Sparkling dolphins swim off Australia’s coast: this is what’s threatening the natural phenomenon

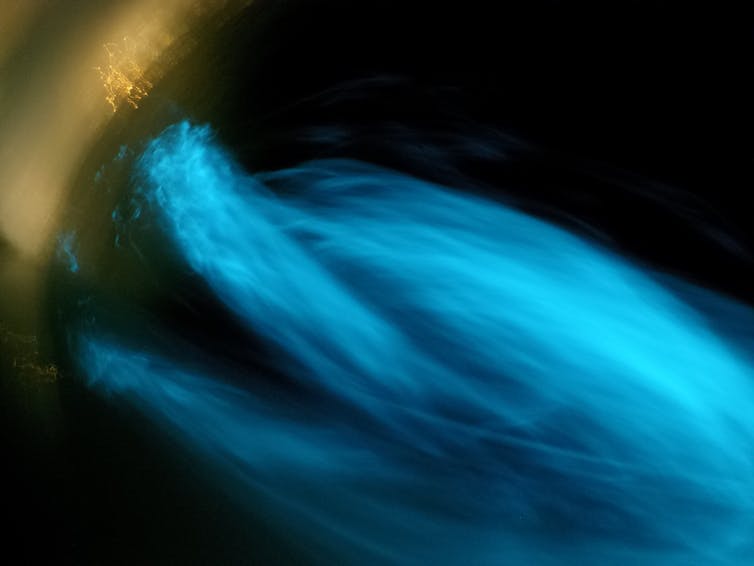

IT WAS 2 AM on a humid summer’s night on Sydney’s coast. Something in the distance caught my eye – a pod of glowing dolphins darted towards the bow of the boat. I had never seen anything like it before. They were electric blue, trailing swaths of light as they rode the bow wave.

It was a stunning example of “bioluminescence”. The phenomenon is the result of a chemical reaction in billions of single-celled organisms called dinoflagellates congregating at the sea surface. These organisms are a type of phytoplankton – tiny microscopic organisms many sea creatures eat.

Dinoflagellates switch on their bioluminescence as a warning signal to predators, but it can also be triggered when they’re disturbed in the water – in this case, by the dolphins.

You can see marine bioluminescence from land in Australia. Places like Jervis Bay and Tasmania are renowned for such spectacles.

But this dazzling night-time show is under threat. Light pollution creates brighter nights and disrupts ecological rhythms along the coast, such as breeding and feeding patterns. With so much human activity close to the shore and at sea, how much longer can we continue to enjoy this natural light show?

Lighting up the world has an ecological price

Light pollution is a well-known problem for inland ecosystems, particularly for nocturnal species.

In fact, a global study published earlier this year identified light pollution as an extinction threat to land bioluminescent species. The study surveyed firefly experts, who considered artificial light to be the second greatest threat to fireflies after habitat destruction.

At sea, artificial light pollution enters the marine environment temporarily (lights from ships and fishing activities) and permanently (coastal towns and offshore oil platforms). To make matters worse, light from cities can extend further offshore by scattering into the atmosphere and reflecting off clouds. This is known as artificial sky glow.

For organisms with circadian clocks (day-night sleep cycles), this loss of darkness can have damaging effects.

For example it can disrupt animal metabolism, which can lead to weight gain. Artificial light can also change sea turtle nesting behaviour and can disorientate turtle hatchlings when trying to get to sea, lowering their chances of survival.

It can also disorientate the foraging of fish communities; alter predatory fish behaviour (such as in Yellowfin Bream and Leatherjacks) leading to increased predation in artificial light at night; cause reproductive failure in clownfish; and change the structural composition of marine invertebrate communities.

For zooplankton – a vital species for a range of bigger animals – artificial light disrupts their “diel vertical migration”. This term refers to the movement of zooplankton from the depths of the ocean where they spend the day to reduce fish predation, rising to the surface at night to feed.

What does this mean for bioluminescent species?

Increased exposure to artificial light due to human activities, such as growing cities and increased global shipping movement, may disrupt when and where bioluminescent species hang out.

In turn, this may influence where predators move, leading to disruptions in the marine food web, potentially changing the dynamics of energy transfer efficiency between marine species.

Bioluminescence usually serves as a communication function, such as to warn off predators, attract a mate or lure prey. For many species, light pollution in the ocean may compromise this biological communication strategy.

And for light-producing organisms such as dinoflagellates, excess artificial light may reduce the effectiveness of their bioluminescence because they won’t shine as bright, potentially increasing their risk of being eaten.

A 2016 study in the Arctic revealed the critical depth where atmospheric light dims to darkness, and bioluminescence from organisms becomes dominant, was approximately 30 metres below the sea surface.

This means any change to light in the Arctic influences when marine organisms rise to the surface. If there is too much light, these organisms remain deeper for longer where it’s safe – reducing their potential feeding time.

What can we do?

Understanding the level at which artificial light penetrates the ocean is tricky, especially so when dealing with mobile sources of light pollution such as ships, which are becoming an almost permanent fixture in some areas of the ocean.

Pockets of darkness still remain in our oceans. But they are becoming rarer, making light pollution a serious global threat to marine life.

The spectacle of glowing dolphins should serve as a timely reminder of our need to conserve the darkness we have left.

Simple steps at home such as switching off lights and reducing unnecessary outdoor lighting, especially if you live near the ocean, is a step in the right direction to doing your bit for nocturnal species.![]()

Dr Vanessa Pirotta, Marine scientist and science communicator, Macquarie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.