Ever seen a koala in the tropics? Probably not

Meet Athey, an exceptionally rare far north Queensland koala.

He was rescued from a suburban power pole in the town of Atherton, south-west of Cairns, in the Tablelands Region.

Locals around here are far more likely to spot a tree-kangaroo than a tree-climber of Athey’s kind.

That’s because this far north koalas are at the very edge of their normal distribution and almost never seen.

“They’re scattered through wet eucalypt forest fringing the southern Atherton Tablelands, and along rivers in drier country to the west,” wildlife biologist Roger Martin explains.

“But they’re sparse. There have only been 20 or so reported in the last few decades.”

Distracted by tree-kangaroos

Roger had been fascinated by these far-flung koalas for years but was preoccupied with the region’s tree-kangaroos. Athey changed all that.

“Athey forced us to commit,” Roger says.

Now he and wildlife vet Dr Amy Shima spearhead the Tree-Kangaroo and Mammal Group’s koala project, which surveys Atherton Tablelands koalas as part of the National Koala Monitoring Program – a joint project between the federal government and CSIRO.

When Athey was rescued in late 2021 he had an eye infection and needed care.

But no one knew what to feed him. Koalas are notoriously fussy eaters with narrow dietary preferences, eating the leaves of only a small number of eucalypt species.

“He just turned up. We weren’t prepared,” Roger says. “We wondered what koala food trees are here. What would he eat?”

Amy and Roger solved Athey’s dietary dilemma by offering him a cafeteria of different leaves to browse provided by North Queensland tourism group CaPTA.

The family-owned company owns a eucalypt plantation where food is grown for koalas in its local wildlife parks.

Athey went for Queensland blue gum. “He loved it,” Roger says. “He also got stuck into gum-topped box and lemon-scented gum, especially new growth.”

Once Athey’s eye infection cleared, he was relocated to a safe site away from cars and dogs, rich in the food trees he ate while in care.

A personal meeting

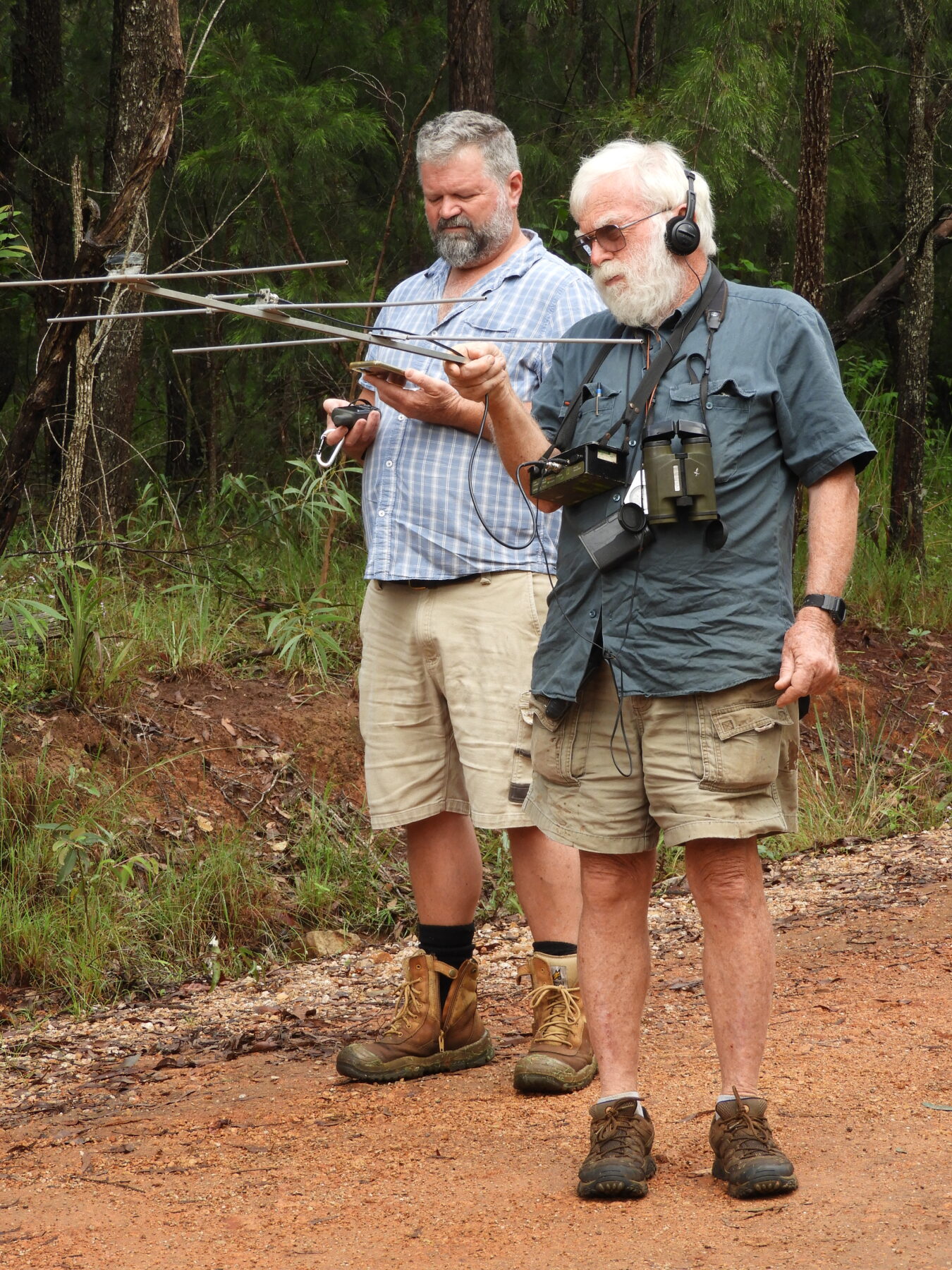

I recently accompanied Roger and Amy to meet with the special marsupial.

We were a mere 300m from where he was released but it took a while to spot him, despite a strong ping from the radio collar he’s been fitted with telling us he was nearby.

When we finally spotted Athey, he was 20m up a gum-topped box.

His short, pale grey fur, which is typical of a far northern koala, blended into the smooth bark of the tree’s branches. Koalas tend to become larger overall and their fur thicker and darker the further south they live.

“His eyes look clear, and his backside looks clean,” Amy said, peering through binoculars as she looked Athey over for any signs of disease.

The forest reminds Roger of southern states where he’s studied koalas. “It’s a bit like a southern forest because of its elevation,” he told me. But this forest has a summer wet season.

“It will always be wet as long as there’s a Coral Sea [off Australia’s north-east coast] and a prevailing south-easterly,” Roger explained.

Fires aren’t frequent in Far North Queensland’s wet eucalypt forests. And when there is a burn, it’s cooler than in bushfires in the south.

Important survival genes

The tiny koala population surviving in Far North Queensland’s wet refugia could turn out to be critically important for the long-term survival of the species elsewhere.

“As it gets hotter and drier, [this is] where koalas will be when they’re gone from elsewhere,” Roger explains.

Little is known about koalas in the far north and their status as the endangered species’ northern outpost makes it crucial to learn more.

“We really want to know how the females are doing, because their fertility is key,” Amy says. “If they have reproductive tract Chlamydia, their fertility may be low.”

Koalas are prone to the sexually transmitted bacterial infection know as chlamydia, which affects their fertility and overall health.

Amy and Roger haven’t located any female koalas yet, but they hope Athey will lead them to some.

In search of females

Last July, during the breeding season, Athey went west.

After 10 days, when the koala team caught up with him, he’d walked 12km and his nose sported a puncture wound. “We think he met a female,” Roger explains.

A new solar-powered satellite transmitter fitted to Athey’s collar will help the koala team keep tabs on Athey during the next breeding season.

“With 5m-accuracy, the satellite tag should help us be more efficient,” Amy says. “We’ll be able to see if Athey has moved, where he’s moved to, and head out to find him when it looks like he’s doing something interesting.”

Acoustic recorders, to detect and log koala calls, are another addition to the team’s technology tool kit.

Koalas make a lot of noise in the breeding season.

Amy, Roger and their team hope that by placing recorders where Athey is bellowing they’ll be able to pinpoint females from the raucous encounters of mating pairs.

Geographer Richard Hopkinson, the team’s drone operator and spatial information specialist, is a self-confessed koala convert.

“I like tree-kangaroos, but the koalas present a greater technical challenge,” says Richard, who’s added koala-call analysis to his task sheet.

For now, the team’s challenge is to catch Athey and fit his satellite tag.

But he’s been out of reach, and the day I met Athey was no different.

“He’s just eating and sleeping,” Amy sighed. “It’s still worth seeing him though,” Roger said. “To see his disdainful look as he moves further up his tree!” “Not today, little man,” he said. “You win this round.”