Inside Australia’s first mobile veterinary hospital

THE LETTER IN the gold frame on the wall is in mint condition, but its words are hard to decipher. “That’s what a 94-year-old’s handwriting looks like,” says Dr Stephen Van Mil, founder and CEO of the Byron Bay Wildlife Hospital (BBWH).

The letter is from Stephen’s “absolute hero”, Sir David Attenborough, to whom he wrote asking for his endorsement of a wildlife project documenting platypus activity in Victoria. The monotreme is said to be one of Sir David’s favourite animals, and although he declined the request for his support on that project, Stephen was nevertheless “thrilled” to receive the personal response.

This year the legendary naturalist and documentary filmmaker turned 95 and the milestone has Stephen wondering who might take his place. “There’s no-one to replace him,” he laments. The legacy of such a global icon will indeed be huge, but Stephen is motivated to play his own small part in honouring it through the establishment of Australia’s largest mobile wildlife veterinary treatment centre – the BBWH. “He’s a man with a mission,” Dr Bree Talbot, the facility’s foundation vet, says of Stephen.

That mission began early in life: Stephen recalls the day when, as a five-year-old, he told his parents he would one day become a vet. “I loved animals,” he says, “and I never entertained anything else, to be honest.” He was particularly interested in wild animals, caring for injured and orphaned creatures he found on bushwalks as a child. Stephen followed his passion and graduated as a veterinary surgeon in 1984.

Since 2014, he’s lived in the Byron Bay area of northern New South Wales, a region rich in native creatures but also close to areas of busy human activity serviced by fast roads.

Stephen witnessed the dilemma of injured wildlife being brought into busy vet clinics where they would have to wait for moments of downtime to be treated. It would regularly take hours for vets to be available to treat the animals, which they often did in their own time and at their own expense. “Wildlife often plays second fiddle,” Stephen comments.

Two and a half years ago Stephen decided to do something about what he saw as the crisis facing wildlife in his area. Together with his friend and veterinarian colleague Dr Evan Kosack, he began developing the idea of a dedicated wild animal hospital.

Initially, the BBWH was intended to be a regular bricks-and-mortar clinic. But government red tape led the two vets to consider the alternative option of a mobile hospital.

It was a novel idea and there was nothing else like it in Australia, “so we literally started from scratch”, Stephen says.

With a solid idea, but lacking any kind of government support, a public funding campaign was launched in June last year, during the early months of the COVID pandemic. It was quickly successful, and, with initial designs gaining formal approval by October, Stephen and Evan took delivery on 26 November of a 16m-long semitrailer.

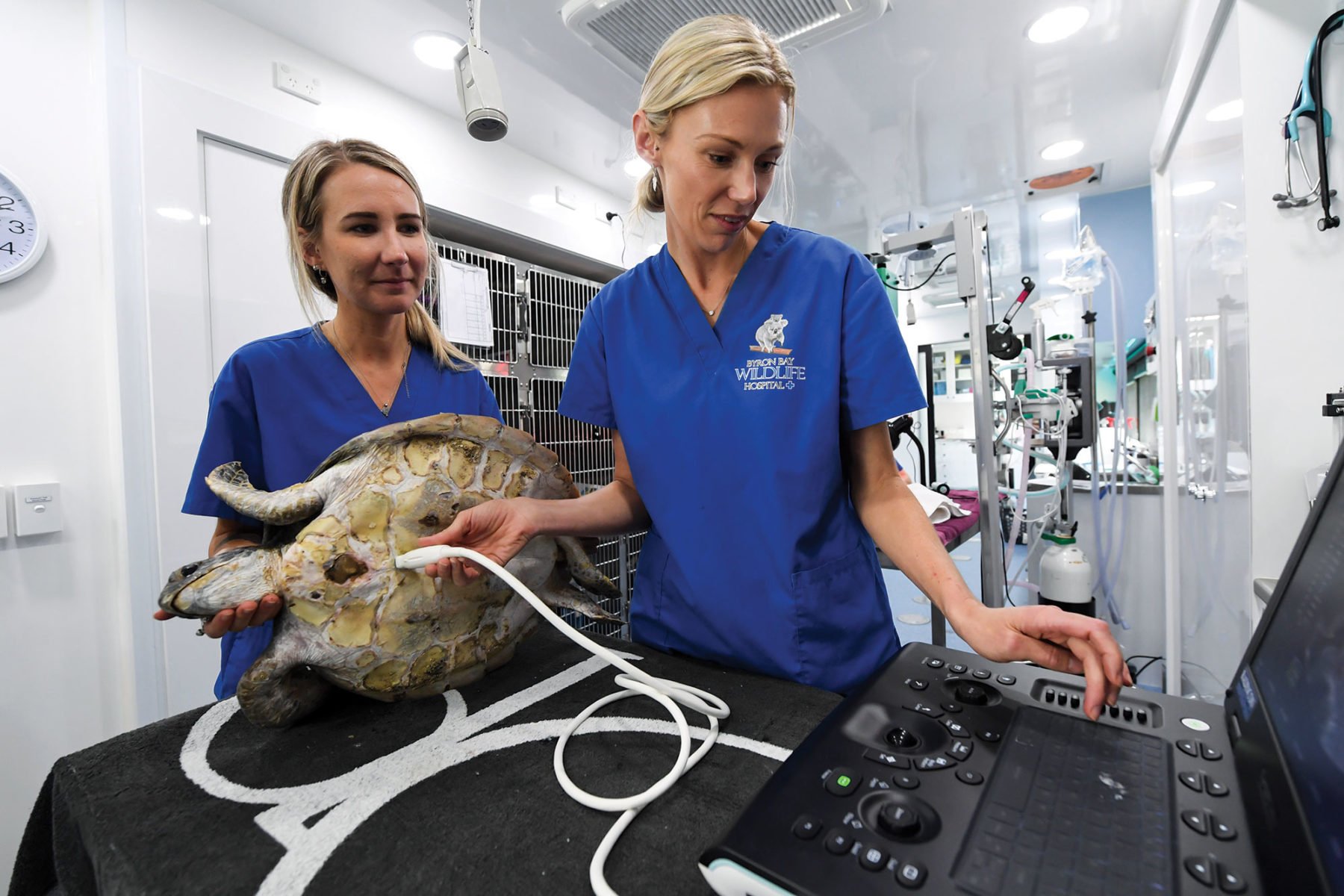

Work began on its transformation into a fully functioning emergency animal hospital complete with operating theatre. A vet team led by Bree began working full-time in February out of the mobile hospital, which is stationed on donated land just outside of Byron Bay. It’s hoped that the state-of-the-art facility will provide the chance for immediate responses to injured and traumatised native animals in future crises such as bushfires and floods, anywhere in Australia.

One of the hospital’s first patients was April, a green turtle picked up in September last year by Australian Seabird Rescue. She was found in severe distress after ingesting discarded rope. Bree removed the rope in a complicated surgical procedure, and after almost three months of rehabilitation, April was released back into the ocean – the clinic’s first major success.

So far, the clinic has remained stationary, except for a publicity tour in May this year. That event saw the semitrailer hitched to its own brand-new customised UD (Quon) prime mover, donated by Volvo Group Australia, and taken on the road. Travelling between Brisbane and Coffs Harbour, it showcased its groundbreaking capabilities.

Even as a stationary unit the facility has been in demand, with Bree and her team busy treating a stream of injured creatures brought in daily to where it’s based at Ewingsdale.

Stephen has enjoyed a distinguished and varied career as a vet, filmmaker and media identity, and now with the mobile hospital up and running, all his interests have come into alignment. “I guess,” Stephen says, “I’ve been very fortunate with creating a project that encompasses my veterinary background, my passion for conservation, and my media skills and connections.”

Stephen’s days can fill with countless meetings in an instant, but he tries to work in the hospital at least two days a week. Although he doesn’t have the skills of a dedicated wildlife vet such as Bree, he’s eager to learn from her and her expert team.

“No two days are the same, and every day is unpredictable,” says Stephen, who’s constantly coming up with new ways to improve the service.

“Sometimes I will get messages at four in the morning, and he’s already up thinking about something and gets excited to tell me,” Bree says.

Stephen has plans to roll out a series of similar mobile hospitals nationally and internationally. A new mobile hospital planned for Victoria has detachable units, so sections can be transported by air to islands or remote locations. The existing mobile hospital is attracting interest from New Zealand, the USA and Tanzania.

Stephen’s busy schedule also includes a 10-part TV series, Wildlife Rescue Australia, for which filming has already begun. It will showcase the work of the BBWH when it airs this summer on Channel 10. “We’re sort of being pulled in all directions, in a good way,” Stephen says, laughing.

He’s also advocating for the teaching of wildlife medicine and surgery in Australia’s university veterinary courses, because the average suburban vet will usually be the first contact for members of the public trying to help an injured wild animal.

“It doesn’t matter how many wildlife hospitals we build, injured wildlife is still going to go to general vets every day,” Stephen says.