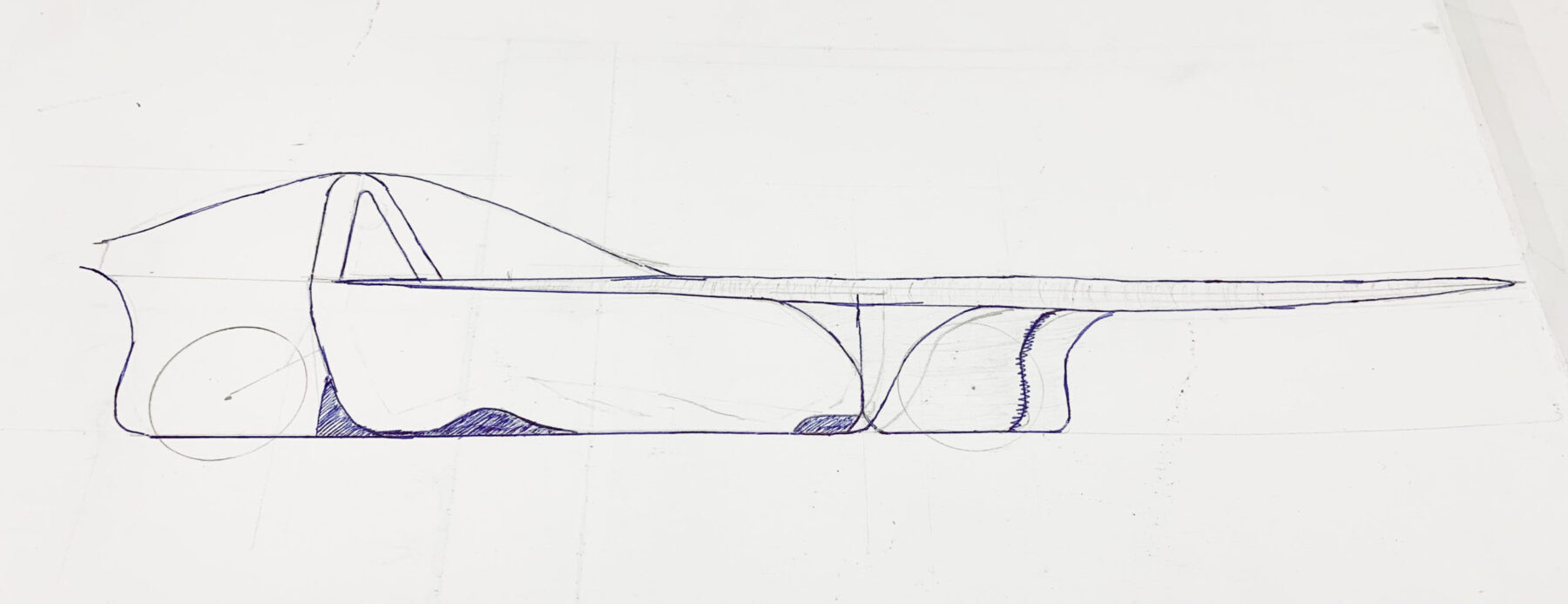

A group of students, rugged up in beanies and puffer jackets and carrying clipboards, scurries into the Engineering Building at the Australian National University (ANU), in Canberra. Deep in the bowels of the drab building is a mechanical workshop, its walls plastered with mission statements, mathematical equations and shelves of tools. Taking centre stage on the floor is what appears to be the fibreglass shell of a spaceship. Or is it a catamaran?

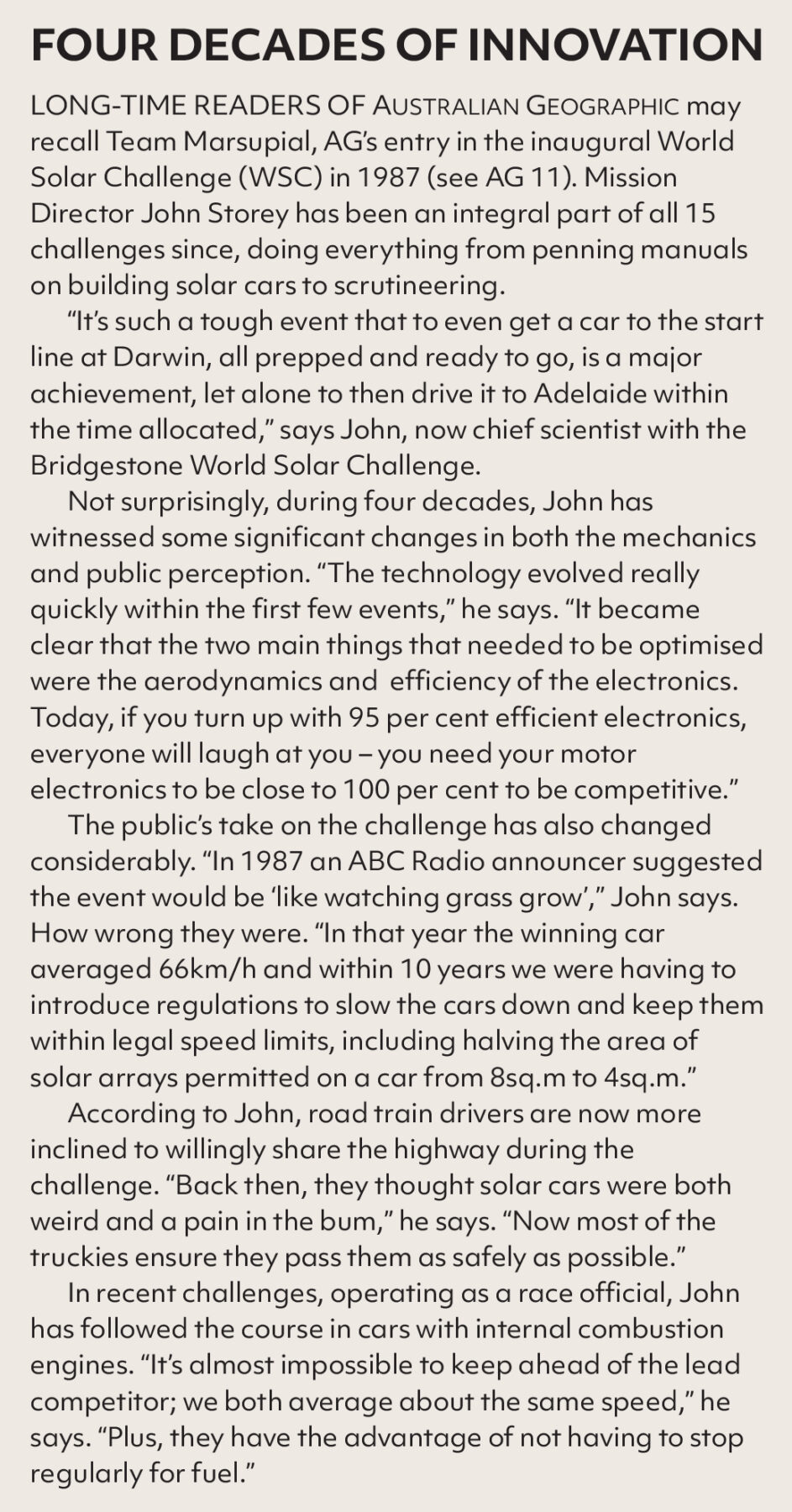

Turns out, it’s neither. It’s the chassis of Solar Spirit, a solar-powered car being constructed by the ANU Solar Racing team. It’s a frigid June evening in the nation’s capital, and this workshop seems an unlikely place to find a group of 40 students attempting to build a state-of-the-art vehicle that runs purely on energy from the sun. They’re not just driven to design and create a working car, but also to be competitive in the Bridgestone World Solar Challenge (BWSC), an event that attracts entrants from all over the world. It sees teams drive custom-made solar-powered vehicles on a gruelling 3021km journey from Darwin, in the Northern Territory, to Adelaide, in South Australia. Internationally renowned, the event has been running since 1987 and is a genuine challenge for seasoned professionals, let alone a motley mob of undergraduates assembled from each of the university’s academic colleges, not just the engineering faculty.

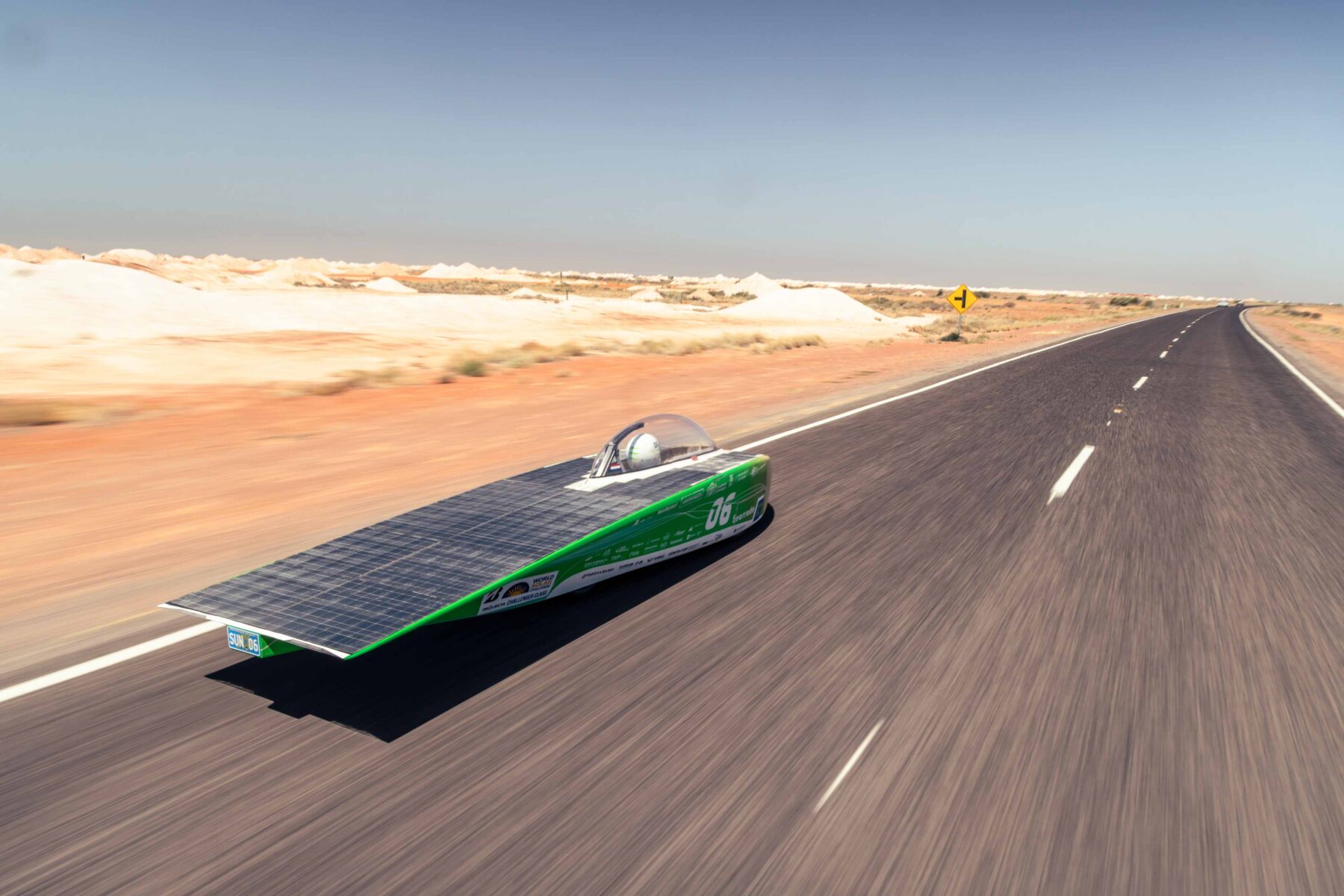

Many of the European teams that compete in the challenge enjoy multimillion-dollar budgets and are backed by internationally renowned sponsors. The event is still months away, but the German team, Team Sonnenwagen Aachen, is already testing the aerodynamics of its ultra-sleek monohulled Covestro Adelie in the Mercedes-Benz wind tunnel in Stuttgart. Rumour has it the entire car exhibits the wind resistance of a standard car’s single side mirror. Talk about stiff competition.

But what these fresh-faced students lack in financial backing and cutting-edge know-how they more than make up for in enthusiasm and dedication. While many of their peers are bingeing on Netflix, these wannabe tech heads are devoting up to 40 hours per week on top of their studies to prepare for the challenge.

“This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” says Isaac Martin, a strapping lad who’d look more at home on the basketball court than lying on his back twiddling wires under the chassis. A fourth-year engineering student specialising in renewable energy, he is the leader of the ANU Solar Racing team. It’s his job to ensure the fibreglass, tyres and wiring strewn across the workshop floor somehow make it to the start line in four months as a functioning car.

“We still have a lot to do to make it to Darwin,” he says. Talk about an understatement.

Fast-forward to 22 October 2023, and although it’s only 8am, the streets of Darwin are already lined with throngs of Territorians who’ve come to cheer on the cavalcade of futuristic-looking cars about to embark on their epic journey south. Some are sitting on their eskies, others are in their eskies.

Akin to crowds at the Tour de France, most are here for the spectacle, rather than to closely follow the fortunes of a particular team. But there is one major difference: instead of popping bottles of champagne, Darwinians are uncapping bottles of amber fluid. Yes, even at this ungodly hour.

Having qualified in pole position, Team Sonnenwagen Aachen leads the exodus out of State Square. Hot on their heels is the Innoptus Solar Team, consisting of Belgian engineering students. With no prize money up for grabs, the BWSC is officially a challenge, not a race, but try telling that to these two combatants who, along with several other European rivals, are expected to fiercely battle it out for a podium finish.

Do the inexperienced students from Canberra have what it takes to rumble with the favourites? Having passed a rigorous scrutineering session and qualified 10th on the grid during a dazzling hot lap, they’ve given themselves every chance.

“I’m just amazed they got their car to the start,” says photographer Thomas Wielecki, who has joined me for the journey south to Adelaide.

Maximising Sun exposure

More so than in most places in Australia, life in the Top End is dictated by the sun. At this time of year, most avoid the heat of the day, instead migrating en masse to the nearest air-conditioned space. And that doesn’t just apply to Homo sapiens; even the mounds of cathedral termites, which are reminiscent of elaborate medieval cathedrals and can reach up to several metres high, are aligned north–south to minimise exposure to the midday sun.

In stark contrast, solar arrays are plastered on every available surface of every entrant’s vehicle. Without exposure to the sun, there’d be no race – we’d be left to dodge crocodiles at Nightcliff Beach. While cloud cover is enemy number one, there are countless hazards the spirited drivers of these futuristic-looking vehicles need to be ready for, including those diesel-belching big bullies of the outback – road trains.

“You’d want to have your wits about you if you are sitting at ground level in a tiny 200kg solar car and a 50m-long, 200-tonne truck pulling three trailers roars past you,” says Thomas from the passenger seat of our motorhome. Then there’s roadkill. It’s at the forefront of the minds of the ANU Solar Racing team. In the last challenge, held in 2019, part of a partially decomposed kangaroo was sucked up into their car’s cockpit. Not wanting to lose precious time, they didn’t extract the putrid carcass until the next control stop 100km down the track. Eww!

Not wanting a repeat, this year ANU Solar Racing has a scout in one of its support vehicles whose main job is to look out for roadkill. They are also on watch for debris on the road and the ubiquitous cattle grids, both of which can send the solar car airborne if unexpectedly approached at the wrong angle or speed.

However, it’s not a rancid roo or a yawning pothole that rocks the ANU team less than an hour out of Darwin. The electrics on the trailer of their hired support vehicle have failed. By itself, this isn’t the end of the world. It can be readily fixed. However, when combined with a tyre blow-out on Solar Spirit, it’s a recipe for disaster. “Our equipment to fix the tyre is in our support vehicles,” Isaac says, his cursing voice crackling over the team radio.

Giving Solar Spirit every chance to catch up to us, Thomas and I pull over at the first compulsory driver-change control stop, adjacent to the abandoned Emerald Springs Roadhouse, about 190km south of Darwin. It’s here we get our first glimpse of Sunswift 7, the pride and joy of Sunswift Racing, the University of New South Wales team. They are favourites for the coveted Cruiser Class, in which participants design and create practical, multi-seater vehicles that test ideas that could one day come to market.

The control stop is like a Formula One pit stop, if it were on the set of Revenge of the Nerds. As bags of ballast (each car has a minimum weight requirement) are tossed into the gutter, each car’s new driver sprints out of a support vehicle carrying a seat under their arm. “Each seat is perfectly moulded to fit their body,” explains a race official.

While there are 23 competitors in the Challenger Class (the classic solar car class, where vehicles, including Solar Spirit, compete for the title of world’s fastest), there are just eight entries in the Cruiser Class. These cars, which look much more like standard sedans, are judged on energy efficiency, passenger kilometres travelled, and design criteria that include interior comfort, features and desirability. Most importantly, unlike the Challenger Class vehicles, which are powered 100 per cent by solar, Cruiser Class vehicles are also allowed two electrical charges along the route – one at Tennant Creek and one at Coober Pedy.

In early 2023, Sunswift 7 set a record for being the fastest electric vehicle to complete 1000km on a single charge. Elon Musk knows the vehicle by name. How could he not. If one day partially solar-powered vehicles start to appear at Tesla showrooms, this is probably what they’ll look like.

Pub talk

With Solar Spirit still floundering back in the field, Thomas and I face a difficult decision. Do we wait, or try to keep pace with the front-runners? We choose the latter, and by late afternoon, we’ve caught up to the leaders spread out along a 66km section of the Stuart Highway near Daly Waters, jostling for the best overnight camp spots.

Parched after a long day on the road, Thomas and I make a beeline for the iconic Daly Waters Pub. With the onset of the wet season imminent, it’s usually quiet at this time of year, but not tonight. It’s abuzz with chat about the race. Oops, challenge.

Perched on bar stools next to us are several “red shirts” – the nickname given to the army of volunteers who help make the BWSC run like a well-oiled machine.

“Ben Lexcen, eat your heart out!” says one red shirt, referring to the innovative, swivelling, retractable fin/sail on Infinite, the Belgian team’s car. Apparently, it’s designed to harness the crosswinds that howl across the Central Desert. And it seems just about everyone has an opinion on the fin, whether they’ve seen it or not.

“How is that even allowed?” asks a member of the bar staff.

“There’s nothing in the regulations to say you can’t use the wind,” answers Dr Thomas Schmidt. He’s one of the only thirsty patrons not in red, but he does have a close connection with one of the teams, albeit an unusual one. He designed the shoes worn by the German team. Really!

“Being able to prove sustainability credentials is important for all the European teams,” he says, adding that the shoes are made from a recycled material and coated with a bio-based resin. “The greenhouse gas emissions for each pair produced in this way are about 260g of CO₂ equivalent, less than a pair of standard shoes,” he says, concluding that while it may not sound like much, if you multiply it by 50 pairs of shoes, it makes a difference.

The pub isn’t the only distraction in Daly Waters. One of the outback outpost’s biggest claims to fame is a tree that European explorer John McDouall Stuart camped near on his third and successful attempt to reach Darwin in 1862. Apparently, he carved the initial “S” into it. While the route from Port Augusta to Darwin now bears his name, the S seems to have faded into oblivion over time. That’s if he did carve it, because there’s no mention of it in his diary.

Sunstruck onlookers

Of course, the solar car teams aren’t stopping for any sightseeing. During permitted driving times of 8am–5pm, they only stop driving for compulsory control stops, one of the few places members of the public can gawk at (but not touch) the cars up close.

Among the small posse of sunstruck onlookers at the Tennant Creek control stop is Ruth Furber. She’s feverishly snapping photos with her smartphone. “It looks so claustrophobic,” she says as the driver of the slick red-and-white car of Japan’s Kogakuin University Solar Team clambers on all fours out of the cockpit, enough sweat dripping off him to make the Todd River flow again.

Hailing from Mparntwe (Alice Springs), Ruth reveals she’s been an ardent fan of the solar challenge since its inception in 1987. “My friends down in the Alice will be so jealous that I got to see the cars first this year,” she boasts as she quickly uploads selfies onto Facebook.

The Alice is another 500km south. That’s a long way cooped up in an air-conditioned motorhome, let alone in a solar car where the cockpit temperature can soar to higher than 50°C.

Out here, the heat haze can also play tricks with your mind. It makes objects in the distance look bigger than they are, and just on sunset, we spot what appears to be six giant statues rising above the mulga beside the highway. It’s only as we get closer that we realise they’re the support crew from the Japanese team Ruth had photographed earlier in Tennant Creek. Having already set up camp for the night, they’re tilting the top of their solar car towards the sun.

I jump out for a closer look. Expecting a hello, I’m somewhat taken aback by a flurry of furious arm movements and stern words hollered in my direction. Oops, my shadow passed over their solar arrays, albeit for just a few fleeting seconds. Talk about squeezing every last bit of energy out of the sun!

Making tough calls

Further down “the track”, as many colloquially refer to the Stuart Highway, the Dutch team, Top Dutch Solar Racing, with its sleek monohulled vehicle, Green Thunder, has pitched its tents adjacent to the Barrow Creek Hotel.

You’d think 50 famished solar racers bunking down on your doorstep would be an economic boom for a far-flung roadhouse/pub, but due to the BWSC’s strict driving times, Top Dutch Solar, like all the other teams, is completely self-sufficient. It’s just a fluke that as the clock ticked over to 5pm they happened to be passing the roadhouse.

Not wanting to leave the Barrow Creek economy in an unduly suppressed state, Thomas and I poke our noses into the front bar. Rick Szoboszali, bottle of beer in one hand and half-eaten sausage in the other (apparently, it’s gourmet barbecue night at the pub), ambles over to say g’day. And while he’s not a local, he may as well be. After a couple of decades roaming from Darwin to Kalgoorlie “and everywhere in between”, salvaging wrecked or bogged cars, Rick has rightly earned the moniker “the strolling scrappy”. When work is slow, he picks up odd jobs along the way.

“I’ve been guarding the fuel pumps to make sure no-one drives off without paying,” he says. “It happens far too often here, and a full tank of diesel can be hundreds of dollars.”

Although the solar cars don’t need fuel, the support vehicles do. “And they’ve been filling up,” Rick says. “I think we will need internal combustion engines out this way for some time to come.”

While we’re chatting, my phone rings. It’s the ANU team, and the news isn’t good. They failed to reach a control stop in time. “We are out,” Isaac says, the disappointment in his voice palpable. But their outback adventure isn’t necessarily over; teams forced to retire from the challenge can continue in the non-competitive Adventure Class. “We’ll reassess overnight,” he says.

The morning’s focus

The next morning, we’re up with the pink cockatoos, but not as early as the Top Dutch who, resplendent in team kit, are huddled in a perfect circle for a sunrise briefing. Keen to gain insight into what makes them tick, we creep to within eavesdropping distance. They don’t appear to notice us. They’re too focused. Either that or they think we’re spies. When we first heard about spies, we thought it was a gee-up. But it’s true. All the top teams have spy cars that brazenly tail their rivals and report back on their speeds and strategy. Who’d have thought?

“It’s likely we won’t see another solar car all day, so we need to imagine there is a team just behind and just in front of us,” says the Top Dutch team leader to his drivers. It’s only the third day of the challenge, but already the field has spread out that far. “It’s critical we don’t lose our competitive edge,” he adds, before a procession of experts report on a range of complex technical and logistical details that would likely make Mission Control’s briefing for the 1969 Moon landing seem like child’s play.

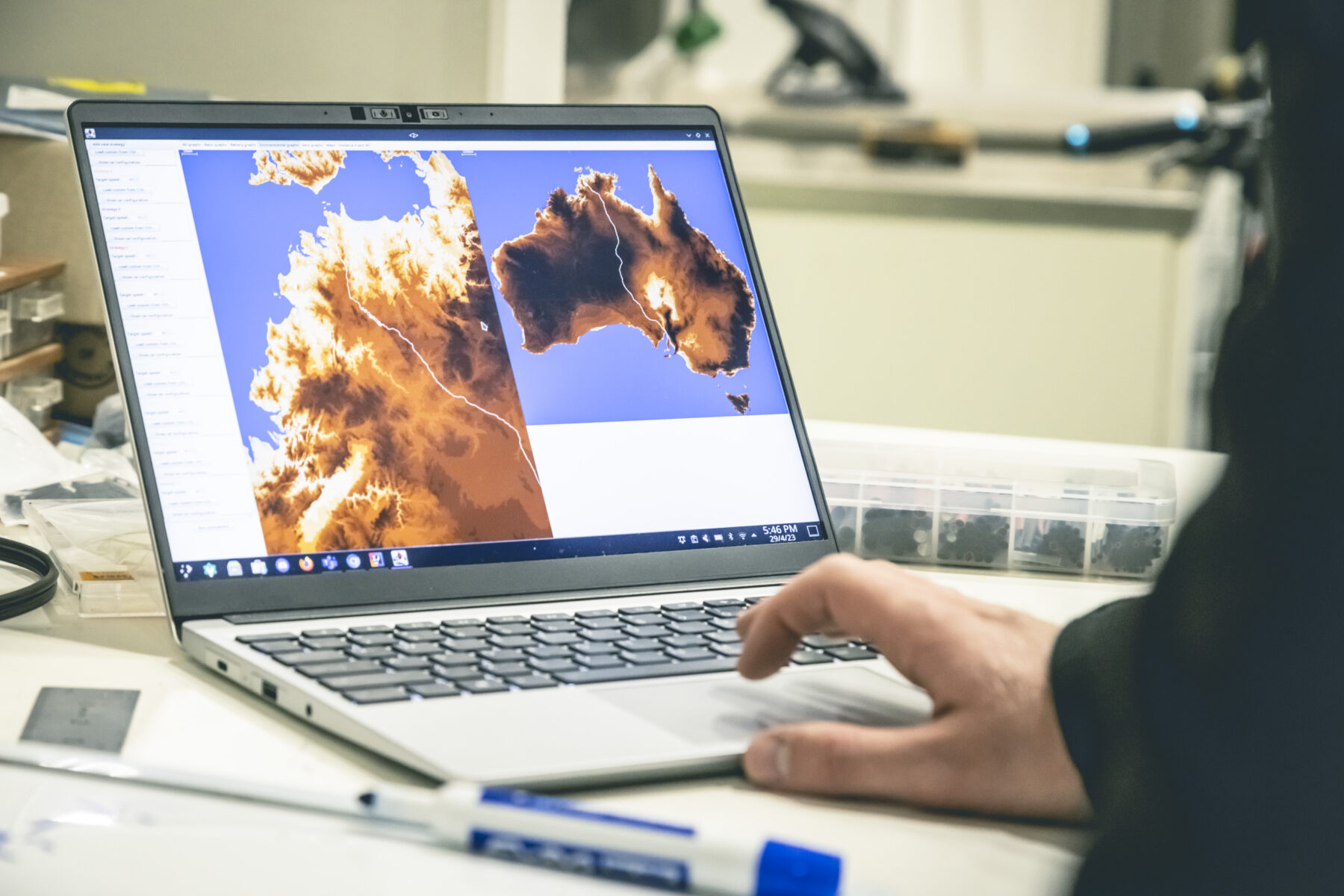

Last to step up is the team meteorologist, digital weather station in one hand, laptop in the other. “Halfway through the day a cold change will hit us,” he says.

“Aha, finally the fabled cross winds,” I whisper to Thomas.

However, the most concerning peril today isn’t the predicted wind, but rather a bushfire front burning along a 200km stretch of highway between here and the Alice. “Not only is there a chance that leaping flames will close the highway, but also that the smoke will block the sun, meaning we will lose speed,” says the meteorologist.

When Green Thunder eventually rolls back from the rest-stop bulldust and onto the bitumen of the Stuart Highway, it starts from the exact spot where it stopped the night before. The driver makes sure of it. If not, an independent observer embedded in their team would impose a time penalty, and no-one wants that.

All the colour and characters of the Australian Outback along the route cutting straight through the continent.

Outpacing a storm front

Ahead, the air is laden with thick smoke and the sides of the Stuart are blackened, but at least the road is open. For now.

Fortunately, the threat of road closures and smoke lifts as we cross the Tropic of Capricorn, travel through the Alice, and back into the wilds of the desert. Phew. We’ve dodged a bullet. Or at least we think we have.

Approaching Stuarts Well, about 90km south of Alice Springs, the sky west of us grows dark again. Only this time it’s not smoke, it’s a desert storm. Raindrops hiss and fizz as they splash onto the scorching bitumen. The temperature plummets, and, as if on cue, a mini tornado almost blows our motorhome off the road. The Top Dutch weather boffin was spot on.

“I hope the Green Thunder dodged that or they’ll end up blowing from here to Timbuktu,” I bellow to Thomas while still grappling with the steering wheel, trying to keep our overbalanced rig from toppling over.

“It wouldn’t be the first time someone came to grief along this stretch of highway,” Thomas replies.

He’s right. In May 1994 a Japanese driver and his co-driver competing in the Northern Territory Cannonball Run car race were killed instantly when their Ferrari F40 careened into a checkpoint just south of here. Two officials were also killed in the incident.

Thankfully, Green Thunder has outpaced the storm front but the driving conditions are still far from ideal. To escape the wailing westerly, we bunker down overnight at Kulgera. At the entrance to our campsite is a clothesline whizzing around with dozens of old shoes hanging from it – an outback take on the Aussie thong tree common in coastal areas. It began after a dog developed an unhealthy penchant for pilfering campers’ shoes.

“There are lots of boots, but no sign of any shoes from the German team,” Thomas says. Nor should there be; along with other race leaders, they’re several hundred kilometres ahead of us, having already crossed the SA border.

In the morning, we receive news Solar Spirit is back on the road and with the wind still howling we head for Coober Pedy, in outback SA, where we hope to reunite with the ANU team. At the pre-event briefing, we were told to watch out for outback constabulary in this part of SA. Apparently, they like to swoop on lead-footers heading from the Territory where the speed limit is higher. They’ll even book the solar cars if they’re speeding.

“A solar car pulled over by a cop – now, that would be a great photo,” says Thomas, his zoom lens already half-poked out the window looking for the money shot. Unfortunately for him, all we find patrolling the outskirts of Coober Pedy are willy-willies fuelled by dust and the broken dreams of the prospectors whose abandoned mines pockmark the desert as far as the eye can see.

Meanwhile, in town it appears as if someone forgot to circulate the memo about the solar challenge to locals. One woman trying to single-handedly change that is Sue Britt, who has hand-painted welcome messages on old pizza boxes. Some are tied to cyclone fencing at the Coober Pedy control stop but the largest of all, which screams “Go with the Sun!”, is proudly strapped to the front of her Subaru Brumby.

“Our town needs to be more welcoming to events like this,” she says. “We need to find alternate sources of energy, and solar is one of those.”

Our ponderings about future energy sources are cut short by one of the red shirts. “Here comes ANU!” he yells, as Solar Spirit arrives in a cloud of dust.

“No need for an ice vest today,” says Harrison Oates, the team’s operations manager, as driver Rachel Porter emerges from the cockpit. She smiles and, wait for it… asks for a blanket. With the mercury barely at 11°C and the wind chill in the single digits, it feels almost like a Canberra winter. No wonder Team ANU have regained their mojo.

The red shirts have breaking news. Due to a combination of smoke and strong winds, not one of the vehicles in the Cruiser Class, including the seemingly invincible Sunswift 7, have successfully finished the second stage. It’s just the second time this has happened in the history of the class.

The blustery conditions have also wreaked havoc with the Challenger field, except for the Belgian team, whose vehicle sports the futuristic fin. In fact, while we’re dodging dirt-encrusted tumbleweeds between Coober Pedy and Woomera, we hear on the race radio that the Belgians have crossed the finish line, after just over 34 hours of driving, claiming back-to-back BWSC titles. Remarkable.

Finishing without mishap

South of Port Augusta, where a maze of roadworks and lower speed limits renders overtaking near impossible, the focus for all teams turns to finishing without any mishaps. However, disaster strikes the German team when their car is blown off the highway. Their driver is lucky, escaping with a few scratches, but it’s tough luck for the team, whose car also flipped in the 2019 challenge.

It’s also far from smooth sailing for ANU Solar Racing, who come to the aid of another team after one of their support vehicles T-bars a galloping emu.

Meanwhile, in Adelaide’s Victoria Square, perched on a pedestal in the shadow of the chequered flag is the Belgian team’s winning car. Several of the team’s tech heads are showing off their car’s daring design to a crowd of captivated bystanders. “It not only made us faster, but also improved our stability,” says team manager Cedric Verlingen, after having crunched the numbers on the impact of that fin.

In contrast, hidden in the marquee on the far side of the square, Niklas Taphorn, electrical engineer with retired rival Sonnenwagen Aachen, cuts a lonely figure as he stands forlornly over his team’s patched-up entry. He recalls the incident that forced his team to bow out of the event. “It’s all a blur, but two road trains passing in either direction created a vortex, flipping the car,” he says, revealing that the rest of his team are licking their wounds, enjoying some saltwater therapy at Glenelg Beach. “We’re devastated,” he says, “but we’ll be back even faster for the next race.”

A raucous cheer erupts as ANU’s Solar Spirit crosses the finish line. Supporters have travelled in numbers across the Hay Plain from Canberra to see their family and friends reach the end.

I’d like to report that the loudest applause is from their biggest fans, but Thomas and I are exhausted. We travelled and camped in air-conditioned luxury, and we can barely rustle up enough energy to clap. I can only imagine how Isaac and the team must feel.

“It really is a life-changing experience,” Isaac says. “In the face of adversity, we’ve bonded incredibly well as a team and have learnt so much,” he adds, appearing to wipe something out of the corner of his left eye.

“Are they tears?” asks Thomas.

“No, it’s just a speck of dust from the Central Desert,” I reply.

Of course, it’s probably both.

The Bridgestone World Solar Challenge is a biennial event. The next challenge is scheduled for October 2025. Find updates at worldsolarchallenge.org/