Even the most remote place on Earth is beginning to crumble as the planet’s warming woes continue.

When British Antarctic survey scientist Peter Fretwell spoke at the SCAR biology symposium in Christchurch, New Zealand, in July–August 2023, his words drew gasps of despair that later rippled around the world. SCAR – the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research – represents scientists working on research involving Earth’s great frozen southern continent. The Christchurch gathering was their first face-to-face conference since the COVID pandemic began. Peter, a cartographer renowned for monitoring wildlife at the planet’s remote poles by using high-resolution satellite imagery, was there to present some alarming news – evidence of catastrophic breeding failure in emperor penguins on the Antarctic Peninsula due to record low levels of sea ice.

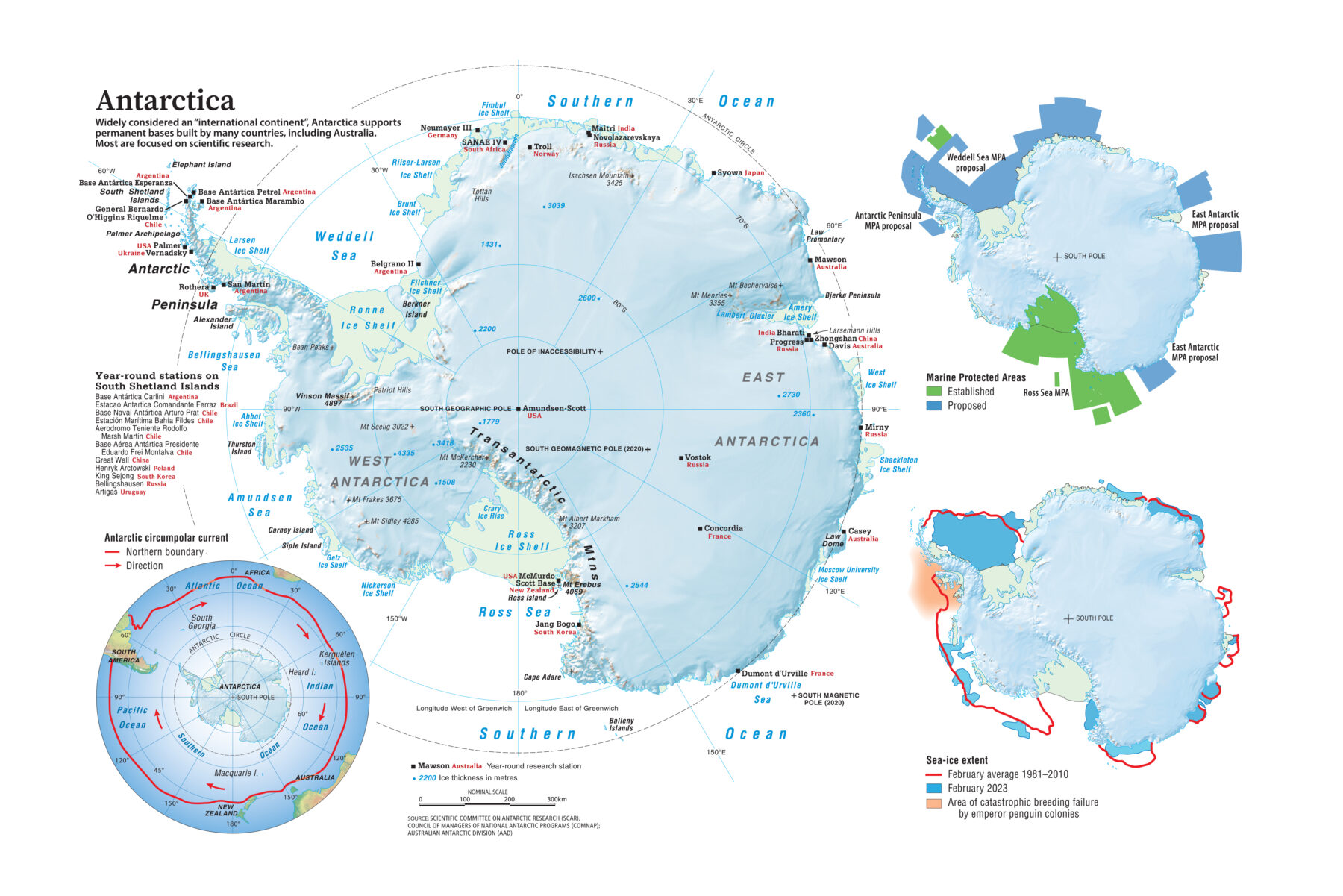

Sea ice is frozen sea water, and it forms, metres deep, around Antarctica each winter. It floats on top of the ocean, clinging to the continent’s edge while stretching across the water for many kilometres. It retreats in summer, although never completely, and its seasonal fluctuations influence the global climate. It also profoundly and directly affects the Antarctic environment, where it influences ocean circulation, weather and the local climate. The rhythmic coming and going of sea ice is critical to all Antarctic life, from crabeater, Weddell and leopard seals, to humpback whales, Adélie and chinstrap penguins, and Antarctic skuas. But it’s particularly important to emperor penguins because it’s the place where most of them breed.

In the depths of winter, when the sea ice is at its greatest, these penguins congregate in their hundreds or thousands in noisy colonies, buffeted by the coldest and strongest winds on the planet. Here they find partners, court, mate, and produce no more than one chick per pair each year. The fluffy down of the chicks isn’t waterproof, but the sleek plumage of adult penguins is, allowing them to ‘fly’ at extraordinary speeds with great agility through freezing waters, hunting prey such as fish and the tiny prawn-like crustaceans called krill. About 60 emperor colonies form on Antarctic sea ice every year.

The extreme remoteness and conditions mean satellite imagery is often the only way of locating these colonies and estimating emperor numbers. “Peter got up [at the SCAR meeting] and put up these satellite images [from the 2022 winter] and said, ‘Well, this colony went, and this colony, and this one’,” recalls Professor Dana Bergstrom, the former lead of Biodiversity Conservation with the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD), who was in attendance to deliver a keynote address. “The whole room was stricken, and our hearts just sank collectively.”

Everyone knew what the distant imagery would have meant for penguin life at sea level. And that, says Dr Barbara Wienecke, a seabird ecologist with AAD and one of the world’s leading emperor penguin experts, would have been fluffy chicks tumbling en masse into the water. “They wouldn’t have had any chance of surviving,” she says. “Their breeding platform didn’t exist anymore. This event happened when the chicks were not yet waterproof, so when they fell into the water, they might have been able to swim but their plumage would have got waterlogged and they all would have died – thousands of them – of hypothermia.”

The grim observations made by Peter and his team were published weeks later in the Nature journal Communications Earth & Environment, bringing them to the world’s attention. The despair they generated at the Christchurch conference spread across the planet – notably in the Northern Hemisphere, which only has the Galápagos penguin, just north of the Equator – indicating the global appeal of these seabirds.

“Our addiction to fossil fuels is killing baby penguins,” lamented The Japan Times.

“Shocking! Low ice levels leads to the death of thousands of emperor penguin chicks,” cried The Times of India.

“Record sea-ice melt in Antarctica doomed thousands of penguin chicks to a watery grave,” wailed the Los Angeles Times.

There have been isolated reports of emperor penguin colonies collapsing during the past decade: the notoriously dynamic and ever-changing Antarctic environment is, after all, one of the toughest places in which to survive on the planet. So this hardy seabird species has probably been dealing with colony losses for millennia. But the total collapse of so many colonies at one time that was documented by Peter seems unprecedented. It was the most confronting of many accounts of recent change in Antarctica presented at the 2023 SCAR conference, and it prompted the drafting of the “Christchurch Communique”. That document, signed by hundreds of scientists from 20 different countries, called for urgent and immediate action to stem what’s occurring at Earth’s remote, most southerly region.

“Antarctica,” it begins, “is currently experiencing dramatic changes at unprecedented rates, marked by repeated extreme events. These include circum-Antarctic heatwaves and an autumn heatwave last year [2022], with temperatures soaring up to 40ºC above the average…both last summer and this winter, sea-ice extent has reached record lows. These changes have happened even faster than scientists predicted.

“This,” the SCAR scientists warned the world as they delivered the communique, “is a critical moment, impacting our wellbeing, future generations and ecosystems globally. Confronted by this evidence, we urgently call on nations to intensify and exceed their current commitments to greenhouse gas emissions reductions.”

Ringing alarm bells

It’s not as if the current situation in Antarctica hasn’t been predicted. The continent has been like the proverbial canary in the coalmine for more than the past decade, making alarm chirps that have seen the world’s climate scientists becoming increasingly concerned.

When it comes to metaphors though, it now seems the canary is close to falling off its perch. Dana is a member of a growing group that now likens Antarctica to a charging grey rhino. It’s been poked and prodded so much that it’s not just showing warning signs, but has turned around to rage right back at the rest of the planet.

Antarctica might be many thousands of kilometres from most countries, but it affects us all like none of the other six continents do. What happens in Antarctica doesn’t stay in Antarctica.

Most significantly, the continent is a key driver of the planet’s climate. A warming of waters around the continent in the Southern Ocean, for example, will slow ocean circulation globally and can drive extreme weather events, not only in its neighbouring continent of Australia, but also at the planet’s other end. Likewise, melting Antarctic ice will raise sea levels globally. And we’re not talking now about sea ice, but the massive Antarctic ice sheet that covers the continent.

At 14 million square kilometres in area and holding some 30 million cubic kilometres of fresh water – 30 per cent of the planet’s fresh water – it’s easy to comprehend how the melting of this massive ice block, Earth’s largest, would raise sea levels globally. And that’s exactly what appears to be happening.

The dynamics of this huge chunk of ice are complex. It grows with each winter snowfall and diminishes with summer melts. But surveys have now confirmed that the amount of bulk it’s losing outweighs the snowfall that replenishes it. Put simply, the Antarctic ice sheet is becoming thinner, and has been for several decades. The upshot of that, of course, is rising sea levels – globally.

Melting ice issues

Undoubtably caused by the melting of the Antarctic ice sheet is another worrying phenomenon that’s recently been documented by a team led by Dr Kathy Gunn, an oceanographer and climate scientist with CSIRO. In a landmark paper published in May 2023, in Nature Climate Change, Kathy and her team reported that the circulation of what’s known as Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW) has slowed down significantly, “by as much as 30 per cent since the 1990s,” Kathy says. “This slowdown locks in decades of impacts.”

What’s the significance of this? AABW is rich in oxygen and very salty, which makes it dense and heavy. There’s a massive amount of it – about 250 trillion tonnes – and it sinks through the ocean near Antarctica each year. This sinking process ultimately drives ocean currents worldwide. In this way, AABW acts like a lung, breathing oxygen and nutrients deep into all the oceans – the Indian, Pacific and Atlantic – because, of course, all the world’s oceans are connected.

What’s thought to be happening is that the meltwater coming off the Antarctic ice sheet, which is fresh water, is effectively diluting, deoxygenating and lightening AABW so it’s sinking more slowly. This slowdown of AABW circulation will starve the deep ocean everywhere of oxygen and nutrients. No-one is sure what the flow-on effects will be in the upper ocean and on land. But, bearing in mind that it’s such a fundamental physical process of the planet, the consequences are likely to be huge. This AABW circulation slowdown had been predicted by scientists. But what we’re seeing now wasn’t expected to happen for decades, until 2050.

Problems with the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) are also potent signs that things are not as they should be on the southern continent. This is the fastest-moving current in the world and it wraps around Antarctica like a strong, broad pressure bandage, extending from the surface of the ocean to the bottom. It’s created by strong westerly winds across the Southern Ocean, combined with the impact created by the difference in water surface temperature between the Equator and the South Pole.

The ACC keeps Antarctica frozen by locking in the icy water that circulates around the continent and keeping out warm water. But the mechanism is leaking. At the time of going to press, CSIRO’s massive oceangoing deep-sea research vessel RV Investigator (see Delivered from the deep, AG 175) was heading south with a team of oceanographers and climate scientists to try to understand what exactly is going on with the ACC, and why it’s happening.

The return of the ozone hole

The environmental assault on Antarctica, which the continent is now redirecting back at the rest of the planet, isn’t only coming from the waters that surround it, but also from overhead. High up in the sky, the hole in the ozone layer has returned.

When this potentially catastrophic ‘tear’ in the planet’s stratosphere, more than 10km above Antarctica, was discovered by scientists in 1985, it quickly set global alarm bells ringing.

Ozone is a gas that forms a kind of atmospheric ‘blanket’ around Earth to keep out much of the sun’s UV radiation. Without it, life as we know it would never have evolved on this planet. The hole over Antarctica quickly became recognised as the most extreme sign of a phenomenon scientists began finding evidence for, worldwide, during the 1980s: stratospheric ozone was being destroyed across the planet by human-produced gaseous chemicals, notably chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which were used as propellants in aerosols and as highly effective refrigerants in refrigerators and air conditioners. It was feared the destruction of Earth’s ozone layer would mean we’d be bombarded during the 21st century by such high levels of cancer-causing UV radiation that life outdoors would be almost impossible for our species – and, of course, for most other species on the planet.

But just as it seemed that humans had done irreversible damage to the planet’s atmosphere, there were signs the hole was slowly healing, due to the gradual phasing out of CFCs after the introduction of the international treaty known as the Montreal Protocol. Early this decade, scientists finally confirmed that long-term recovery of the hole was underway. It was hailed as one of humanity’s greatest environmental success stories, and showed what could be done with a unified global geopolitical effort.

Now, however, new research led by an atmospheric scientist at New Zealand’s University of Otago, Hannah Kessenich, reports that the ozone hole is again increasing in size and it’s unlikely to be because of CFC use. “The past three years (2020–2022) have witnessed the re-emergence of large, long-lived ozone holes over Antarctica,” Hannah’s team reported in November 2023 in the journal Nature Communications. “The recent deep and long-lived ozone holes have already resulted in extreme UV levels over Antarctica,” the paper explained. “Beyond local UV effects, Antarctic ozone is intrinsically linked to the climate and dynamics of the Southern Hemisphere; changes in stratospheric ozone levels drive circulation changes across the entire hemisphere…”

An issue of geopolitics

All these problems besetting the Antarctic continent could be slowed down – even eventually halted – with a global reduction in carbon emissions. Prevent what’s causing climate change and you’ll slow the charge of Antarctica’s proverbial rhino, although much change is already locked in.

But that’s a geopolitical decision that’s beyond the scope of the public servants and scientists who both manage, and try to protect, Antarctic ecosystems. In the meantime, there are things that can be, and are being, done on the ground in Antarctica.

Despite all these large, threatening processes, much of Antarctica remains free from human impact. “Most of the continent is untouched, primarily due to its remoteness and because it’s covered in ice,” says Queensland University of Technology’s Dr Justine Shaw, a conservation scientist and Antarctic ecologist, who’s worked extensively during the past two decades with the Antarctic science programs of both South Africa and Australia. “Most of the continent is still wilderness and the world needs to understand that’s what we’re impacting in Antarctica – a wilderness. There’s no mining, no agriculture, no cities, and yet it’s still vulnerable – on a massive scale – to all these global threats. That vulnerability is a really powerful story for the world to hear.”

Like many scientists working in the Antarctic, Justine thinks protected areas are one of the most important local management tools presently available for the conservation of the continent’s wildlife. Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are particularly valuable, because most Antarctic wildlife are connected to the sea for most, if not all, of their lives.

Major decisions about managing Antarctica tend to be protracted, multilateral processes. That’s because they need to proceed within the terms of the Antarctic Treaty, which was enacted near the end of the Cold War and set the continent aside for peace and science.

The treaty came into effect in 1961, after being signed in 1959 by the 12 countries whose scientists had, at that time, been active in and around Antarctica. This included Australia and six other countries that have territorial claims. Since then, 44 other countries have agreed to the treaty, but only 29, including Australia, are Consultative Parties that can make decisions about the continent – including what areas deserve special protection.

Declaring an MPA in Antarctica is always potentially controversial, mostly because of lucrative fishing interests and because consensus among all parties is required. Antarctica’s first was the South Orkney Islands Southern Shelf MPA, established in 2009, followed by the massive Ross Sea region MPA in 2016, which took 10 years of negotiations to get over the line. Three proposals currently under consideration would protect areas of the East Antarctic, Weddell Sea and Antarctic Peninsula.

“Through these large areas we’re protecting entire ecosystems, and all the processes and species that occur within them,” Justine says. “And there are spill-over benefits to the waters surrounding and beyond protected area boundaries.”

All of Antarctica is protected under the treaty, but, she says, more could be done on land to identify and protect at-risk areas with unique values. Antarctica doesn’t have national parks, but it does have 75 sites that are Antarctic Specially Protected Areas, managed in different areas by different governments.

But more could be done to protect the environments, ecosystems and species, Justine adds. “Most of the biodiversity on land is restricted to the ice-free areas,” she says. “Not much of Antarctica is ice-free, so there are tiny [pockets] of ice-free land…that are really valuable, because that’s where everything is.”

Bird flu: an existential crisis

The one threat that presently has everyone with an interest in Antarctic wildlife on tenterhooks is bird flu. This pathogen, also known as avian influenza, has been around for decades. But a new highly pathogenic and contagious strain – HPAI H5N1 – has emerged. And it’s not just infecting and killing birds en masse, it’s jumped into mammals and is having the same devastating impact.

Scientists have been tracking its spread down the west coast of South America for several months. At the time of going to press, it had reached South Georgia, a subantarctic island just north of the Antarctic mainland, where it was recorded in Antarctic skuas and southern elephant seals.

“Bird flu is absolutely terrifying because it’s so deadly and it doesn’t just affect birds,” Dana says.

Everyone is now bracing for its arrival in Antarctica this summer and reluctantly, but realistically, anticipating a massive loss of life among wildlife. “All the seabird researchers are feeling like an existential crisis is bearing down on us and our study ecosystems,” says AAD seabird ecologist Dr Louise Emmerson. “We’re all incredibly attached to our study species, and it feels horrendous that there’s very little we can do apart from monitor the impacts, avoid spreading it [bird flu] further, and maintain the resilience of the wildlife through other management actions.”

Emily Grilly, WWF-Australia’s Antarctic conservation manager, agrees this upcoming summer in Antarctica is likely to be devastating for wildlife because of bird flu. “I think we’re going to see some haunting images,” she says. “And it’s the last thing that Antarctic wildlife needs right now, when it’s trying to adapt to this changing climate.”

Hope for the wilderness at the bottom of the planet

Despite all the despair, there’s an overwhelming feeling of hope among the experts that Antarctic wildlife will be able to adapt and survive. It has, after all, been adapting and surviving for millennia in one of the most volatile and harsh environments on the planet. But it’s the rapid pace of change that has scientists worried. The answer to that, most Antarctic experts agree, lies in the hands of everyday people worldwide. And they’ve been buoyed by the empathetic way the world responded to the mass death of emperor penguin chicks.

Dana, who is now mainly affiliated with the University of Wollongong, recently launched the Pure Antarctica Foundation, a not-for-profit that draws attention to the wonders of Antarctica and the human-induced perils it’s now facing. The foundation is planning to connect with the grief the world showed for the emperor penguin chicks by staging a worldwide Penguin Vigil.

“I want people to come together and express their sadness,” she says. The vigil is planned to begin in Sydney on the winter solstice – 21 June – and then spread around the globe. The timing of the vigil will coincide with the period when emperors begin arriving in Antarctica to form their breeding colonies.

“Yes, it’s a tough time for the wildlife in Antarctica at the moment,” Louise agrees. “They’ve got avian influenza bearing down on them, they’ve got fisheries expanding, they’ve got climate change – and the unknown impacts from that on the food web they rely on. I mean, Antarctic wildlife is incredibly good at responding to environmental change – they’ve been doing it for many thousands of years, and that’s why they are there. But when we keep pushing them over the edge, there’s a limit to how much they can respond or adapt to.

“I’m still trying to be as optimistic as I can, that there’s something we can do, but the signals are alarming. Now is a critical time for us to pull out of our back pocket whatever we can to help support that ecosystem. I believe we have a moral responsibility to do that.”

Justine says it’s vital people understand that, as far away as Antarctica seems, whatever they can do to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions in their own backyards will help.

“If you explain that to people and ask if they hope their grandchildren get to live with penguins in their lives, I see them respond,” she says. “And I ask, ‘Do you want your grandchildren to know that there is a wilderness at the bottom of the planet, where whales come every summer to feed, and there are leopard seals and all these amazing animals?’”

And most people, she says, reply with an emphatic, “Yes.”