Scientists raise alarm on 26 species of butterfly at risk of extinction

It might sound like an 18th century fashion statement, but the “pale imperial hairstreak” is, actually, an extravagant butterfly. This pale blue (male) or white (female) butterfly was once widespread, found in old growth brigalow woodlands that covered 14 million hectares across Queensland and News South Wales.

But since the 1950s, over 90% of brigalow woodlands have been cleared, and much of the remainder is in small degraded and weed infested patches. And with it, the butterfly numbers have dropped dramatically.

In fact, our new study has found it has a 42% chance of extinction within 20 years.

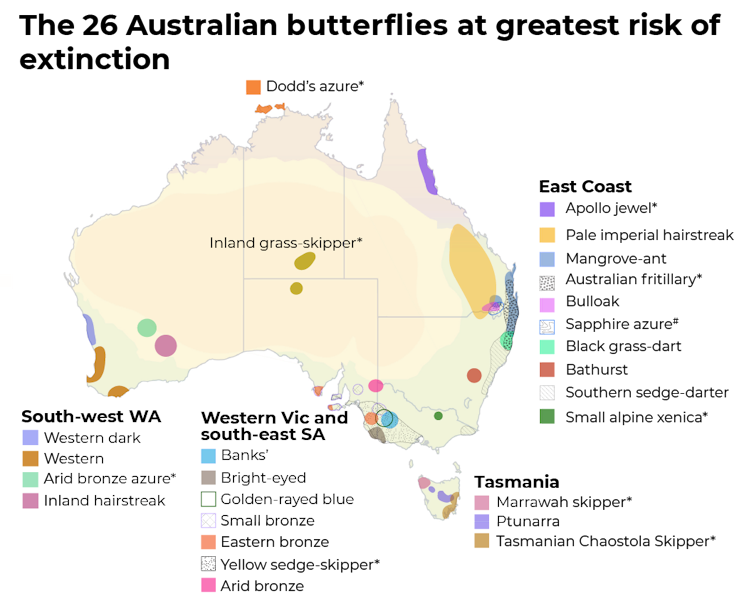

It isn’t alone. Our team of 28 scientists identified the top 26 Australian butterfly species and subspecies at greatest risk of extinction. We also estimated the probability that they will be lost within 20-years.

Without concerted new conservation effort, we’ll not only lose unique elements of Australia’s nature, but also the important ecosystem services these butterflies provide, such as pollination.

Only six are protected under law

We are now sounding the alarm as most species identified as at risk have little or no management underway to conserve them, and only six of the 26 butterflies identified are currently listed for protection under Australian law.

The good news is there’s still a very good chance of recovery for most of these species, but only with new targeted conservation effort, such as protecting habitat from clearing and weeds, better fire management and establishing more of the right caterpillar food plants.

Let’s meet a few at-risk butterflies

The butterflies identified are delightful and fascinating creatures, with intriguing lifecycles, including fussy food preferences, subterranean accommodation and intimate relationships with “servant” ants.

The Australian fritillary

Our most imperilled butterfly is the Australian fritillary, with a 94% chance of extinction within 20 years. Like many of our butterfly species, a major threat facing the fritillary is habitat loss and habitat change.

The swamps where the fritillary occur have been drained for farming and urbanisation. At remaining swamps, weeds smother the native violets the larvae depend on for food.

No one has managed to collect or take a photo of a fritillary in two decades, although a butterfly expert observed a single individual flying near Port Macquarie in 2015.

It might already be extinct, but as it was once quite widespread at swampy areas along 700 kilometres of coastal Queensland and NSW, we have hope there are still some out there.

The fritillary has impressive jet black caterpillars with a vibrant orange racing stripe and large spikes along their back, which transform into stunning orange and black butterflies.

Anyone who thinks they have seen a fritillary should record the location, try to photograph it and the site and immediately contact the NSW Department of Planning Industry and Environment.

The fritillary is among many butterflies with specific diets. And these preferences can make species vulnerable to environmental changes such as vegetation clearing, weed invasions and fires.

The small bronze azure

Caterpillars of the small bronze azure — found on Kangaroo Island (and a few other patches in South Australia and Victoria) — only eat common sourbush.

Following the extensive 2020 fires, the butterfly hasn’t been found in areas where the sourbush burnt. Luckily, it’s been found in small patches of unburnt vegetation, so for now it’s hanging in there.

Like many butterflies, the lifecycle of the small bronze azure is enmeshed with a specific species of ant.

By day the butterfly larvae shelter underground in sugar ant (Camponotus terebrans) nests, then at night they’re escorted up by the ants to feed on the sourbush. For their care the ants are rewarded by a sugary secretion the caterpillars produce.

The eastern bronze azure

Some relationships with ants are even more unusual. Kangaroo Island’s other imperilled species — the eastern bronze azure — stays underground in sugar ant nests for 11 straight months. We don’t yet know what they eat.

In a macabre twist, they may be eating their hosts — the ants or the ant larvae. So why the ants carry them down and look after them is also a mystery.

It might be for sugary secretions, like with the small bronze azure, but the caterpillars could also be using chemical trickery, mimicking the scent of ant larvae to fool the ants.

Adults of the eastern bronze azure emerge only to flutter about for a few weeks in November, so at the time of the Kangaroo Island fires in January the entire population was safely underground in ant nests. And as the larvae don’t come up to feed on plants, they weren’t impacted by the loss of vegetation.

It’s not too late to save them

By raising awareness of these butterflies and the risks they face, we aim to give governments, conservation groups and the community time to act to prevent their extinctions.

Local landowners and Landcare groups have already been playing a valuable role in recovery actions for several species, such as planting the right food plants for the Australian fritillary around Port Macquarie, and for the Bathurst copper.

Indeed, most of the identified at-risk species occur across a mix of land types, including conservation, public and private land. In most cases, conservation reserves alone aren’t enough to ensure the long-term survival of the species.

Many landowners don’t realise they’re important custodians of such rare and threatened butterflies, and how important it is not to clear remaining patches of remnant native vegetation on their properties and adjoining road reserves.

People wanting to learn more about the butterfly species near them can use the free Butterflies Australia app to look up photos and information. You can also be a citizen scientist by recording and uploading sightings on the app.

Michael F. Braby, Associate Professor, Australian National University; Hayley Geyle, Research Assistant, Charles Darwin University; Jaana Dielenberg, University Fellow, Charles Darwin University; Phillip John Bell, University Associate, School of Natural Sciences, University of Tasmania; Richard V Glatz, Associate research scientist; Roger Kitching, Emeritus Professor, Griffith University, and Tim R New, Retired: Emeritus Professor in Zoology, La Trobe University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.