Wombat dental gags and monster whale needles: meet the designer developing life-saving tools for our wildlife

A wombat’s teeth don’t stop growing. Those fibrous native grasses of the Australian landscape that the bulbous marsupials can be seen grazing upon neatly file their teeth down to a healthy size. However wombats kept in captivity can have a much harder time keeping their molars in check. Unable to perfectly replicate wild diets, veterinarians often have to grind a wombat’s teeth down manually otherwise the teeth grow so big they begin to pierce the animal’s cheeks.

These dental appointments aren’t as straightforward as they sound. Throughout the procedure, a nurse has to hold open the wombat’s mouth, dilate the animal’s cheeks and also check vitals. That its mouth opens between just 30–40 degrees means limited access is available. This is the sort of veterinary surgical conundrum that engineer and industrial designer Girius Antanaitis plays over in his head.

“It was an extremely difficult and frustrating procedure to assist these wombats,” Girius says. “It never got done perfectly because there was never full access to the wombat’s mouth. For me, it was a matter of spending time with veterinarians analysing the issue and seeing how difficult it was to treat wombats with the instruments they had.” The wombat dental gag holds the wombat’s head in a sturdy position while keeping the mouth wide open for the entire duration of the procedure. First developed at Healesville Sanctuary in Victoria, Girius has since donated the dental gag to several other wildlife hospitals around Australia.

In Girius’s view, a lot of the surgical instruments currently used by wildlife veterinarians aren’t fit for purpose. However, making alternatives for uncommon procedures such as a wombat dental check-up is time consuming and expensive. A single tool can involve days in operating theatres shadowing veterinary surgeons, analysing videos of an animal’s motor skills, pouring over x-rays and making surgical sketches and prototypes. “No one’s really helping wildlife veterinarians develop necessary apparatus because it doesn’t generate any money like tools for domestic or livestock animals would,” Girius says. Castration forceps or equine dental kits don’t excite this Lithuanian-Australian, whose first name translates to forest. “My parents gave me that name because of what it means and what it stands for.” Instead, he seeks out complex problems requiring unconventional answers.

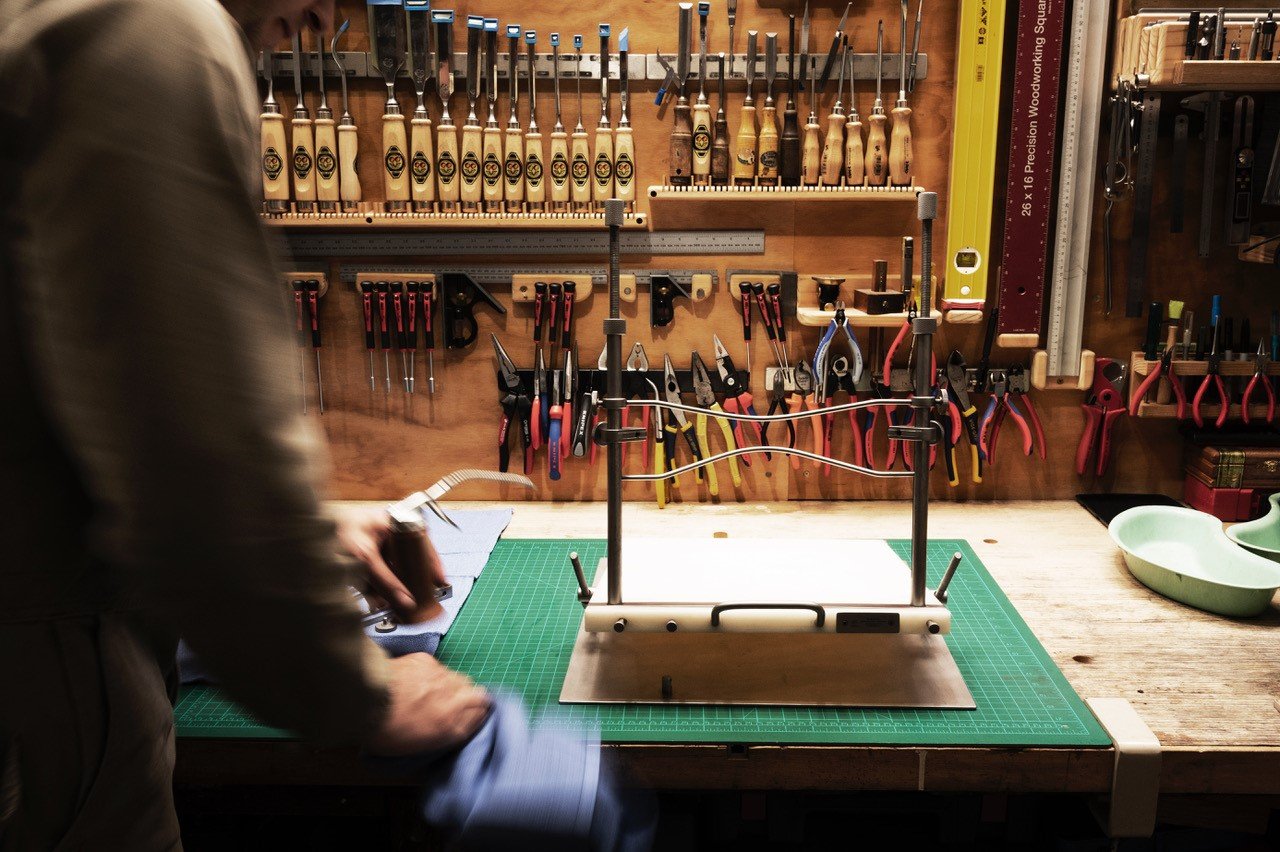

Located in the Melbourne suburb of Balwyn North, Girius’s workshop looks exactly as you’d expect an engineers workshop to, except for a few peculiar items. Take for instance a metre-long whale needle. Stranded whales are typically euthanised using firearms and explosives – it’s gruesome and impractical, which is why there’s a strong push within Australia to change this. Recently, Girius has been commissioned by an advisory board to the Australian Federal Government to develop a standardised kit to euthanise stranded whales humanely. “To euthanise a whale you need a monster needle,” he says. “First you inject the muscle relaxant. After that kicks in, the intracardiac needle goes into the heart and the whale can be euthanised painlessly.”

Then there’s the cracked shell of an eastern long-neck turtle, recently lent to Girius by a wildlife hospital who have asked him to find a new way to repair the fractures. “At the moment, vets mostly use fibreglass or epoxy resins on cracked turtle shells. It’s not the best method because, like human skin and nails, chemicals applied to the turtle’s shell can be absorbed into their body. It might be a common practice, but it isn’t ideal. My idea is mounting a plate externally with screws that go to a specific depth so as not to harm the turtle.”

What you’ll mostly find Girius working on, however, are his avian orthopaedic surgery kits, which are basically tiny versions of normal surgical tools. With bones thinner than toothpicks, avian orthopaedic surgery is a delicate process. “When operating on small birds, it’s all about control. It’s difficult to have good precision when the surgical tools are too large. Often I see the potential for these things before the vet just because they’re very used to working with what they have and there are a limited number of people willing to make the tools for them, but I have a mind that’s wired to design and passion for birds.”

Often I see the potential for these things before the vet just because they’re very used to working with what they have and there are a limited number of people willing to make the tools for them.

Since first emailing Healesville Sanctuary back in 2014 offering a helping hand, Girius has become the go-to person for complicated veterinary surgical solutions. Two years ago, he was contacted by veterinary specialist surgeon Dr Gordon Corfield who was desperate to begin work on Hitam, a sun bear rescued from a home in Indonesia. Hitam had been kept in a cage and fed a diet of rice and milk, which had stunted her growth. Her pelvis had not grown to the size it was meant to and it was painful for her to go to the toilet. Vets had two choices: operate or euthanise. The surgery would be considered a world-first and the implant would have to be built from scratch.

“Gordon called me because none of the big orthopaedic companies were interested in helping them. I’ve never done an implant for a mammal before and so I thought, ‘this is definitely something that I’d like to help them with’.” The implant Girius constructed successfully widened Hitam’s pelvis so that she could pass faeces without pain. Hitam is now living out her life at a sanctuary in Borneo. Girius’s work on Hitam, like many of his projects, was self-funded. Customised orthopaedic implants like Hitam’s are expensive and unlikely to be used again, given her extraordinary circumstances. This is Girius’s bread and butter. “I’m not really interested in tools with vast applications. What’s important to me is the animals no-one’s helping. I ask myself, ‘what’s the next small thing, not the next big thing’.”