Ellie Duncan’s voice bounces around the cabin of our four-wheel-drive as we hit another bone-rattling track etched deeply with corrugations. “There’s plenty of tigers and bronzies. Then there’s the mantas, cowtails and eagles. And if you see a wedgefish, there’s a number you should call because they’re critically endangered and extremely rare,” she says, regaling us with a bucket list for underwater aficionados. “And whale sharks, we’ve seen 15 at a time cruising past here.”

We’ve pulled up on the windward side of Dirk Hartog Island/ Wirruwana on Western Australia’s sun-baked Coral Coast. “And plenty of humpies too,” Ellie continues. “And don’t even get me started on the mammoth bait balls we get. It’s so incredible to swim through them. They can last for weeks and attract, I reckon, thousands of feeding sharks.”

It’s 2pm on an early March day and the air temp is 30°C-plus. It’s a dry heat, and the breeze is picking up as we point the nose of the LandCruiser south-west towards Surf Point, where a lone dugong has been rummaging around in the seagrass beds for days – “growing fat and happy” in the turquoise waters around WA’s largest island. He’s disappeared now, though, and so we motor 10 minutes north to a bite of coast that broils with dorsal fins. Hundreds. “If we had more time, I’d get you in there,” Ellie says of the sicklefin lemon shark nursery. “They won’t bite – more afraid of you than you are of them.”

I long to wade in, too, not wanting to miss the opportunity to be the meat in this marvellous shark soup. But time is against us. We need to return to the homestead, pick up island director Kieran Wardle and skedaddle to the westernmost point of the island (and Australia) for what is widely billed as the country’s last sunset.

But more on that later…

Photographer Lewis Burnett and I arrive on Wirruwana via a charter flight from Denham – population 750, give or take a few. On the ground here, it’s all red dirt, stunted samphire, tin-can fishing shacks and an impressive array of new-money mansions built to withstand cyclone season.

In the air, a different tapestry unfurls. The very same red dirt acquiesces to an aquamarine sea, its currents shaping and reshaping the sandbars and inlets of Shark Bay, and a seagrass meadow that in 2022 was identified as the world’s largest plant. This ribbon of Posidonia australis covers more than 200km2 of the bay and began life about the time the ancient Egyptians were building the Great Pyramids, some 4500 years ago.

Flinders University ecologist Dr Martin Breed, who co-authored a study on the ribbon weed, says it’s like someone’s lawn: “It grows through rhizomes, underground suckers, and then it pops up and green shoots appear. What we’ve observed in Shark Bay is essentially an extremely large lawn that has expanded and grown across a very large area. There are some parts of the lawn that have died, but there are lots of parts that are still alive.”

After taking off in our little Cessna, we bank west towards Wirruwana and the enormity of the “lawn’s” reach is revealed. To the north and south, meadows stretch – a shorthand of dark dashes, dots and swirls; and among these are the outlines of something else: dugongs and dolphins and turtles and rays and a thousand fish species drawing sustenance from the rich pickings.

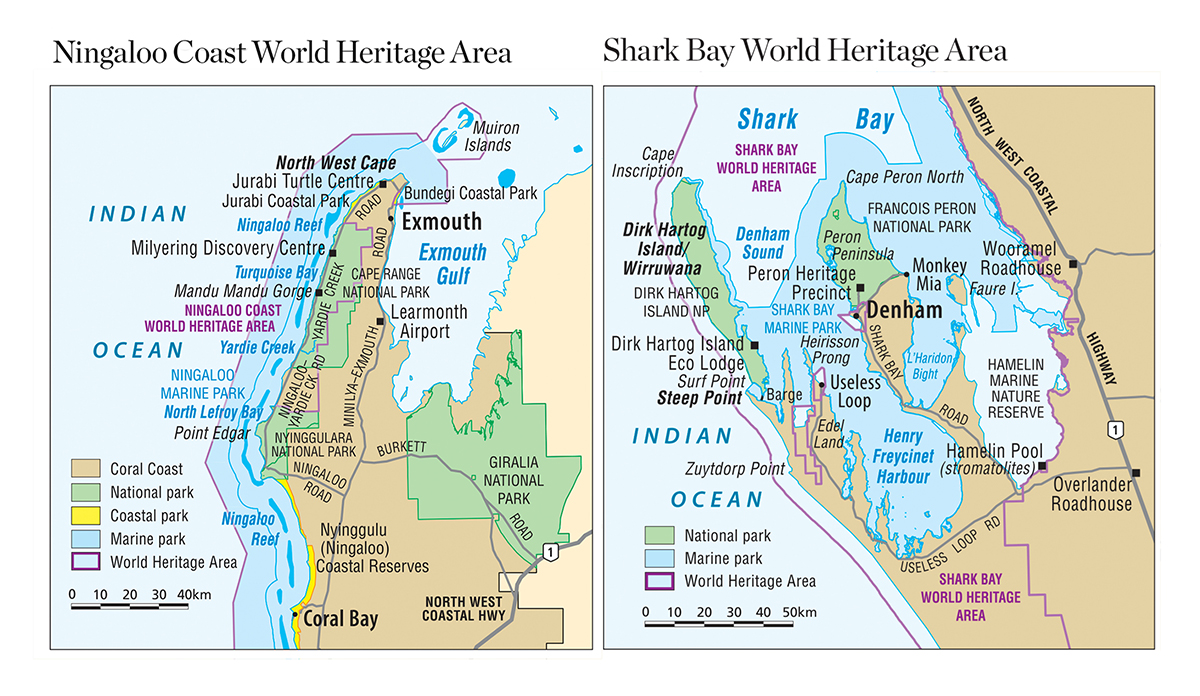

The Coral Coast of WA stretches – roughly speaking – 1200km from north of Perth to Exmouth, along idyllic and largely deserted beaches and through nature reserves bursting with plant life and bustling with native animals. The strip is punctuated by charming coastal towns nestled beside the shimmering Indian Ocean.

Our seven-day journey begins in WA’s capital, at Perth’s Kings Park and Botanic Garden, with Belinda McCawley, a forest-bathing specialist. “We’re going to hang out with this tree here for a while,” Belinda says, her words mingling with the calls of red-tailed and Carnaby’s black-cockatoos. “I’m going to invite you to be really curious about everything around you. This next practice is all about slowing down and taking in all the beauty around you.” We stand, silent, steeping our senses. I feel the wind, conductor of leaves; hear the birds, masters of song; and smell the nectar, sweet notes of natives.

Belinda grew up in Busselton, a 2.5-hour drive to the south, and spent her childhood playing in nature. “And when I was older,” she says, “it helped me through those tough teenage years. Although I didn’t realise it back then, it was this time in nature that made me aware of its therapeutic benefits and inspired me to study environmental science, so I could give back.”

It was 20 years into her career that she decided to turn over a new leaf and began the transition from corporate worker to woodland sprite. “Forest therapy was a lightbulb moment for me,” Belinda says. “I revelled in that deep connection and playfulness. I’ve been doing it for three years now.”

As a movement, forest bathing has been around for more than 40 years, when it was introduced in Japan as ‘shinrin-yoku’, which means taking in the forest atmosphere.

“First proposed in 1982 by the Forest Agency of Japan as a public health initiative, shinrin-yoku is now a recognised relaxation and stress-management activity and the practice is spreading around the world,” Belinda says. “It’s proven to decrease the stress hormone cortisol, and improve mood.”

And it’s not just anecdotal evidence that supports these claims. “Research shows trees emit phytoncides [wood essential oils], which are antimicrobial volatile organic compounds, such as alpha-pinene and limonene. Trees emit phytoncides to protect themselves from bacteria and disease. When we’re in the forest, we’re actually breathing them in, too, and they’ve been found to be beneficial to human health. They have all the antis – anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antifungal – and during the pandemic, research was conducted into phytoncides’ antiviral properties as well. So there’s scientific evidence to support why we feel so good when we’re with trees and in nature.” To reinforce her point, Belinda pulls a handful of leaves from her backpack. “These are the phytoncides,” she says. “Take a deep breath – it’s lemon-scented gum.”

I bury my nose. The smell is intoxicating, and I picture any ‘at risk’ cells within my body being thoroughly doused.

We walk on further, stopping to admire a trio of Carnaby’s munching on nuts in a grand marri tree. “I was here last night, on sunset, and the bird chatter was magnificent,” Belinda says. “When you slow down and just let yourself be, you open yourself up to all manner of magic.”

Pink as a pig’s ear and saltier than its bacon, Hutt Lagoon stops us in our tracks as we head north en route from Cervantes to Kalbarri on Day 2. The 70km2 lake is renowned for its hues of baby pink, salmon and blood-red – the result of Dunaliella salina, an alga that lives in the water and produces beta-carotene when exposed to sunlight.

Hutt Lagoon is separated from the Indian Ocean by a low-lying dune system. Locals such as Gavin Parker, with whom we spent last night stargazing, say you can swim here. But if you do, expect to exit the water somewhat pickled, and keep your thongs on – the bottom is lined with super-sharp salt crystals.

Gav runs tours to the Pinnacles in Nambung National Park, about 337km south of the lagoon, and we meet him about an hour before sunset amid the hundreds of limestone pillars that punch skyward from the coastal desert.

“The Pinnacles are made from golden quartz sand and limestone,” he says. “The latter came from seashells that were broken into lime-rich sands and blown inland. Over time, those sands calcified and turned into rock.

“Evidence suggests tuart forest [composed of the species Eucalyptus gomphocephala, which is a very tall eucalypt] grew out here, and the roots of the trees penetrated the rock, creating channels. Then a fire came through and destroyed all the vegetation. All that remained were the roots. Over time, water in the golden quartz sand seeped down through those channels and hardened, and that’s basically how the Pinnacles were formed.”

The outer portion of each is hard quartz sand while the inner core is softer limestone. “It’s thought they’re up to half a million years old but first appeared above ground 6000 years ago, based on the oldest Aboriginal artefacts that were found in the desert here. Since then, they’ve appeared and disappeared with the shifting sand. Most recently 450–500 years ago.”

According to Gav, the Dutch could see the Pinnacles Desert from the crow’s nests on their ships when sailing down the coast in the early 1600s. “They had it marked on some of their maps,” he says. “They thought it might have been a graveyard – looking like tombstones to them – but didn’t come ashore to have a look because the reef system goes out a long way and it was too dangerous. You can see we’re quite elevated here, above the ocean, so it would have been easy for them to spot.”

While the science of the Pinnacles is fascinating, it’s the Indigenous Creation stories that really captured the collective imagination of the tour group. The first was of the Yued, one of 14 clans of the Noongar, south-western WA’s First Nations people. “Local Elders say that these stories were told to try to discourage kids from coming out to the desert, because they might get lost,” Gav says. “They were told that if they did, the desert would swallow them up. The Pinnacles are the fingertips of the children who disobeyed their parents.”

Another is the story of Mulka and Djoondal, told to Gav by an Elder. “Mulka is the son of an Aboriginal woman and man who weren’t supposed to be together – they were from different skin groups. Because of this, he was born cursed, cross-eyed, and couldn’t throw spears straight. Instead, he used to hunt and eat the local children; they were much easier to catch.

“Djoondal is a spirit woman who lives in the sky. She has beautiful long white hair; it makes up the Milky Way. She saw Mulka eating the children so came down to Earth to save them. She gathered them in her hair and flew them into the sky. The stars you see are the children’s sparkling eyes.

“As the children grew, they scratched Djoondal’s head and their fingernails broke off and fell to Earth, landing in the desert and forming the Pinnacles.”

Landings on Wirruwana can be ‘interesting’. No falling fingernails, but the crosswinds, air-pressure pockets and dirt runway sure make it so. “It’s pretty spectacular flying here,” says our unflappable pilot Kyle, who relocated from flight training school in Tassie to Denham 12 months ago, and gets us down safely on Day 4. “Although on 45°C days [routine in summer] it’s not so much fun.” Agreed. Lewis and I had all windows wide open on the flight and were still dripping; the mercury hadn’t even tipped 40°C. Thankfully, flying over seabeds and channels with evocative names – Angel’s Wings and Tree of Life – was remarkably distracting.

Tory Wardle meets us at the end of the strip. She and husband Kieran have lived on Wirruwana since the early 1990s, raising their three children here, sans shoes, shirts and most of the other trappings of mainland life, while running Dirk Hartog Island Eco Lodge. But the island has been in the family far longer. Kieran’s grandfather, Sir Thomas Wardle, bought it in 1969, retreating from his duties as lord mayor of Perth in favour of fishing the island’s abundant waters. Kieran was seconded to manage Wirruwana at the tender age of 19, and apart from weekly footy trips to Perth to catch up with mates and the odd family holiday, he’s never left. As for Tory, well it’s a classic girl meets boy story. Girl comes to work as a chef on boy’s island. Girl also never leaves.

Up until 2009, the island was also home to 8000 or so sheep, and about the same number of goats. Feral cats were also abundant. In partnership with WA’s Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA), the Wardles helped remove all of these (either pontooning them off the island, shooting or baiting them) to make way for a native species reintroduction program as part of the Dirk Hartog Island National Park Return to 1616 Ecological Restoration Project.

When Dutch explorer Dirk Hartog visited the island that now bears his name on 25 October 1616, it was a native animal ark. During the ensuing years, after colonisation (by both European humans and feral animals), 10 species of small placental mammals and marsupials, and the western grasswren, were wiped out. All are in the process of being returned to Wirruwana, with rufous and banded hare-wallabies, the boodie, dibbler, woylie, greater stick-nest rat and Shark Bay bandicoot now thriving.

We see evidence of this firsthand while returning from sundowners at the island’s westernmost point – tiny Shark Bay mice dart across the sandy track, and rufous hare-wallabies (mala) sit stock still, mesmerised by the golden beam of our headlights.

“Along with the native animals, the island’s plants have rebounded brilliantly too,” Kieran says. “Like the Dampier’s rose, which was actually the first botanical specimen ever collected in Australian colonial history, in 1699 by William Dampier, and the native hibiscus.

“The chuditch [western quoll] is the last on the list for reintroduction. It’ll be amazing to see its spots and dots disappearing into the undergrowth in the years to come.”

Eruption!” The cry comes from 5m to my left, followed by a mini stampede. Across the dunes people rush, children and adults alike, eager to witness the event. I hang back. A turtle eruption is a sacred thing – life beginning and oftentimes ending all in a matter of minutes – and I’m concerned all those feet will create chaos for the hatchlings. It’s Day 6 and Lewis and I have come to Jurabi and Bundegi Coastal Park, on the Ningaloo (Nyinggulu) Coast, a short drive from Exmouth, just before sunset in the hope of photographing an eruption. Green, loggerhead and hawksbill turtles breed in the shallow waters here between September and December, with females coming ashore to nest. Roughly 60 days later, hatchlings begin to emerge.

Although the DBCA has published a code of conduct for turtle nesting and hatching, which you can find on its website, it’s obvious that all but a handful of the 60 or so people on the beach this afternoon have either not read it or simply don’t care about following the protocol.

It clearly states that very few turtle hatchlings survive to reach adulthood after the nest erupts, contending with hungry gulls on their perilous dash to the sea and once the hatchlings reach the water.

The code asks people to:

• Let them flow – allow hatchlings to make their own way to the ocean. They take a magnetic imprint of the beach, which allows them to return to their birthplace in adulthood. Don’t get between hatchlings and the ocean, stay still and allow a clear path to the water.

• Stay below the dunes – avoid trampling on nests and emerging hatchlings. Walk along the water’s edge to minimise disturbance.

Instead, people surround the nest as it erupts, blocking both the light of the setting sun and the path to the ocean.

The Ningaloo Coast’s tourism boom during the COVID years has been monumental – WA residents roamed while the rest of the country was locked out, many spending big on luxury 4WDs and boats, towing them north to explore the riches of the region. Social media accounts, too, and the rise of #vanlife, celebrated the region’s exquisite natural beauty – its red earth, turquoise water and dramatic coastal ranges – as well as its extraordinary wildlife, including the world’s largest fish, the whale shark.

Most of the whale sharks that ply the waters of Ningaloo Reef are juvenile males. You can swim with them via an organised charter from March–August.

We’d spent our morning aboard the 60-foot catamaran, Windcheetah, dipping in and out of the waters of Ningaloo Marine Park, home to one of the world’s largest fringing reefs and one of the most reliable places to swim with these behemoths. The cohort here, mostly juvenile males measuring about 5m, will grow up to 20m in length.

Before swimming, however, our ability was assessed in the park’s relatively shallow inner reef. Underwater, a world of coral bommies and kaleidoscopic fishes revealed itself, and Ash Jansen, our on-board photographer, schooled us in how to best position ourselves for a photo when a shark passes by.

Back on the catamaran, we were divided into two groups – no more than 10 people can swim with a shark at any one time – and the rules of engagement were explained.

“You’re going to be dropped into open ocean and need a level of comfort around that,” Ash said. “And you’re most likely not going to be able to see the bottom. If you’re not okay at any time, your in-water guide will be there with a float for you to hold onto. You can’t try to touch or ride on a whale shark. You can’t get closer than 3m from the head or body, and 4m from the tail. And you can’t use flash photography.”

Working in tandem with our vessel was a spotter plane, and before long it had a swimmer in its sights. The skipper pushed the throttle forward and positioned Windcheetah in the path of the oncoming shark (the minimum approach distance is 30m). And then we jumped in, bobbing like corks as our guide lined us up for optimum viewing. “Heads down, heads down,” Ash yelled. And as we did, it swam by, giant filter-feeding mouth agape and massive caudal fin swinging hypnotically from side to side. Extraordinary indeed.

Our next encounter came just 20 minutes later, with a ‘bubble chaser’, a colloquial term for a whale shark that likes bubbles. “They mistake them for food, so if you get caught in front of one, move to its side as quickly as you can without creating bubbles [from kicking or splashing], otherwise it’ll chase you,” Ash advised. One of our swimmers did, and it did, and the pair had to be separated.

By our fourth shark, we were well versed in the practice, and I swam alongside it, eye-to-eye for a time, marvelling at its inky cloak and glowing white spots until it slid silently into the big blue and finally disappeared from view. Back on the boat it was a slow and splendid return to shore, with one final stop for a snorkel with a wizened sea turtle.

Much like all our days on the Coral Coast, this last one was golden. From forest bathing to pink-lake gazing and shark chasing, we both had a whale of a time.

Top 10 things to do on WA’s Coral Coast:

1. Forest bathe in Kings Park and Botanic Garden – Mindful in Nature

2. Explore the other-worldly landscape of the Pinnacles, Nambung NP – Lumineer Adventure Tours

3. Count the stars and satellites at Kalbarri – D’Guy Charters

4. Haul out on Dirk Hartog Island to swim with sicklefin lemon sharks and toast Australia’s last sunset – Dirk Hartog Island Eco Lodge

5. Hike the extraordinary limestone Cape Range NP – Trek Ningaloo

6. Swim with whale sharks in World Heritage-listed Ningaloo Marine Park – Ningaloo Discovery Tours

7. Witness a turtle eruption in Jurabi and Bundegi Coastal Park, Exmouth – exploreparks.dbca.wa.gov.au/park/ jurabi-and-bundegi-coastal-park

8. Frolic with sea lions at Jurien Bay – australiascoralcoast.com

9. Marvel at the pastel hues of Hutt Lagoon – australiascoralcoast.com

10. Discover the stromatolites and thrombolites at Lake Thetis – visitpinnaclescountry.com.au

Australian Geographic thanks Tourism WA for its assistance with this story.