Gallery: AG Art Calendar covers

1989. Tree-dwellers, the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) and the eastern rosella (Platycercus eximius).

While the colourful rosella is a familiar site in woodlands, farmlands, parks and suburban gardens in the eastern states and the south-east of South Australia, the koala, which also lives in these states, is less frequently seen in the wild these days.

Buy the 2011 Australian Geographic Art Calendar: Colour in nature

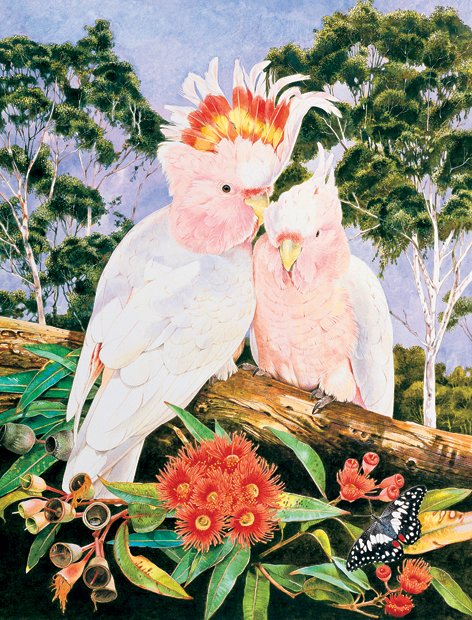

1990. Major Mitchell’s cockatoo (Cacatua leadbeateri). It’s named after the explorer Sir Thomas Mitchell, who wrote of it on his journey through inland New South Wales in 1835: “Few birds more enliven the monotonous hues of the Australian forest than this beautiful species whose pink-coloured wings and glowing crest might have embellished the air of a more voluptuous region.”

In the foreground is a red-flowering gum (Eucalyptus ficifolia) and a chequered swallowtail butterfly (Papilio demoleus sthenelus)

Buy the 2011 Australian Geographic Art Calendar: Colour in nature

1994. The orange-thighed tree frog (Litoria xanthomera).

Living in the tropical rainforests of north-east Queensland, this frog can hop but usually finds its food by climbing: its broad sucker-tipped toes can grip the smoothest leaf. As long as the green katydid (Tettigonia viridissima) remains still, it is safe. Like most frogs of its kind, the orange-thighed tree frog has horizontal-shaped pupils and only responds to moving prey.

Buy the 2011 Australian Geographic Art Calendar: Colour in nature

1995. A pair of double-eyed fig-parrots (Cyclopsitta diophthalma macleayana).

Australia’s smallest parrot species pictured with a red lacewing butterfly. The green fruit of the cluster fig has enticed the fig-parrots from the upper canopy of the north Queensland rainforest. These plump 13-cm long birds love fig seeds, and the drizzle of pulp they produce when messily extracting them from the fleshy fruit is often the only clue to where they’re perched in dense foliage. The figs are partly hidden by the heart-shaped leaves of a pepper vine, which takes root on the forest floor and climbs trees to the sunlight.

Another climbing plant, the poplar-leafed adenia, is the preferred food of red lacewing caterpillars It’s not unusual to find the Cooktown orchid, Queensland’s spectacular floral emblem, near fig-parrot perches. Its tiny seeds often take root high above the forest floor, in the rotting leaves and bark that collect in tree forks and hollow limbs.

Buy the 2011 Australian Geographic Art Calendar: Colour in nature

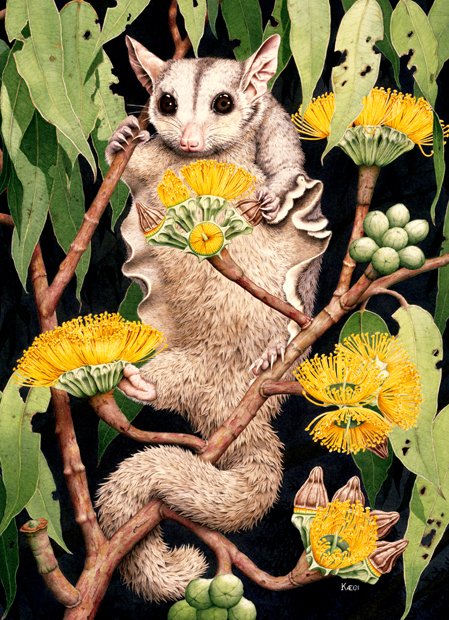

1996. A sugar glider (Petaurus breviceps).

Here climbing high into the golden blossoms of a Darwin woollybutt. It is the most widespread of Australia’s six species of glider – all of which are closely related to possums. Their agility as climbers is matched by another remarkable skill – an ability to glide from tree to tree on a pair of membranes stretched between their hind and forelimbs to form an aerofoil.

Sugar gliders are resourceful foragers, dipping their snouts into hollow tree trunks to lap up sticky sap, and catching spiders and insects – even unwary birds. They are sociable animals, with as many as seven adults and their young sharing a nest of leaves in a hollow tree, and sleeping and grooming each other during the day. As dusk falls they leave separately to find food, but if it is plentiful, they eat together, shrieking to warn each other if danger approaches.

Buy the 2011 Australian Geographic Art Calendar: Colour in nature

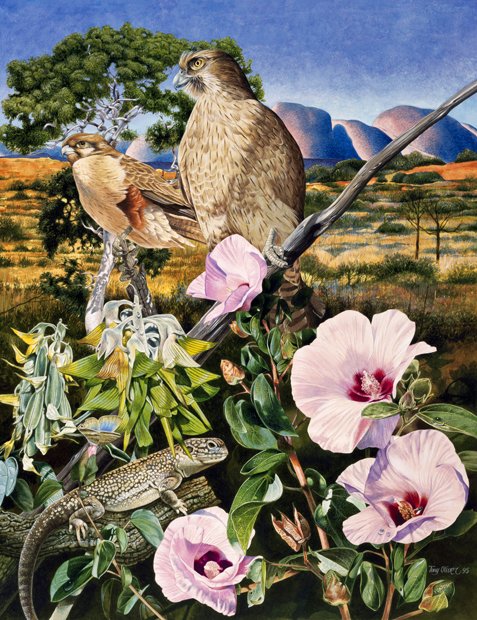

1997. The brown falcon (Falco berigora).

This widespread bird of prey is better known for its terrestrial agility – long legs and short feet make running and jumping easy – than its stunning aerial displays. Unlike most other raptors, its flight lacks grace and speed and it rarely hunts on the wing, preferring to perch quietly on fences, power poles or exposed branches. From these vantage points it is well positioned to snatch a tasty meal such as the central netted dragon (Ctenophorus nuchalis), which lacks the spiny armour of many other desert dragons.

The delicate lilac flowers of the Sturt’s desert rose (Gossypium sturtianum), the Northern Territory’s floral emblem, are a common sight in the falcon’s Red Centre hunting grounds. The parrot pea (Crotalaria cunninghamii), here being visited by the pea blue butterfly (Lampides boeticus), gets its name from the birdlike shape of its pale-green, striped blooms. During spring, the parrot pea blooms in abundance near the red sandstone domes of Kata Tjuta, which is only a little less celebrated than neighboring Uluru.

Buy the 2011 Australian Geographic Art Calendar: Colour in nature

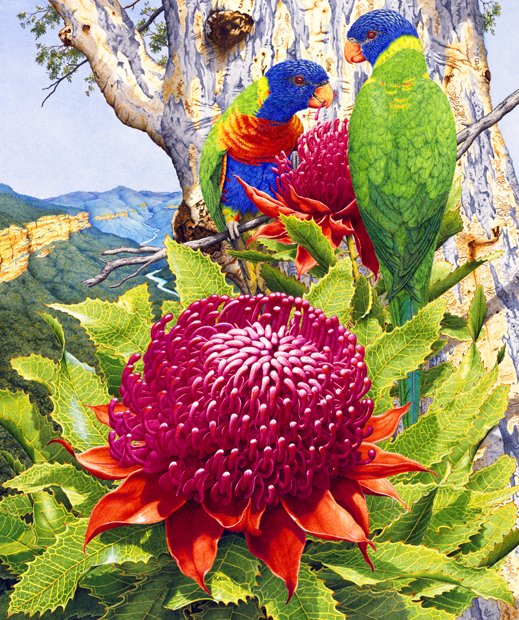

1998. A pair of rainbow lorikeets (Trichoglossus haematodus) and the NSW Waratah (Telopea speciosissima). Considered by early settlers to be the most beautiful plant in NSW, the flower is now that State’s floral emblem – the only one in Australia known by its aboriginal name.

Waratahs are fertilised mainly by birds such as lorikeets, which are equipped with brush tipped tongues to probe for nectars. This pair has a nest nearby in a hollow limb of the broadleaved scribbly gum (Eucalyptus haemastoma), often a home for birds and small mammals. Common in these nutrient-poor, sandy soils, the gum takes its name from the erratic meanderings of tiny moth larvae that burrow beneath the bark, decorating its trunk.

Buy the 2011 Australian Geographic Art Calendar: Colour in nature

2000. Laughing kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguineae) Listen to its sound

It lifts its head and opens its beak, preparing to let loose with one of the most familiar and distinctive sounds of the bush. The cacophonous chortle, usually heard at dawn and dusk, is a statement of the territorial ownership, and once this bird starts cackling from its stage on a spotted-gum branch, its partner will quickly join in.

Kookaburras are the world’s largest kingfishers, but they rarely eat fish. Famous in folklore for catching and eating snakes, they’re opportunists that devour lizards, small birds, insects and, of course, the odd barbecued sausage. They lived only in open forests in eastern Australia until they were introduced into Australia’s southwest, Tasmania and New Zealand. The pair, bonded for a lifetime of 20 years or more, has excavated a hole in a tree-termite nest near the spotted gum, into which the female will lay 2-4 round, white eggs.

Buy the 2011 Australian Geographic Art Calendar: Colour in nature

2004. King parrot (Allisterus scapularis).

Pairs or small flocks of these birds spend much of the day resting quietly in trees and shrubs, feeding on fruits, blossoms, nectar and buds among the outer branches, and sometimes foraging on the ground for fallen seeds. King parrots that aren’t used to humans are wary and difficult to approach, but in popular national parks they can be more trusting.

Buy the 2011 Australian Geographic Art Calendar: Colour in nature

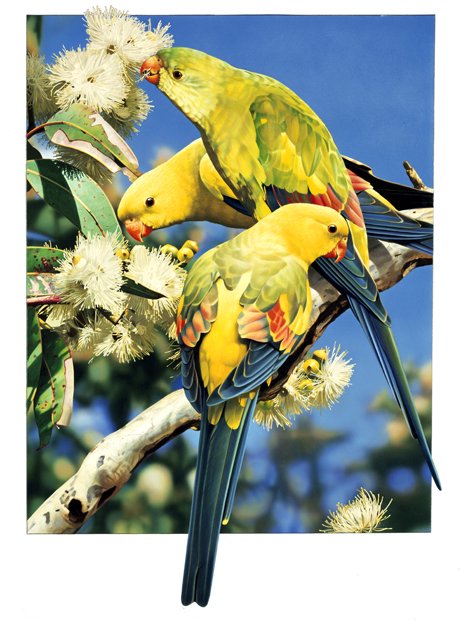

2005. A trio of regent parrots (Polytelis anthopeplus).

These attractive birds are feeding on eucalypt blossoms, but they also spend much of the day on the ground taking seeds, nuts and fallen fruit. Two widely separated populations occur. Those living in the mallees and river red gums of eastern Australia have severely declined from habitat loss. In the west they remain common and gather in flocks to feed on cereal crops and orchards. Regent parrots require large old eucalypts with deep insulated hollows as nesting sites and it is feared the loss of these trees may cause future declines in the numbers of these western birds.

Buy the 2011 Australian Geographic Art Calendar: Colour in nature

2007. Gouldian Finch (Erythrura gouldiae)

Who can deny the Gouldian finch its status as one of Australia’s most striking birds? Those brilliant hues practically collide. This trio features the two dominant colour forms. About three quarters have black faces, while nearly a quarter are red-faced. A third golden-headed form is extremely rare. The highly social Gouldians live in flocks on tropical open grassy woodlands, never far from permanent water. They feed on native grass seeds and lay their oval white eggs in tree hollows. In captivity, Gouldians are popular, hardy and easy to breed; yet, numbers in the wild have crashed to alarming levels, triggering frantic efforts to reverse the trend. Likely culprits in the birds’ decline are the effects of cattle grazing, introduced pasture grasses and changes to fire regimes.

Buy the 2011 Australian Geographic Art Calendar: Colour in nature

2008. Princess or Alexandra’s parrot (Polytelis alexandrae)

It is a lucky person who gazes upon the splendour of a princess parrot. The mysterious and elusive bird is restricted to some of Australia’s most remote and arid country. Hailed as among our most beautiful parrots, this species is graced with subtle pastel colours, a slender body and long tail. Several pairs may appear at a tree-lined desert watercourse, rear their young then vanish for years or decades. They nest in hollows, particularly eucalypts, but generally feed on or near the ground, favouring spinifex seeds, wattle flowers and mistletoe berries. They are swift and slightly undulating in flight but, when perching, princess parrots have a distinctive habit of lying low and lengthwise on a branch, rather like a lizard.

Buy the 2011 Australian Geographic Art Calendar: Colour in nature

2009. Rufous Fantail (Rhipidura rufifrons)

Rufous fantails are instantly recognisable by their pertly splayed rust-coloured tails, fidgety behaviour and confiding nature. Both parents use fine grasses and soft bark, bound with spider webs to construct a wineglass-shaped nest – featuring a 70-cm pendant tail – well hidden in dense thickets. These attentive parents share the responsibility of catching insects and feeding their brood of two to three young. If disturbed, they’re reluctant to leave the nest and impatient to return.

Birds living south of southern Queensland are strongly nomadic, with adults heading north around February, and juveniles following a couple of months later. During this time they often move through open country, away from their preferred forest habitats. Northern birds are more sedentary, though they shift up from lowlands to the mountains to breed.

Buy the 2011 Australian Geographic Art Calendar: Colour in nature

2010 Rainbow bee-eater (Merops ornatus)

The rainbow bee-eater is widely distributed across mainland Australia. Although it lives mostly in open forests and woodlands, it has also been recorded in a particularly wide range of other habitats from mangroves, farmlands, heathlands and vine thickets to sand-dune systems.

Like other bee-eaters, this species nests in ground burrows up to 1.5 m in length, sometimes situated in colonies, along creek and river banks and cliff faces. Both males and females excavate these burrows using their feet. Although rainbow bee-eaters nest in monogamous pairs, the chicks are often attended by helper males. Unlike most other birds, rainbow bee-eaters have no nest sanitation and the burrows can develop a distinctively pungent odour. As their name implies, these birds eat bees but they also catch many other insects on the wing.

Buy the 2011 Australian Geographic Art Calendar: Colour in nature

Home Topics History & Culture Gallery: AG Art Calendar covers