Time is running out for these seven frog species

IN THE LATE 1970s in southeast Queensland, a silent killer arrived on Australian shores. The victims were our unique frogs, with the first to fall being the remarkable gastric brooding frog, last seen in 1981.

More than three decades on, we know that the killer was a disease called chytridiomycosis, caused by amphibian chytrid fungus.

This fungus is responsible for the presumed extinction of a further five Queensland frog species, and the decline and disappearances of many local populations across Australia’s entire east coast and tablelands, including species that were once widespread and common. Globally, hundreds of amphibian species have also suffered major declines or are now considered to be extinct as a result of this disease.

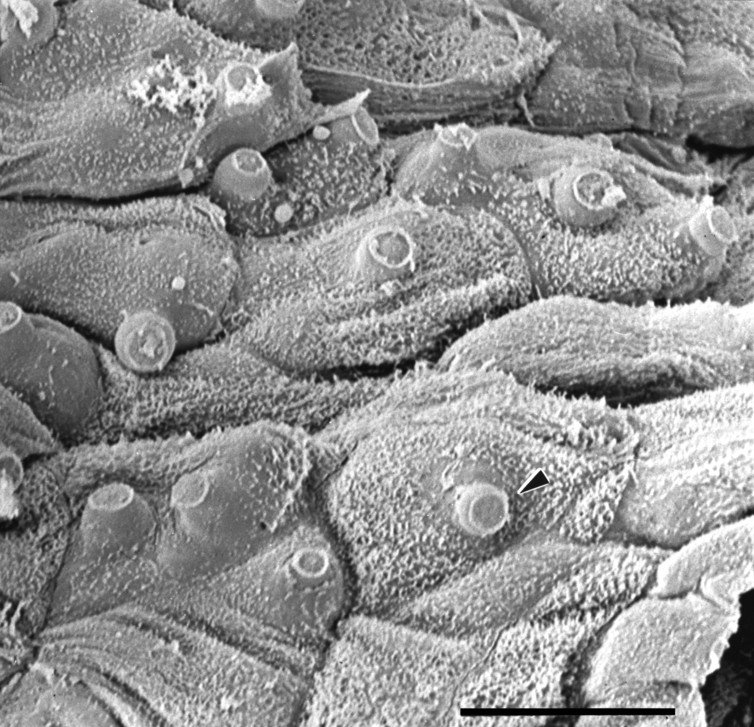

Scanning Electron Microscope image of infected frog skin with fungal tubes poking through skin surface. (Image: Lee Berger)

In a study published in Wildlife Research, we and our colleagues identify seven more Australian frogs that are at immediate risk of extinction at the hands of chytrid fungus, including the iconic Corroboree frogs (both southern and northern species), Baw Baw frog, spotted tree frog, Kroombit tinker frog, armoured mist frog and the Tasmanian tree frog. We predict that the next few years may provide the last chance to save these species.

While the six already extinct Queensland species all declined rapidly after the arrival of chytrid, declines in southern regions have been slower. Chytrid is yet to arrive in areas of Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area, although the consequences are likely to be just as severe.

- Cloning brings extinct frog back from the dead

- VIDEO: Plight of the corroboree frog

- Hot frog bodies fight deadly infection

Our work aimed to prioritise frog conservation efforts across Australia, identifying the species most at risk of chytrid, and therefore most in need of urgent action. Worryingly, we found that five of the seven high-risk species that we identified lack a sustained and adequately funded monitoring program to protect them.

In addition to the seven species at immediate risk of extinction, we identified a further 22 that are at moderate to low risk. We also assessed the adequacy of current conservation efforts for all of these species, and found that most recovery efforts rely on the goodwill of individuals and are poorly resourced.

A healthy Tasmanian tree frog. (Image: Author supplied)

It is possible to manage the threat posed by chytrid fungus, but rapid action is urgently needed. We have identified six critical management actions that are required to prevent further extinctions of Australian frogs and call for an independent management and research fund to address the imminent threat.

The seven species at high risk require proactive recovery programs. Critical management actions may include: broad-scale surveys; intensive monitoring; precise risk assessment; the development of husbandry techniques for the establishment of assurance colonies; re-introductions and or translocations; and new management strategies to maintain wild populations.

Australia initially led the world in efforts to identify and manage chytrid fungus, which was listed as a “key threatening process” by state and federal governments in 2002

In 2006, a plan was drawn up to combat the disease, delivering more research funding and resulting in greatly improved biosecurity measures and increased understanding of the fungus.

In 2012 the plan was reviewed, and a revised plan that incorporates recent research developments now awaits approval. But action is required to manage the impact of the fungus, and disappointingly there has been no funding allocated to implement the new plan.

Blink and you’ll miss them: the armoured mist frog (left) and waterfall frog. (Image: Robert Puschendorf)

The past decade has also seen major cuts in both state and federal government resources for wildlife conservation. State agencies have disbanded dedicated recovery teams and there has been a shift away from single species conservation measures in an effort to maximise limited funding. This is despite the obligations set out in legislation to conserve individual threatened species. These cuts have severely undermined frog conservation efforts.

These frogs should not be allowed to go the same way as the Christmas Island pipistrelle, which could arguably have been saved if the federal government had heeded scientists’ warnings.

On a positive note, management interventions have saved the critically endangered Southern Corroboree Frog from extinction for now, but it remains threatened by chytrid fungus and requires ongoing management and research. Without swift action, government support and the dedicated efforts of many individuals, this species would undoubtedly already be gone.

![]()

David Newell is a Lecturer at the School of Environment, Science & Engineering at Southern Cross University; Benjamin Scheele a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Ecology at James Cook University; Lee Berger is a Senior Research Fellow, James Cook University, and Lee Skerratt, Principal Research Fellow, One Health Research Group, University of Melbourne

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.