OPINION: Return Aboriginal sacred objects

SEVERAL YEARS AGA, traditional owners from Gunbalanya in western Arnhem Land asked the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, to return a collection of their ancestors’ remains.

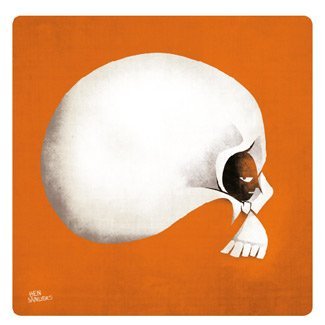

In what the ABC later referred to as “modern day head-hunting”, the museum first offered to return some human bones, but wanted to keep their collection of skulls.

Happily, all the remains were eventually returned to the Gunbalanya community in 2010. However, the controversy highlighted an ethical dilemma at the heart of any cultural collection.

On one hand, objects may hold universal values: they help us understand and celebrate humanity, and deserve to be kept for future generations. But those same museum objects may also hold values that are specific to the community that created them, and, as part of an active cultural tradition, they may equally deserve to be returned to the original owners.

Hanging tjuringas back to Aboriginal communities

I have been lucky enough to work with museum collections of tjuringa, or Aboriginal sacred objects from central Australia. Beautifully polished and carved, thousands of these stunning artworks were taken from the Aboriginal people of central Australia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

They were eagerly sought by museums and art collectors worldwide, despite their role in Aboriginal ceremony and strict traditional rules of secrecy that could have women or uninitiated men killed simply for looking at one.

One of the great privileges of my working life has been to witness events where tjuringa were handed back from a museum collection to their traditional owners. Greeting their returning tjuringa, I have seen men stroking, speaking and singing to these objects as if they were a much-loved relative returning home.

Hinting at a deeper truth

Perhaps this hints at a deeper truth. The literature for central Australia describes sacred objects as the literal manifestation of the Dreamtime ancestors that created the Earth – not a representation of the ancestors, but the ancestors transformed; not just a key to ceremonial life, but also a key to life itself. There are ceremonies that cannot be performed without the proper object, in the same way they cannot be performed without the proper people.

As part of a living culture, in a sense, these objects have a life of their own. They don’t belong in a museum.

For the past 10 years, all major Australian state and territory museums have been participating in a Commonwealth-funded repatriation program. Thousands of skeletal human remains and sacred objects have been returned, but thousands more remain in collections. Repatriation often involves years of research and negotiation with indigenous communities, as complex issues of identity and ownership are resolved.

It can take years for communities to resolve how to manage, in a modern context, the traditional cultural protocols associated with secret, sensitive, and even dangerous ritual material. I’m confident the work will go forward, but looking at the wider picture nationally and internationally there are some issues of concern.

The first is the active trade in Aboriginal sacred objects. Search online and you are almost guaranteed to find pictures of objects for sale – a distressing violation of cultural protocol.

Ritual materials and traditional cultural protocols

While private collectors are mostly responsible, in 2010 an American museum publicly auctioned its Australian sacred objects to raise funds. Fortunately, most international museums want to behave ethically, but there are thousands of Aboriginal sacred objects overseas. To my knowledge only a handful of these have yet been successfully repatriated to an Aboriginal community.

Perhaps the biggest question of all is whether we should be repatriating much more than sacred objects and ancestral remains.

Late last year Wiradjuri elder Stephen Ryan, from central NSW, challenged the Australian Museum for holding what he called “a warehouse full of our artefacts”. He called for Aboriginal people to have wider control, noting that “all of our memories, sites and artefacts are sacred”.

I don’t pretend to have the answers, but I know we need to talk and listen to the Aboriginal community. I, for one, do not want museums to be seen as modern day head-hunters.

Dr Scott Mitchell is Head of Culture, Conservation and Business Services at the Australian Museum in Sydney. He has over 20 years of experience in heritage conservation.

Source: Australian Geographic, Issue 110 (Sep – Oct, 2012)

RELATED STORIES