IN 22 AUGUST 1770, the crew of HMB Endeavour, led by Lieutenant James Cook, reached Possession Island, off the northern tip of Australia.

From there they sailed west to the Dutch colony of Batavia for repairs, before making the long journey home. Cook’s time in Australia was over, and although he would lead two more voyages of discovery, Endeavour was in a woeful state and no longer suitable to meet the rigours of such journeys.

Endeavour’s stint in Australia is well documented, but what is less known is what happened after its return to England. A surprising chain of events saw it caught up in the 1775–1783 American War of Independence, and it eventually ended up on the murky sea floor of a historic harbour in Rhode Island, USA, where what remains of it still resides.

Between 1771 and 1774, the Royal Navy used Endeavour to shuttle goods and troops to the British garrison on the Falkland Islands, off Argentina. But in 1775, after the battered vessel was sold to private owner James Mather for £645, it disappeared from naval records, confounding historians.

The story long believed to be true was that Endeavour was renamed La Liberté and that it arrived in Rhode Island in 1793 as part of a French whaling fleet. The remnants of La Liberté disappeared long ago beneath land reclaimed as a parking lot, but its stern post, thought to be that of Endeavour, arrived in Australia for the bicentenary in 1988. It remains on display at the Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM).

In 1997, however, Australian amateur historians Des Liddy and Mike Connell uncovered clues in a shipping register that Endeavour was, in fact, renamed Lord Sandwich and that La Liberté was actually HMS Resolution, which Cook sailed on his second and third voyages.

Subsequent sleuthing through historic records by experts including Dr Kathy Abbass, director of the Rhode Island Marine Archaeology Project (RIMAP), has painted a remarkable picture of Endeavour’s final years as Lord Sandwich, including its role as a troop transport, shipping German Hessian mercenaries who hailed from the southern German province of Hesse-Cassel, to America to fight for the British.

By August 1778, she was being used as a prison hulk holding American revolutionaries in Rhode Island’s Newport Harbour. The French had by then entered the war on the side of the Americans, and with a fleet of their warships poised to take Newport, Lord Sandwich was among 13 vessels deliberately sunk in formation by the British to block access to the harbour.

It’s now 240 YEARS LATER, and on an unseasonably warm October day in 2018, Kathy Abbass perches on a chair on the waterfront of Newport’s Goat Island. She looks out at buoys bobbing in the wide, grey expanse of the harbour. A suspension bridge stretches across Narragansett Bay behind her.

“When the British knew the French were coming, they told the navy vessels to destroy themselves,” says Kathy, who is at once knowledgeable and formidable.

“Thirteen were sunk in a line here on the west side of Goat Island,” she adds, gesturing towards the buoys that mark RIMAP’s dive sites and the five wrecked vessels thought to include Lord Sandwich (formerly Endeavour).

There are more than 230 historic wrecks in this important colonial harbour. Kathy formed RIMAP in 1993 to study some of the wrecks of those involved in the American Revolution. She was not seeking Endeavour – in fact, as an American, it was barely on her radar.

But once the Australian enthusiasts presented her with the first clue that Endeavour might lie among the 13 vessels RIMAP was investigating, she pulled together a small amount of money to get to London. There, she found the chain of evidence to prove that Lord Sandwich was the same vessel that had been around the world with Cook in 1768–71.

“I didn’t stand up in the reading room of the Public Records Office and scream ‘I found it!’, because you don’t do that, but it was exciting,” she says.

“How many people in their career overturn an idea that has been around for 170 years?”

In the 18th century it was very common to rename vessels, as Mather did with Endeavour after he purchased it. Indeed, that was the second time the vessel had been renamed – its life began in 1764 in Whitby, Yorkshire, as the Earl of Pembroke, where it toiled as a collier transporting coal.

Both Kathy and Kevin Sumption, the director of Sydney’s ANMM, believe the later renaming was to curry favour with John Montagu, the fourth Earl of Sandwich, who was Britain’s First Lord of the Admiralty and a patron of Cook’s voyages.

“It was a ploy to take a vessel in very poorly condition and play on the pride and ego of Lord Sandwich himself,” Kevin says. After the outbreak of war in the American colonies in 1775, the British government was desperate for civilian ships to help it transport troops to quash the rebellion. Endeavour was tendered for consideration but initially rejected.

“The guy who sent Cook around the world was the fourth Earl, so I’ve always assumed it was renamed Lord Sandwich sucking up to him,” Kathy says.

Whether it was that or the repairs that eventually swung it, the ship was accepted for service in February 1776 and three months later was carrying more than 200 Hessians on a crossing to the Americas.

There are several reasons why this information was lost in the mists of time. For a start, when Lord Sandwich arrived in Rhode Island, people may have had no idea it was the vessel that had sailed to Australia – the 18th-century equivalent of having flown to the Moon. Things were valued differently then. “It was more of the cult of the individual,” Kevin says. “It was, in fact, [botanist] Joseph Banks who was lauded on their return and Cook’s fame comes a little later. The ship itself was more incidental.”

The fact significant ships sometimes dropped into obscurity, combined with confusion made by frequent renaming, creates a mess for modern historians to unravel. “It becomes a bit of a melange of stories that researchers must pick apart, using archival evidence and first accounts, to get to something like a truth – rather than just trading on the mythologies,” Kevin says.

In this case, the research proved that the stern post on display at the ANMM was not that of Endeavour, but instead belonged to Resolution. “This taught us to meticulously research and not to be so gung-ho as to make claims that won’t stand up to testing,” Kevin says, explaining that it is exactly that careful approach that RIMAP and the ANMM are now taking with a wreck off Goat Island that they increasingly suspect is Endeavour.

Since 1999 the ANMM has been an enthusiastic supporter of Kathy’s research, in the past five years helping RIMAP with archival work and providing a grant that supports dives on the wreck sites each summer. The museum’s maritime archaeologists also now fly from Sydney to participate in the dives.

After establishing RIMAP, but before finding evidence that Lord Sandwich was Endeavour, Kathy says she’d had a crisis of confidence. “About five to six years in, I started to think ‘this isn’t generating money, it doesn’t pay a living wage, why am I doing this?’” But finding the documents in 1999 that proved

Endeavour was in Newport and might be found made her persevere. That was 20 years ago. For 16 years, they did work to pick away at which of the 13 might be Endeavour, but progress was slow – dives are restricted to short summer seasons and RIMAP is a volunteer organisation that scrapes by on small grants and donations.

“We are coming closer to saying we’ve found it, but we still have to prove it,” Kathy says. Improvements in technology – such as remote sensing and photogrammetry, which have been used to stitch together thousands of photos to create detailed 3D reconstructions of wreck sites – helped, and by 2016 they’d mapped out eight of the 13 wreck sites.

That’s when they had an incredible stroke of luck that helped narrow their search. In the 1700s, it was standard after a scuttling for a surveyor to record the precise locations of where ships went down. In 2016 the ANMM’s head of research,

Dr Nigel Erskine, was scouring historic records at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London, when he found just such a report. It was critical in identifying the position of Lord Sandwich as being among a group of five of the 13 vessels to the north-west of Goat Island.

“That particular document was very important because it had names of the vessels and where they were sunk,” Kathy says. “It eliminated eight of the others and allowed us to focus on the five in the area where we know Lord Sandwich was put down.”

Within this group, they suspected HMB Endeavour, a 368-tonne vessel, was likely to be at least a third bigger than any of the other transports. “So, if we can find everything in this study area, and say which is the biggest, then that’s likely to be Endeavour,” Kathy says.

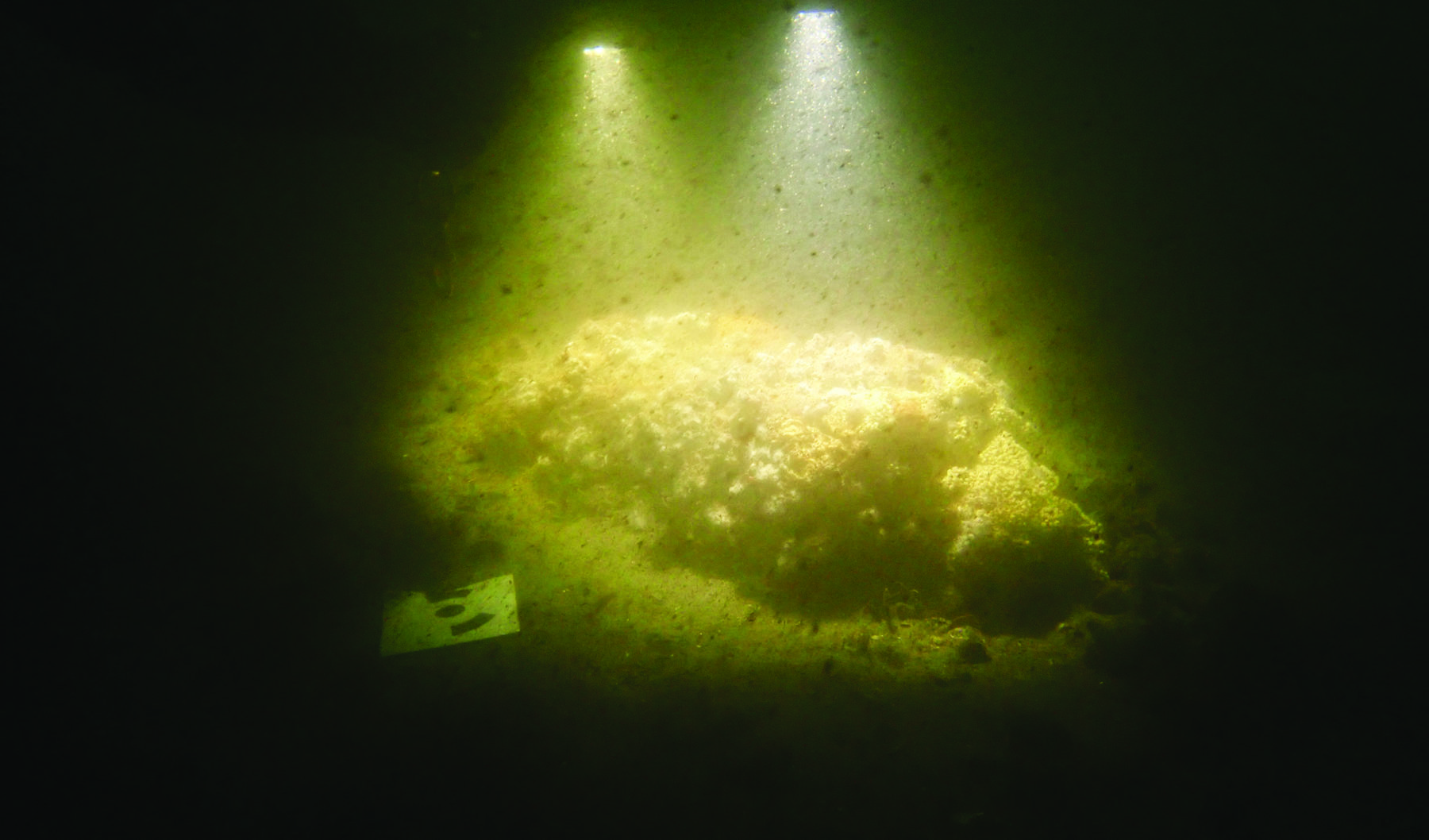

In 2018 the RIMAP and ANMM teams spent a week diving a promising site dubbed RI 2394 that they believe might be the wreck of the largest of the five vessels. But diving here, studying, and even just finding the wrecks, is difficult because visibility is poor and most of what remains of the 240-year-old wrecks is buried beneath the muddy seabed.

“It doesn’t look like much at all,” says ANMM maritime archaeologist and curator Dr James Hunter. “It doesn’t look anything like a ship. The average punter would swim right by.”

Unlike the gin-clear waters of the Caribbean or Coral seas, they’re lucky to see further than 2m in Newport, but James loves working there, nonetheless.

“Any day I get to dive on a shipwreck is a good day,” he says. “Every wreck has its own unique challenges and this one is no different – it’s a bit dark, a bit chilly, a bit deeper than many others, but very exciting.”

Cannons covered in dense marine growth and mineral concretions are the only thing that might hint at a shipwreck to the casual observer, and they are what led to the discovery of RI 2394 and then its mapping in 2007. But if you get a little bit deeper, buried in the silty mud, in an environment starved of oxygen, are the remains of the hull structure, consisting of perhaps 10–20 per cent of the original ship.

Because visibility is poor, photogrammetry has been critical as it allows the team to create digital models of the site that reveal the whole picture, allowing them to find clues to beams and other details of the ship’s structure. “When you get a model like that you can pull back and see the whole thing… It was a eureka moment,” says James.

Despite the fact the ANMM would dearly like to find

evidence that this wreck is Endeavour during 2020 – to coincide with events marking 250 years since Cook arrived in Australia – there’s no guarantee yet they have the right ship.

“What we’re dealing with is what we can see above the surface of the silt. So we chose the largest wreck that was exposed the most, that had timbers on it, that had some cannons exposed,” says Kevin. “But the next site over could be the same size or more covered over… There are all sorts of ways this might work out.”

Kathy is often asked if the plan is to raise the wreck, but this is very unlikely. “Raising vessels is very expensive and is inappropriate. UNESCO says that’s not the best use of a shipwreck anyway,” she explains, adding that a complete excavation is not needed to prove this is Endeavour, and would expose it to oxygen and marine life that would degrade it.

“Our approach is to just open it up enough to get the data we need and take care of the artefacts that are there,” she says. Leaving at least half the wreck undisturbed also means that, in the future, archaeologists with better technology and better knowledge can come back and make discoveries that wouldn’t be possible today.

Instead, the plan is to find a variety of clues indicating that this is Endeavour – but the chance of her still containing any artefacts associated with Cook is very low. “Our assumption is that it is the later uses of the vessel as the Lord Sandwich – the transport, her involvement in the Revolutionary War, holding prisoners onboard – that are most likely to provide the evidence,” Kathy explains. “And if we can prove we have the Lord Sandwich, then we know we have Endeavour.” Some of these things might be artefacts from her time as a prison hulk or even inscriptions scratched into the walls by known American revolutionaries detained on board. “You’re hoping to find something like this, but it’s a long bow to draw,” Kevin says.

A series of dives in September 2019 started excavations, revealing part of the ship’s structure and making some interesting discoveries. These included traces of leather, textiles, glass, ceramics, coal and ballast, as well as “a gunflint fragment and a fragment of a kaolin pipe stem manufactured between 1750 and 1800,” says Dr Kerry Lynch, an archaeologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and RIMAP’s field director.

While none provided a link to Cook’s vessel, “these artefacts are diagnostic to the time period Lord Sandwich was scuttled and help associate this wreck to the transport fleet,” she says. Some of the artefacts are now at RIMAP’s lab at the Herreshoff Marine Museum in Bristol, Rhode Island, where they are being conserved and studied further.

Another “marvellous and unexpected” find was the scuttling hole that had been punched through the outer hull, proving the vessel was one of the transport fleet that had been deliberately sunk. “Since our excavation unit was only three feet wide, and the remainder of the vessel is currently unexcavated, this was an extraordinary stroke of luck,” Kerry says.

Other ways Endeavour might be confirmed include finding repairs that match what was done to her either after her grounding in the Great Barrier Reef or in later refits, or finding unique quirks of her design, such as an unusual keelson structure that was added to vessels built at Whitby.

The wood used in Whitby is also very likely to have been distinct from that used in shipbuilding yards in North America, where some of the other scuttled vessels are believed to have been built.

“We are trying to combine forensics, photogrammetry and material culture [historic artefacts] with archival research, to have a web of evidence that, when you put it all together, there’s just no way it could be anything other than Endeavour,” Kevin says.

As Australian Geographic goes to press, the team has dives planned in early 2020, which it is hopeful might turn up further elements of this mesh of proof.

Even if RI 2394 proves not to be HMB Endeavour, Cook’s vessel is still almost certainly one of the five wrecks near Goat Island. Even just the prospect that they are working on “one of the most famous ships of all time” is a thrilling one, James says. “It’s almost like reaching back through time, to be able to touch that ship that witnessed so much.”

Revealing the untold story of this famous vessel has a special thrill. While everyone knows it as Cook’s HMB (His Majesty’s Bark) Endeavour, it had a series of other lives – it was a collier, Earl of Pembroke; a troop transport to the Falklands; and finally, Lord Sandwich, which played a part in the American Revolution.

“All of those aspects of that ship’s history are fascinating, and those are the things we know the least about,” James says.

At the time Endeavour arrived in Rhode Island, Newport was a major American port, with only Boston and Philadelphia being busier. Nevertheless, it’s incredible that both Endeavour and Resolution, “two of the most important exploration vessels of the Age of Enlightenment”, likely finished their careers there, Kevin says.

“Who would have thought that could be the case? That’s an amazing coincidence,” Kathy agrees. “People ask why would two of the vessels that sailed around the world with Cook end up in Newport Harbour. Well, that kind of coincidence happens in history a lot.”

Endeavour was scuttled on 4 August 1778 and Cook’s own demise followed just six months later, on 14 February 1779.

Following a dispute with islanders, he was stabbed to death on the beach at Hawaii’s Kealakekua Bay, where Resolution was moored for repairs. It was his death that would propel him, and the vessel in which he sailed to Australia, to fame.

“Cook was a nobody,” Kathy says. “He was a working-class guy who learnt all these skills as a navigator, cartographer and sailor. It wasn’t until his second and third voyage, and especially after he was killed, that he becomes the great icon.”

A decade later, in January 1788, the First Fleet arrived in Australia, an event that today has a complex and controversial legacy, much as Cook’s voyage does. Intriguingly, the British decision to colonise Australia was influenced by the loss of its 13 east-coast colonies in the Americas, where it was previously sending labour and prisoners.

“They’ve lost this strategic and economically important base in America and maybe it makes them start thinking about

Australia as an alternative,” Kevin argues. “So, there is an important connection to the American War of Independence.

“It’s a relatively unknown end for HMB Endeavour, but it’s also interesting for such a significant vessel to end up in an engagement so fundamental to the British decision to colonise Australia.”

This article was originally published in Issue 155 of Australian Geographic.