Indeed, Australia has a seriously good selection of weird moths

By now you’ve probably heard of the giant wood moth that made its way down from a rainforest and into a south-eastern Queensland school. Known as one of the biggest moths in the world, with a wingspan of up to 25cm, it shocked the tradie that found it and amazed the school students, who have since started a creative writing project based on the moth, which involves their teachers being eaten by them. Kids, you’ve gotta love ’em.

Giant wood moths can commonly be found along the Queensland coast and around suburban Brisbane where they hide out on the trunks of smooth-barked eucalyptus trees, rarely giving the public the opportunity to see them. While their rarity and size gives them a bit of attention, they’re not the only cool moths that call Australia home.

We know of around 22,000 species in Australia, and among those are some seriously charismatic and colourful characters. So much so that they’ll turn the idea of moths as the ‘ugly sister’ of butterflies on its heads. Here are a few of our favourites.

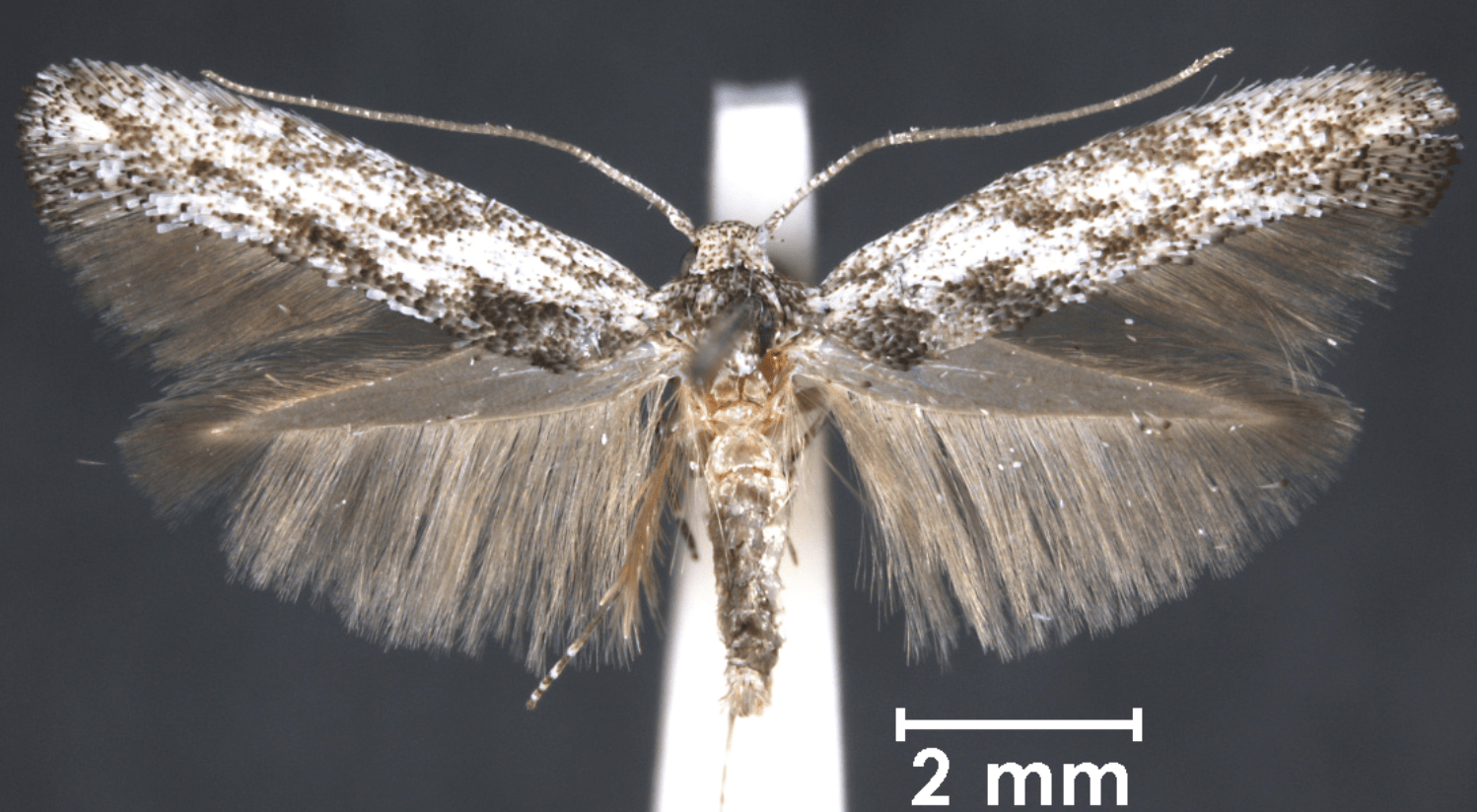

Scribbly gum moth

If you’ve ever come across a smooth-barked eucalyptus tree decorated in hundreds of swirling, scribbly lines, you may have wondered what or who exactly is responsible for this.

Initially believed to be the work of beetle larvae, it wasn’t until the 1930s that CSIRO entomologist Tom Greaves discovered that it was instead the markings of a small undescribed moth, Ogmograptis scribula.

The scribbly gum moth mines its way through the growth layer of the bark, from which cork is made, leaving behind the familiar loops, twists and lines on the surface of the eucalypt. So, next time, you see a scribble on a eucalyptus tree make sure you stand back and appreciate the handiwork of Australia’s first bush artists.

Creatonotos gangis

If you’ve never heard of ‘hair pencils’ before, feast your eyes on the bizarre Creatonotos gangis. This moth takes courtship so seriously it spreads its pheromones using enormous, inflatable appendages that unfurl from deep inside its abdomen.

Found in the northern regions of Western Australia, the Northern Territory and Queensland, and all across South-East Asia, this moth has evolved an ingenious way to find mates – even if they’re several kilometres away.

Hair pencils are highly specialised structures that can be found in many male butterflies and moths from the Lepidoptera insect group.

Also known as coremata (which means ‘feather dusters’ in Greek), they’re used by the males to waft a heady cocktail of chemicals into the surrounding environment.

Enigma moth

You know when you buy cheap Christmas decorations of little reindeer, robins or rabbits, and they’re super-sparkly and just a little bit ill-proportioned because they were mass-produced with several million other reindeer, robins and rabbits? That’s kinda what this little moth looks like. Slightly off, but so Christmassy.

Meet Aenigmatinea glatzella, commonly known as the enigma moth. Recently discovered (and reported in January 2015) among the native pine trees of Kangaroo Island, which sits 112km south-west of Adelaide, the moth is so entirely unique scientists are calling it one of the most exciting entomological finds in the past four decades.

Why so special? Well for one, it’s the only member of the Aenigmatineidae family, because there’s no other known species of moth that exhibits the same features. And on top of that, its defining features – its mouth parts and genitals – are oddly primitive, meaning they don’t show evidence of millions of years of evolution like the vast majority of moth and butterfly species we know about.

Bogong moth

After emerging in spring on the plains of southern Queensland, NSW and Victoria, some two thousand million bogong moths (Agrotis infusa) migrate up to a 1000km to spend summer in granite caves and crannies in the Australian Alps. Not for food or mates do they travel, but just to rest. After spending summer aestivating (hibernating) they return to the plains to breed. It’s this mammoth migration that makes them so well-known in Australia.

It’s a puzzle that’s mystified scientists for decades. Just how does the bogong moth navigate each spring from the hot and arid plains of southern Queensland, north-western NSW, western Victoria and SA to the cool environment of the Snowy Mountains, and then complete the return journey 3–4 months later?

During some years the much-maligned moths are blown off course or attracted by city lights, as famously occurred in September 2000 when the opening ceremony of the Sydney Olympic Games was besieged by the flying insects.

When, three years later, they descended in their millions on Parliament House in Canberra during a visit by US president George W. Bush, some politicians, annoyed by bogongs swimming in their coffee, called for the use of insecticide to discourage the multitude of interlopers.

Moths that successfully make it all the way to the Australian Alps, a remarkable journey that’s longer in some cases than 1000km, shelter and feed at lower altitudes until the snow melts and they can access summer hide-outs on the roof of Australia.

Pellucid hawk moth

Meet the pellucid hawk moth (Cephonodes hylas), a gorgeous cross between a moth, a cicada and a glasswing butterfly.

At home in an array of habitats across Africa, India, Southeast Asia and Queensland, Australia, this strange little species starts off as a bright green caterpillar, feeding upon some of the finer things in life – coffee and pomegranate plants – wherever it can find them.

Just a handful of species in order Lepidoptera, which includes all butterflies and moths, have scaleless, transparent wings. So, you might be wondering what the point of them is, when coloured wings can serve so many functions, including communication, defence, thermoregulation, feeding and waterproofing.

Having observed them at a nanoscale, researchers suspect the point is to achieve ‘antireflection‘ – minimising the shine produced by a surface when the light hits it, so basically the glass wings act as an invisibility cloak.