Australian bird flu cases: the potential impact on humans and native wildlife

Diagnostic testing at CSIRO’s Australian Centre for Disease Preparedness at Geelong in Victoria has confirmed it as the highly pathogenic H7N3 strain of avian influenza, or ‘bird flu’.

The strain was detected after an investigation into unexpected poultry deaths on the farm.

Agriculture Victoria released a statement saying the property has been placed into quarantine with a reported 400,000 birds being “depopulated”, and that staff are on the ground to support the business and investigate further.

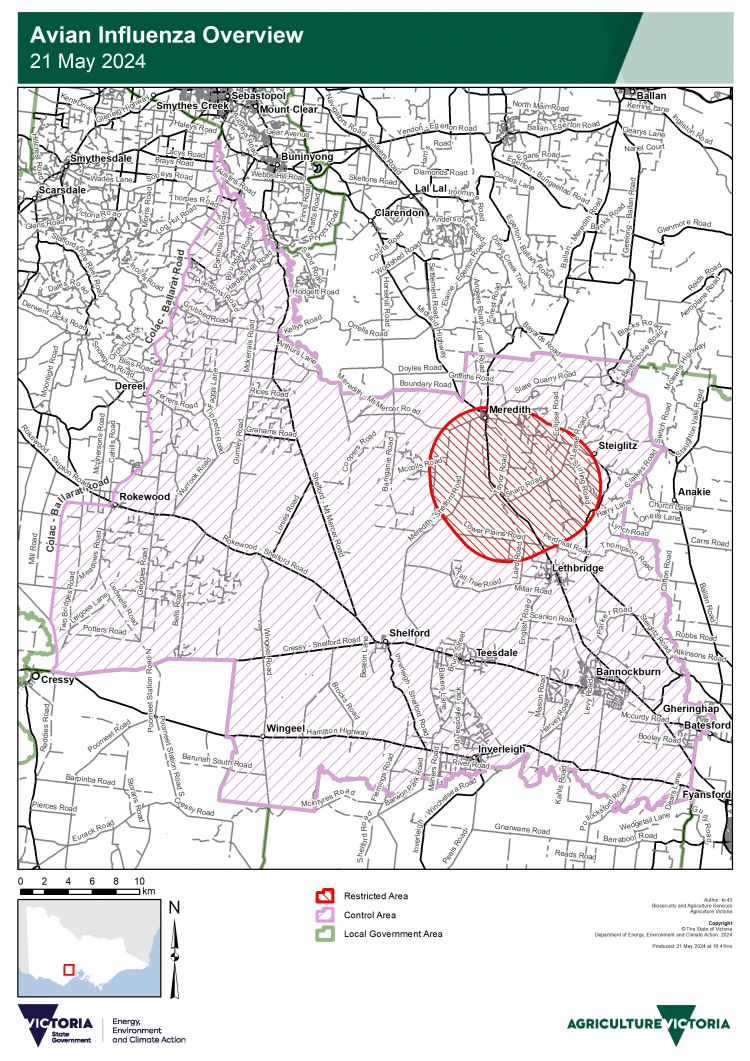

“Movement controls are now in place to prevent any spread of avian influenza. This includes a Restricted Area covering a five-kilometre radius around the affected property and a broader Control Area buffer zone covering a zone off [sic] 20 kilometres around the affected property.

“The Control Area Order requires permits for the movement of poultry, poultry products and equipment on or off the properties in these areas. Penalties apply for those who do not follow these restrictions.”

What is bird flu?

Avian influenza is a viral infection most prevalent in birds. There are a variety of subtypes and strains, with strains classified as ‘low pathogenicity’ (LPAI) and ‘high pathogenicity’ (HPAI) in relation to poultry.

Professor Raina MacIntyre, Head of the Biosecurity Program at the Kirby Institute at the University of NSW, says the virus is typically spread by wild birds flying long distances on migratory routes. “It’s the waterfowl – which are ducks, swans and geese – that normally spread a highly pathogenic avian influenza. However, the waterfowl that originate in Asia, their flyways bypass Australia, which is why we’ve been spared some of the really bad outbreaks that other countries have had.”

Although an outbreak of an HPAI virus has never been detected among Australia’s wild birds, LPAI viruses are “part of the natural virus community of wild birds worldwide, including in Australia,” according to Wildlife Health Australia (WHA). The independent coordinating body reports almost all LPAI subtypes (H1-16, excluding H14) have been detected in Australian wild birds. LPAI viruses tend to be carried by wild birds with no apparent symptoms, and fatality from the virus has not been reported in Australia.

However, there are concerns native wildlife could be devastated if an HPAI virus outbreak were to occur in Australia, and with no way to prevent migratory birds from entering the continent, some researchers believe it will only be a matter of time before an outbreak will occur.

How concerning is H7N3?

Professor MacIntyre says the strain of bird flu detected in Victoria is highly infectious. “It’s highly pathogenic, which causes the birds to be very sick.”

“It’s a cause for concern because, obviously, any avian influenza outbreak in farmed poultry has an economic impact. Generally, you’ve got to cull the birds to control the outbreak, so there are significant losses for farmers, and of course, you don’t want it to spread,” says Professor MacIntyre.

“However, in the past, we’ve had about nine H7 outbreaks in poultry in Australia, and they’ve all been brought under control fairly quickly, usually through the culling of the birds.

“If it has got to the poultry, then yes, our native wildlife probably has been exposed to H7N3. There would have been exposure, but it hasn’t been apparent in the way that the H5N12.3.4.4B has been in the US and Europe. They’ve noticed wild animals dying.”

Past cases of HPAI virus in Australia

| YEAR | AVIAN INFLUENZA SUBTYPE | LOCATION |

|---|---|---|

| 1976 | H7N7 | Melbourne, VIC |

| 1985 | H7N7 | near Bendigo, VIC |

| 1992 | H7N3 | near Bendigo, VIC |

| 1994 | H7N3 | Brisbane, QLD |

| 1997 | H7N4 | near Tamworth, NSW |

| 2012 | H7N7 | near Maitland, NSW |

| 2013 | H7N2 | near Young, NSW |

| 2020 | H7N7 | near Ballarat, VIC |

“On each occasion, the outbreaks were quickly detected and eradicated, and only a small number of farms were affected. Effective eradication measures ensured that Australia has remained free of HPAI.”

– Agriculture Victoria

The rise of H5N1

A new HPAI virus that became known as H5N1 began concerning researchers when it was first detected in China’s southern Guangdong region in 1996. With a fatality rate in reported cases of 59 per cent, this highly infectious strain swiftly killed large numbers of birds across Asia before spreading through Europe, Africa, North and South America, and the Middle East. In less than three decades, it has caused a panzootic (the animal equivalent of a pandemic), while over half a billion poultry have been euthanased in an effort to prevent further spread of the virus.

Although it is impossible to calculate the true toll on wildlife due to the difficulties of monitoring, millions of fatalities have occurred globally. Around 650,000 wild birds have been reported dead in South America alone.

The H5N1 virus reached the Antarctica mainland in February, with scientists especially concerned for the continent’s vulnerable wildlife. It leaves Oceania (Australia and New Zealand) as the only remaining region unaffected by the strain.

“The clinical picture for H5N1 is really quite scary,” says Professor MacIntyre. “It’s more than just a severe respiratory infection, we’re seeing quite severe brain infection and effects on the neurological system in mammals and birds that are infected.”

Human transmission

H5N1 is known to have crossed the species barrier at least three times, with at least 26 species of mammals having been infected. Despite being first reported on Antarctica’s mainland less than three months ago, the virus has already been found in penguins, elephant seals and fur seals.

This also means transmission to humans is possible. In a separate incident to the H7N3 outbreak at the egg farm, Victorian authorities also announced yesterday the first confirmed human case of H5N1 avian influenza in Australia. The patient was a child who had travelled to India in March and acquired the infection. Clare Looker, Victoria’s Chief Health Officer, said it was unclear how the child had contracted the virus, although it was likely from coming into contact with infected poultry.

The World Health Organization has reported a total of 889 cases and 463 deaths from 2003 to 1 April 2024 from H5N1.

The H7N3, H7N7 and H9N2 avian influenza viruses are also known to have been transmitted to humans.

While most transmission of avian influenza occurs from birds to humans, mutations in the strains are leading to changes in how the virus works. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports nine states are struggling with H5N1 outbreaks among dairy cattle. However, it today reported a second case of transmission from cows to humans after the infection of a Michigan dairy worker.

“Scientists have gone and just tested the milk on the [US] supermarket shelves and found more than 30 per cent of the milk samples are contaminated with H5N1,” says Professor MacIntyre. “Pasteurisation should kill the virus, but there is quite a big trend in the US to drink raw milk. And of course, there’s also incidents where the milk is inadequately pasteurised.

“There’s also eating of meat, so eating a rare steak, for example, could be quite a risk. Once it gets into the food chain at that level, which it clearly is in the US, there’s a much greater risk of a mutation arising that becomes transmissible in humans.”

Australia’s safety measures

Australia has so far avoided an outbreak of the H5N1 strain. We know this due to a nationally coordinated surveillance system for avian influenza in wild birds, which includes monitoring long-distance migratory birds.

Between July 2005 and December 2022, over 135,000 wild birds were tested for influenza viruses across Australia. In 2022 and 2023 alone, researchers from WHA collected almost 1000 samples from recently arrived migratory birds without detecting the virus. Other routine testing of dead birds around Australia also found no trace of HPAI strains.

Australia has some of the world’s strictest biosecurity measures to protect against diseases entering the country through imported birds or poultry products.

These measures include screening incoming goods and passenger luggage with x-rays, inspections, and detector dogs at airports, seaports and mail centres.

Poultry producers also have monitoring systems that quickly detect disease in flocks, leading to veterinary investigations.

While there is no way to prevent H1N5 from entering the country through wild birds, Australia does have an emergency response plan for HPAI outbreaks.

The AUSVETPLAN Response Strategy for Avian Influenza outlines a nationally agreed approach to avian influenza outbreaks in Australia.

Australia’s response to avian influenza

Procedures for responding to outbreaks generally include:

- euthanasia of infected and in-contact poultry (depopulation)

- decontamination

- strict quarantine

- movement controls to prevent spread of infection

- tracing and surveillance to locate the extent of infection

Source: Agriculture Victoria

During the most recent outbreak in 2020 and early 2021, there were three different strains of avian influenza across three local government areas – three egg farms with HPAI H7N7, and two turkey farms and an emu farm with LPAI strains.

These outbreaks were controlled through the destruction of approximately 433,000 domestic birds, and continued surveillance of both domestic and wild birds.

There is currently no permitted treatment for infected birds due to the strict policy of eradication of HPAI and LPAI.

As of August 2020, one avian influenza (H5N2) vaccine is registered in Australia, and three other active constituents (H7N1, H5N9, H5N2) have been approved by the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA).

If any of these vaccines or active constituents were to be considered for use in the case of an Australia-wide HPAI outbreak, the APVMA would need to be consulted.

Any suspicion of an emergency animal disease (EAD) should be immediately reported to the 24-hour EAD Hotline on 1800 675 888 or to your local vet.