The moment has come. We’ve been eagerly anticipating it since arriving a week ago. We’re sitting in preassigned rows – bums on deck, with masks, snorkels and flippers at the ready – anxiously awaiting instructions from our crew as if this is the climax for a main event. Which it is. Then comes the call: “Go, go, go!” We hastily shuffle off the marlin board and dive into the deep blue waters of Ningaloo Reef.

Hearts are pumping and snorkels gurgling as we form an orderly queue to safely watch the rockstar of the reef take centre stage. It’s quiet and calm as we drift at the surface, then, out of the blue, the unmistakable silhouette of a whale shark, the world’s biggest fish, cruises into view. It’s like slow motion as we gaze in awe through our masks at this magnificent creature. Its white dots and stripes are a work of art highlighted in the sunlight rippling through the water. Using our long fins, we swim our hearts out to keep up for as long as we can. Unbothered by our presence, the shark continues cruising through the ocean, fading into the blue of Ningaloo, taking its hitchhiking remoras along for the ride.

Each year from March to July, the 300km-long Ningaloo Reef, about 1200km north of Perth off the West Australian coast, explodes with the promise of new life as its corals enter their reproductive cycle and release eggs and sperm en masse. This enormous simultaneous spawning provides a smorgasbord of food for swarms of zooplankton. In turn, the zooplankton attract hungry whale sharks in the largest aggregation anywhere in the world. Hundreds of this huge fish species arrive here to gorge on the plentiful but tiny zooplankton.

Whale sharks can grow to 18m in length, but most that visit Ningaloo are juvenile males in the 3–7m range. Still, a creature that size is an imposing presence in the water, particularly when it appears like a bus cruising towards you from the depths of the sea.

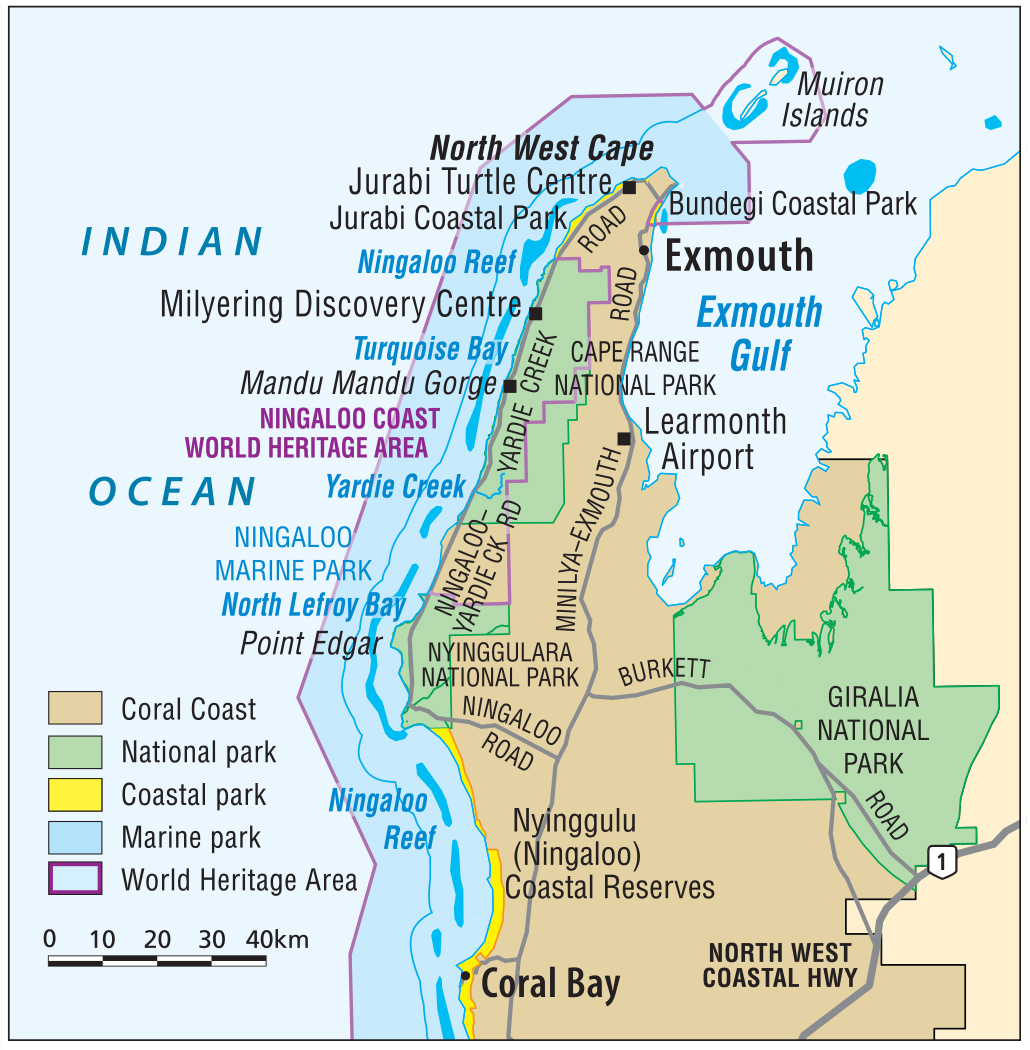

Our group of 10 is here as part of an Australian Geographic Travel tour exploring the 6045sq.km of marine and terrestrial environments of the Ningaloo Coast World Heritage Area, witnessing everything wonderful and wild that we can along the way. Our itinerary stretches from the Muiron Islands to the north, and to the west and east of Cape Range National Park, and this not only gives us the chance to explore the underwater wonders of Ningaloo Reef, but also offers a comprehensive list of the area’s other highlights, all done in style and at our own pace.

Our trip kicks off with a day exploring a secret gorge that’s home to a small population of endangered black-flanked rock-wallabies. It took quite a while to get there, however, because we are constantly stopping to check out the amazing birdlife spotted from our bus. With such a small group on this trip, we had the luxury of being able to take our time; we’re never rushed, and if we wanted to take a detour on a dirt road to track down a beach stone-curlew, we could! The relaxed pace let us take in the small things and soak up everything Ningaloo had to offer – our trusty guides, Martin Maderthaner and Scott Roberts, were always ready to share their extensive knowledge of the area’s flora and fauna.

Along the way, the twitchers among us ticked off the iconic wedge-tailed eagle, Australian bustard, white-bellied sea-eagle, osprey, brahminy kite, bar-tailed godwit, little eagle and more from our lists, and that was just on the first morning! It turns out to have been an early indicator of the vast range of biodiversity that we are to see, and it gives the sense that we’re in a truly wild, undisturbed place.

Eventually, we made it to the gorge and found what we’d come for. Black-flanked rock-wallabies are perfectly adapted to life on the steep canyon walls. They leap across rock towers, climb through cracks and hop up the sharply angled rock with ease. There is also a natural pecking order within the mob, with the perches highest up the cliff locked down by the more senior members.

There wasn’t much happening when we visited. Even though it was winter, the sun was baking the canyon and the wallabies were more interested in seeking shade to avoid the hottest part of the day. We made our way back out of the gorge past striking acacia, kurrajong and eucalypts, a beautiful contrast of green hues against the deep reds of the rock. All up, we managed to count 24 wallabies – information that will contribute to the ongoing surveys on the endangered population.

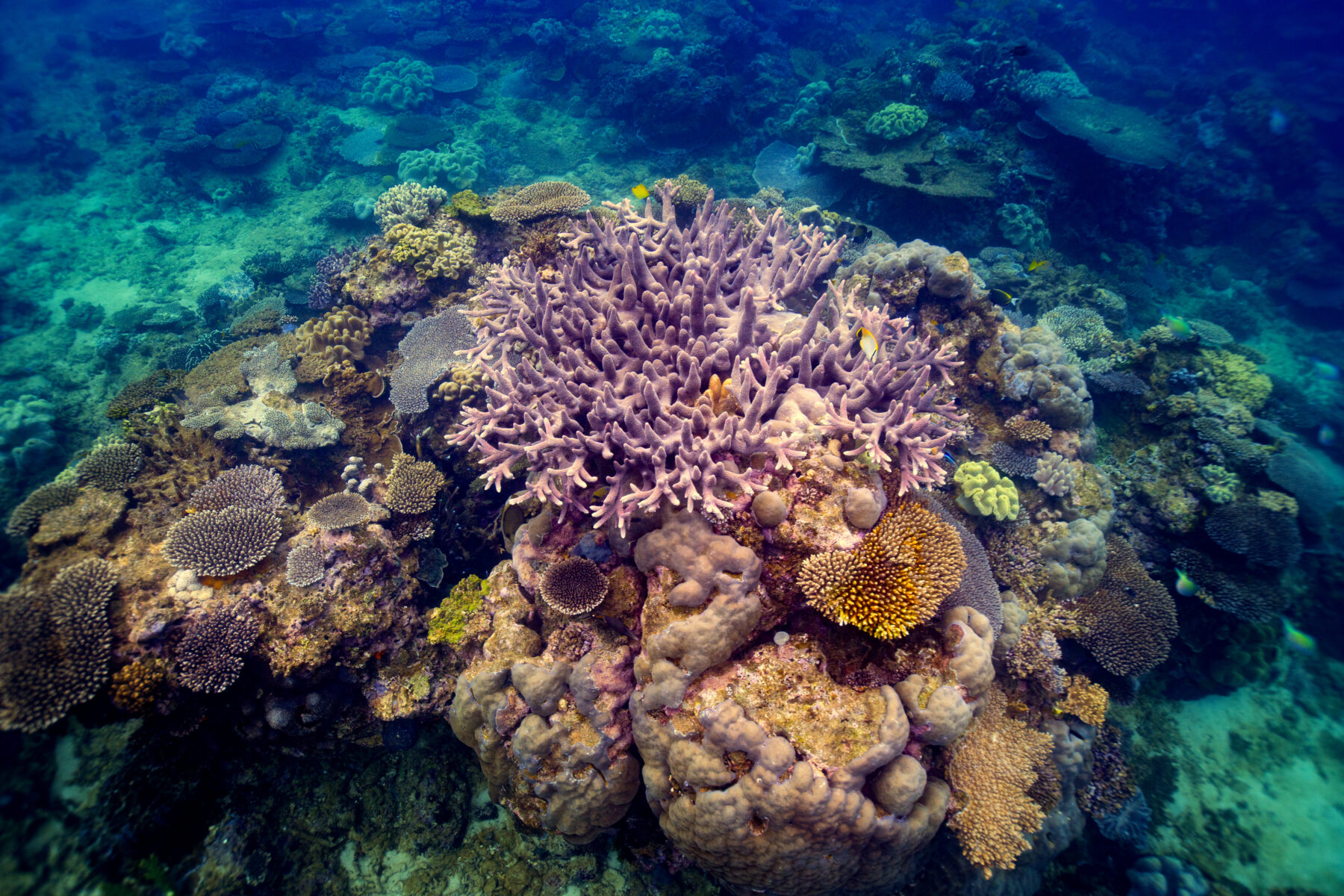

The contrasts in the Ningaloo area are spectacular: red Cape Range soils meet turquoise sea; flat coastal plains are cut by the canyons and gorges of the range; and a relative sparsity of wildlife on land gives way to a thriving kaleidoscope of life in the reef’s waters. And it was the reef we set off to explore next, departing early next day for a 30km cruise up the coast to the less-visited Muiron Islands. We anchored just off South Muiron Island, where the water is a deep clear turquoise and begging to be dived into.

We explored these waters for two days and were treated to some incredible snorkelling over shallow coral reefs. The diversity of hard and soft corals, other marine life and underwater landscapes provided a true sensory overload. We spotted green sea turtles, reef sharks, trumpet fish, bat fish, the endemic black sailfin catfish, a very chilled-out leopard shark, nudibranchs, sea snakes and so much more. We even managed a swim with a group of manta rays on the way back to town. It was uplifting to see the reef life thriving. Ningaloo has experienced isolated bleaching as recently as 2022, but has been spared the same type of mass bleaching events as have been seen on the east coast’s Great Barrier Reef. The flow of the prevailing current here in the west – the Leeuwin – and the more southerly latitude help provide a lower baseline sea temperature as a buffer against bleaching.

After our days on the water, we explored more of the interior of Cape Range NP, going deep into the wide open canyons of the range’s eastern side. In contrast to the narrow gorges of the western flank, the east is cut by huge valleys with towering cliffs up to 320m above sea level. The scenic vistas are endless, with views stretching across the range and out to Exmouth Gulf. We found a nice picnic spot for morning tea at the head of Shothole Canyon, with the valley’s red dirt reflected in the clouds above and the surrounding steep canyon walls. Not a bad spot for a cuppa!

At the end of our trip I was truly amazed when I reflected on how much we could see in just eight days – far more than I can fit in this article. The incredible variety of landscapes and wildlife in the region is genuinely spectacular. When you leave, it’s obvious you’ve been to a special part of our country, a wild place where nature remains free to carry on as it has done for millennia.

Izaac Blomley travelled courtesy of Australian Geographic Travel.