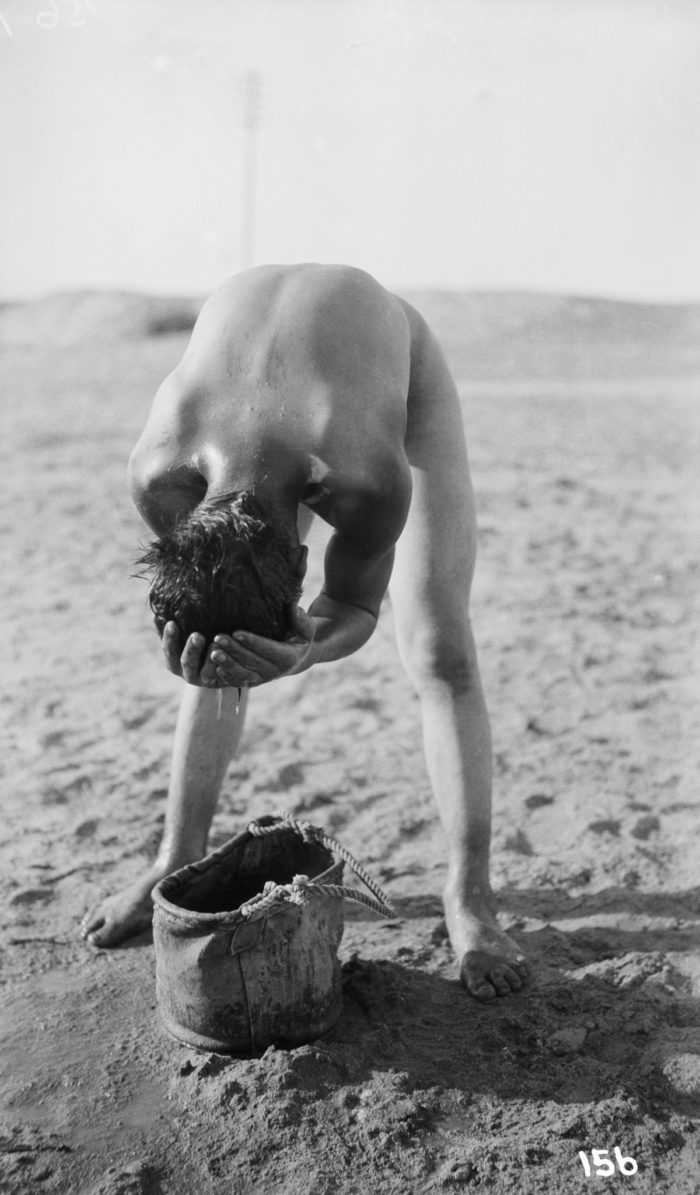

A few – such as James Campbell and George Cox of the 4th Field Ambulance, who had mastered the mysteries of the darkroom prior to the campaign – actually processed their films in situ.

They obtained powdered darkroom chemicals and photographic paper among incoming supplies or brought them back from leave. However, most waited until they were away from Gallipoli, or entrusted their precious results to mates heading for rest or medical treatment in Egypt or Britain.

Exposed rolls of film could wait months in hot and dusty or cold and wet conditions before being processed; precious images could easily be spoilt.

Photographers of World War One

Medical officers and engineers who were not directly involved in the fighting had the luxury of being able to keenly observe life in the trenches and dugouts.

Among them was the aforementioned 61-year-old Charles Ryan.

By the time he came to Gallipoli, Ryan had already lived a remarkable life. He had tended Ned Kelly’s wounds at Glenrowan, and, ironically, served as a young medical officer with the Turkish Army during conflicts with Serbia and Russia in the 1870s.

He now faced old friends across No Man’s Land.

Ryan photographed life in the trenches and dugouts with an assured and compassionate eye. He also documented the improbable terrain of the Gallipoli battlefields and photographed the armistice of 24 May when both sides gathered their dead from the killing fields between the trenches.

An Australian chaplain, Padre Walter E Dexter, also wielded a camera at Gallipoli. With his pastoral concern for suffering, some of Dexter’s images have a confronting starkness to them – lines of bodies shrouded in blankets lie awaiting burial, or the sombre poignancy of the armistice.

According to Alison, it was as if Dexter was struggling to make sense of such wholesale destruction through his photography.

Writing in The Sydney Mail in 1929, former signaller with the Australian 2nd Division, Albert Edmonds, recounted that as a keen photographer he had enlisted with enthusiasm, looking forward to “six shillings a day thrown in for films or other incidentals (mainly vin blanc)”.

Like so many, Edmonds was presented with a VPK as a farewell gift and it “worked overtime on the troopship and in Egypt”. This exotic land proved to be a photographer’s paradise.

The locals did a healthy trade in processing services. Sometimes photographs were given the ultimate personal touch and made into postcards to send home.

Prominent antiquities or the famous sites of Egypt made popular subjects for postcards, and with groups of mates snapped at such locations, the images became the ultimate ‘selfies’ of their day.

Albert Edmonds wrote that he arrived at Gallipoli “48 hours before a big stunt”. The curious photographer had “ample time to explore” and with little heed for danger sought out the best vantage point.

“This natural instinct lured me to the top of Walker’s Ridge,” he recalled, “but before the camera could be got into action there was a swish and a bang which landed behind me. Suddenly a hand shot up from the bowels of the earth and dragged the would-be photographer down. I had nearly stumbled into a gun emplacement, and got roundly cursed.”

Fearing being caught, Edmonds sent his camera home on reaching France, but soon regretted the move “as this, too, was a photographer’s paradise”. Borrowing a camera that one of his mates had secreted in his kitbag, Edmonds was back in business and went on to take clandestine photographs at Ypres and Pozières.