Mal Leyland’s life on the road

Mal Leyland is the winner of the 2019 Lifetime of Adventure award. Mal received this award on the 1 November at the Australian Geographic Society Awards.

Anyone over the age of 40 who grew up in Australia is likely to remember the Leyland brothers, the pair of tousle-haired adventurers who pioneered outback filmmaking through the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s. Together Mike and Mal Leyland – who were true brothers, Mike being older by three years – made more than 330 hours of Australian film and television. Their work included feature-length documentaries and television series and they became national treasures.

The brothers are best known for their weekly television show, Ask the Leyland Brothers, which aired from 1976 until 1984 and, at its peak, was watched by more than 2.5 million people. It saw the duo travel to far-flung places across Australia and New Zealand. The program’s premise was that people could write in and ask about “anything…as long as the answer is interesting”. The brothers would then chase the answer, usually to remote locations, and present their findings.

Each episode, after the show’s jaunty introductory tune that many Australians still hum, Mike and Mal would zoom off in dusty Kombi vans, taking us with them on their adventures into the wilds. They were bogged, stranded, and hit by storms and kangaroos. They fled fire and taught us how to follow animals to waterholes. They camped in trying conditions and made decent meals from scraps. Their cars rolled, their clothes deteriorated and their tempers flared. They took their families with them and taught us that exploring this country is a great way to have an adventure and that it can also be done simply and inexpensively.

The Leylands survived on diets of tinned food, good planning, logic and practical trouble-shooting. They held their cameras at arm’s length, exploiting the ‘selfie’ shot decades before it became fashionable and presented pieces in gales and from cliff edges. “When we were very young it was about challenging ourselves against the country,” says Mal, now 75 and still on the road. “As we got more mature it became the story of the people we met rather than our exploits.”

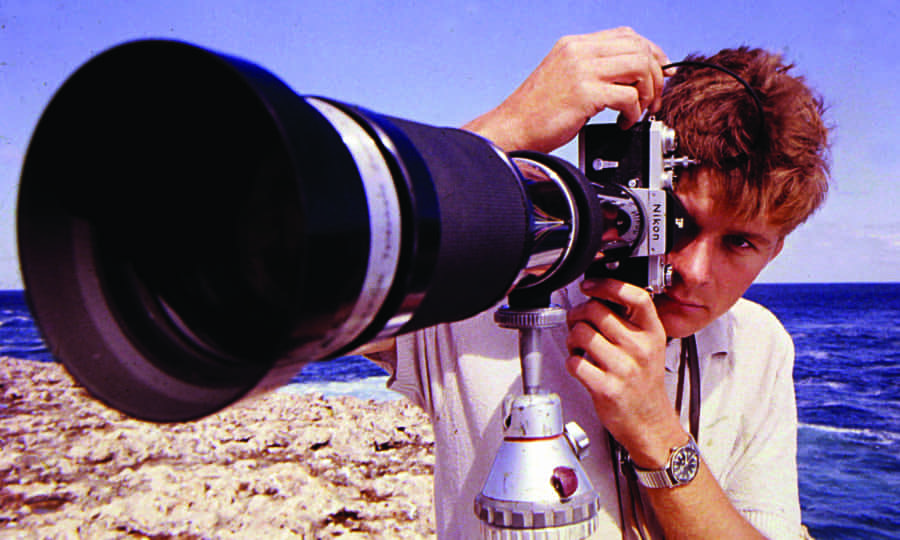

The Leylands, 1977.

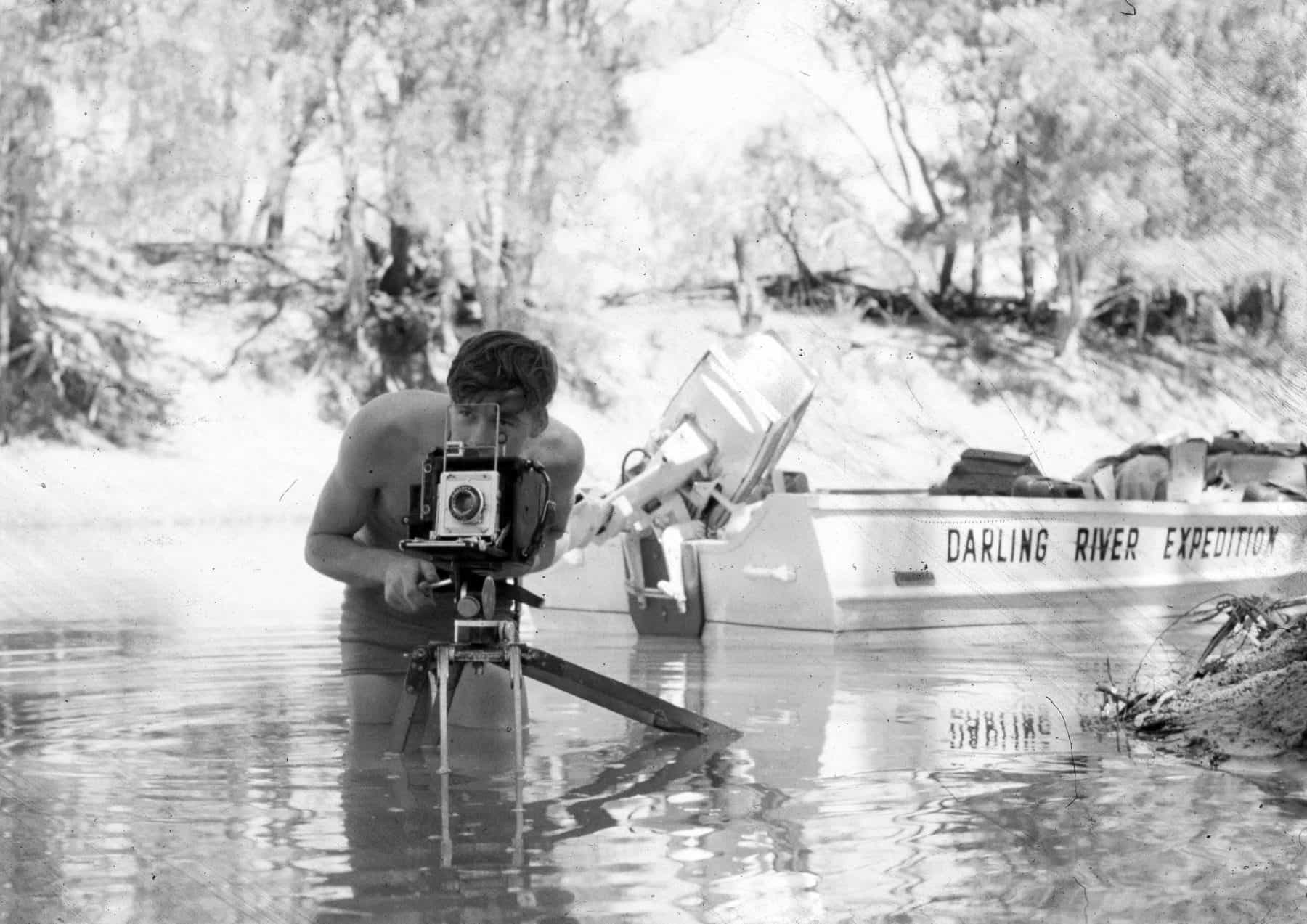

The Leyland’s on-screen journey began in 1956 when Mike, then aged 15, got a 16mm movie camera and the brothers filmed themselves and their friends as they explored outback New South Wales. They released their first documentary, Down the Darling, in 1963, when Mike was in his early 20s and Mal was in his late teens. The film covered their journey in a small aluminium boat as they travelled down the Darling River from Mungindi, in Queensland, to Mildura, in Victoria.

By the time Mal was in his early 20s, the brothers were ready to up the ante. They left their home in Newcastle, north of Sydney, and crossed the Nullarbor Plain. Then they drove north up the West Australian coastline and spent five days bush-bashing in four-wheel-drives through head-high scrub to reach Steep Point, mainland Australia’s most westerly outcrop. From there, they set off on a west–east crossing of Australia – a feat few people thought was achievable.

At Steep Point, they dropped a billycan from a cliff top into the Indian Ocean and hauled up a sample of the water from the west coast. They carried this with them for the next five months as they drove across about 5000km of often unmarked desert and wilderness, using a sextant to navigate. Mal says he was drawn to the merciless desert “as if wooed by a deadly damsel I could not refuse”.

After overcoming countless obstacles, including five smashed differentials, broken axles and impassable dirt tracks, they reached the other side of the country. At Australia’s most easterly point, Cape Byron, in northern NSW, they poured their pot of Indian Ocean into the Pacific. They had crossed the belly of Australia in as straight a line as possible. Mal says there were moments during the expedition when it felt entirely foolhardy. “I went for a walk into the Simpson Desert, losing sight of our camp,” he says. “It occurred to me that I may not survive, and I wrote a letter to my mum telling her I didn’t have any regrets.” It was 1966 and he’d just turned 21.

On their return to Newcastle, the brothers set up a makeshift editing suite in their basement and learnt on the job as they hand-spliced 16mm film, created soundscapes and added musical scores. The resulting documentary, Wheels Across a Wilderness, was released in 1967, and it was arguably their most successful.

For their next adventure Mike and Mal chose a high-risk sea expedition from Darwin to Sydney, retracing the voyage of Matthew Flinders. The 18 foot (5.5m) open boat they named Little Investigator offered very little protection from the sun or driving rain. Amid supplies of fuel, water and food, there was little room to move (or sleep) and as the bow hit each wave, it made a bone-crunching thump. “What a cocky, arrogant pair of smart-arses Mike and I were,” wrote Mal in his 2015 autobiography, Still Travelling. Plenty of people believed they wouldn’t survive to tell the tale.

Just days into the trip, Mal was electrocuted by the boat’s saturated starter motor, which sent a charge directly into his groin. He was still a virgin and considered the possibility that this might have rendered him impotent –excluding him from a range of adventures at the top of his bucket list.

Later, off the coast of Queensland, they struck enormous seas and Little Investigator was narrowly saved by a prawn trawler.

After six months, they spluttered into Sydney Harbour, completing what was then the world’s longest voyage in a small open boat. Importantly, they had enough footage to make their next documentary, Open Boat to Adventure.

Mal on the Darling River, 1963.

During the 1970s, Mike and Mal made another documentary, The Wet, which covered their journey to what is now Kakadu National Park, in the NT, and they began making television programs, including Off the Beaten Track and Trekabout.

In 1976 the siblings launched Ask the Leyland Brothers. They were joined by their wives and a growing gaggle of children. (Mal, it turns out, wasn’t impotent.) And they headed out in their signature Kombis at the directive of viewers, who keenly took up the brothers’ offer to “ask the Leylands”. The public sent them in search of things as diverse as lost monuments, rumoured migratory birds and ephemeral lakes. Each exploit was filmed and edited in the style of a home video.

For Mal, the series marked the point when the brothers shifted their camera’s gaze from their own stories of survival to the extraordinary characters they met along the way. Mal also began telling his own story of love and family. His wife, Laraine, travelled and worked alongside him. Each morning, they’d rise at dawn and drive to their filming location together. Each afternoon, they’d return to camp to clean the equipment, prepare the film for processing, write up their notes and arrange the next day’s filming. All this was with daughter Carmen toddling along beside them.

By this stage, the Leyland brothers had become national icons. Everywhere they travelled, punters were excited to be part of the Leyland adventure. Comedian Norman Gunston (aka Garry McDonald) described them as “the Starsky and Hutch of the dead centre”.

Like so many Australians, friend and fellow adventurer and founder of Australian Geographic Dick Smith was inspired by their spirit of adventure. “They did it all so inexpensively, spreading the message that anyone could do it,” he says. “They respected the landscape, were hard-working and earned their successes. Huge amounts of cash flowed in, making them very wealthy for a time and allowing them to pay off their homes as well as invest in properties.”

The brothers were ever conscious that the fickle television bubble might pop at any moment. As a safeguard they decided to spread their interests into hospitality and tourism, sinking their earnings into Leyland Brothers World, a bespoke theme park near Newcastle replete with its own replica of Uluru.

As interest rates soared during the early 1990s, it became the craziest Leyland adventure of all, and the most disastrous. Financial pressures tore the brothers apart and the bank foreclosed on the park. Both brothers exited penniless and resentful. After years of following in each other’s wheel ruts, they turned determinedly in different directions.

Mal, Laraine and Carmen.

Mal and Laraine scraped together what was left to build a new life in the NSW tablelands. Mal built a house by hand using discarded shipping containers. They became self-sufficient just as Mal was diagnosed with advanced bladder cancer. He believes the chemical-free life they created at their property, with its diet of fresh-picked produce, helped him defy the odds and beat the cancer.

Then in 2009, Mike’s second wife, Margie, told Mal his brother was close to death. When they met for the last time, Mike was a prisoner in an unresponsive body, atrophied by Parkinson’s disease. “How would you like to do one more trip, Mike?” Mal whispered in his ear. Despite having not uttered a word for days, Mike said, “One more,” and attempted a smile. Mike passed away soon after.

Laraine died in late 2018. After almost 50 years of marriage, so much of it spent coated in dust on unsealed roads, Mal is achingly conscious of the empty passenger seat.

He now travels in the relative luxury of a motorhome complete with solar panels, enough water to last him three weeks and a generator so he can edit his stories on the remotest of roads. At 75, he has started a new gig for Network 10 as a travel reporter, and would dearly love to work on another Leyland series with daughter Carmen.

True to his mantra that with only one life not a moment can be wasted, Mal is forging on. He hopes he might continue to inspire Australians to explore this remarkable continent, building their understanding of the land and sense of responsibility as it shifts uncomfortably in the next critical decades.

“Don’t delay,” he says. “Do it now. No-one enjoys the fact they’ve worked so hard they can buy a high-quality coffin.”