Do you collect souvenirs when you travel? If you’re anything like me you have shelf after shelf of mementos from your sojourns in all shapes and sizes – some novel, some deeply sentimental, and some very expensive.

But does your collection include tortoiseshell products?

This is the question WWF-Australia recently asked Australians as part of the conservation organisation’s Surrender Your Shell campaign.

Not only did they put the call out, wanting to know if anyone had any of these products, but also asked for the souvenirs to be handed over, never to be returned.

“Some of these are highly valuable and prized items,” says Christine Madden Hof, WWF-Australia’s global marine turtle conservation lead.

“We got hundreds of items donated. We are really grateful for the willingness of the community in Australia to help.”

The Surrender Your Shell campaign offered an amnesty of sorts, an opportunity for members of the public to hand in these products, without fear of repercussion.

Because, you see, although tortoiseshell merchandise is available to be purchased all around the world, it is, in fact, illegal to possess it in many countries, including Australia.

“The Australian Government supported [the Surrender Your Shell project] by giving the opportunity for Australians to do so without risk of being prosecuted,” explains Christine.

The possession of tortoiseshell products has been illegal in Australia – and in every country signatory to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) – since 1977.

But it gets confusing. Laws do differ between countries, making distinguishing between what’s legal and illegal can be a minefield for international travellers.

“For example, in a country where hawksbill turtles are not protected by legislation, it may be legal to purchase tortoiseshell products, and if [the purchase] was to stay in that country – that may be seen as ok. But it would be illegal to take it across international waters to another country, which is signatory to CITES, explains Christine.

“This is the problem we are facing with conserving hawksbill populations targeted in this way – some countries have more relaxed legislation than others.”

Hawksbills hunted to the brink of extinction

There are seven surviving species of sea turtle in the world, six of which occur in Australian waters. All are targeted in various ways by illegal traders.

But the hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) is the species most exploited for its shell, which has overlapping scales that create a serrated edge on the carapace. This is the famous, and coveted, “tortoiseshell” that’s so well known and that gives the material its unique appearance.

Some other marine turtle species also have this shell pattern, but, as Christine explains, hawksbills are the only turtles widely used for making tortoiseshell products.

“It is the only turtle species that tortoiseshell products can reliably be made from,” she says.

“There is some evidence of green turtle tortoiseshell products, but the shell is very thin, it’s very difficult to work with, so it’s mostly hawksbills that are used.”

This ‘popularity’ has driven the hawksbill to the brink of extinction.

Listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, maintained by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, WWF-Australia estimates that in the past 150 years almost nine million hawksbill sea turtles have been hunted and killed across the Asia-Pacific region.

Despite international trade bans, this poaching continues today. And detecting trafficking has become even harder.

“[Since the bans] you don’t see hawksbill turtles or marine turtles on the top of fishing boats anymore, or being transported openly in cargo ships. It’s much more of an underground, covert operation,” says Christine.

Christine and her colleagues began discussing ways to help authorities track and dismantle this illegal trade. Following a series of brainstorming sessions, they came up with the idea of ShellBank.

“We see this as a game-changer,” she says.

How ShellBank works

Seizing a tortoiseshell product is one thing, but knowing the original poaching location of the turtle it came from is another.

The problem facing law enforcement and conservation agencies is that to catch these criminals in the act, they need to know where to look and in what regions to focus scarce resources.

This is where ShellBank can help. Put simply, it is a global ‘bank’ of seized or donated tortoiseshell products.

While initially established by WWF in 2018, it is contributed to by multiple organisations and governments around the world.

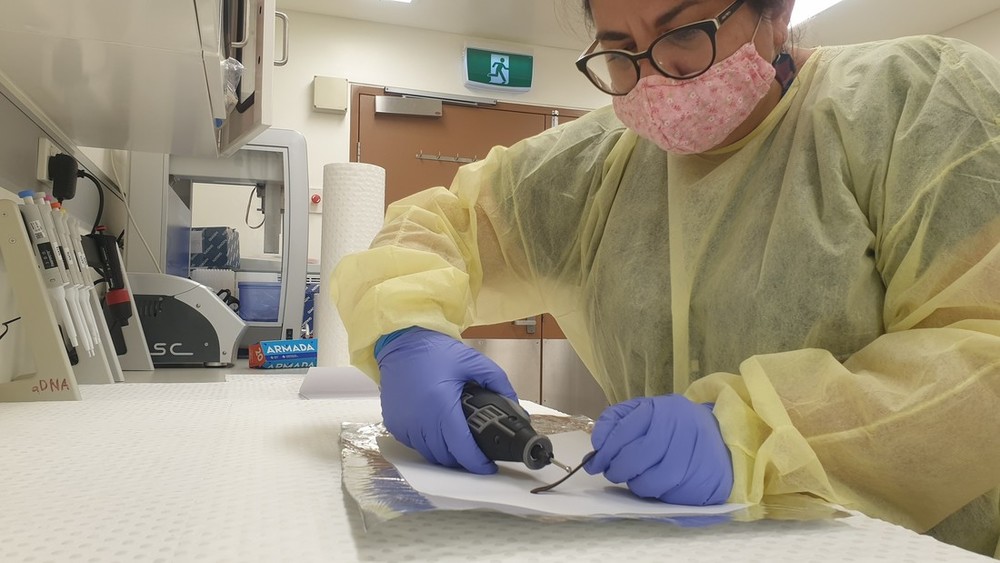

The idea is that DNA can be extracted from each illegal product to find out where the turtle it came from was hunted.

This is done by comparing the extracted DNA to another database of DNA, collected from individual hawksbill nesting populations and foraging regions across the globe.

“To be able to trace a tortoiseshell product back to its source we have to rely on the source information of populations, which relies on us being able to sample the wild hawksbill populations and have a reference database and a bank of data that tells us where these turtle populations nest, where they feed, where they migrate,” explains Christine. “That’s how we get ShellBank to work.

“We still have some pretty big gaps in our reference database, but in saying that we are now ready to start gearing it up for uptake across Asia-Pacific because the more we work with different countries, different researchers, we’ll keep filling those gaps.”

Dr Greta Frankham, a certified wildlife forensic scientist at the Australian Museum Research Institute, who extracts the DNA, says as these gaps are filled, ShellBank has the potential to be the ‘game-changer’ Christine hopes it will be.

“As ShellBank expands, the DNA testing of seized items will lead authorities to where poaching is rampant and hawksbills are under the most pressure. We hope that can be a turning point in saving this species.”

What did the surrendered products tell us?

The Surrender Your Shell campaign resulted in Australians handing in 220 items, wildlife trade-monitoring network TRAFFIC donating 101 items, and the Australian government contributing seven items.

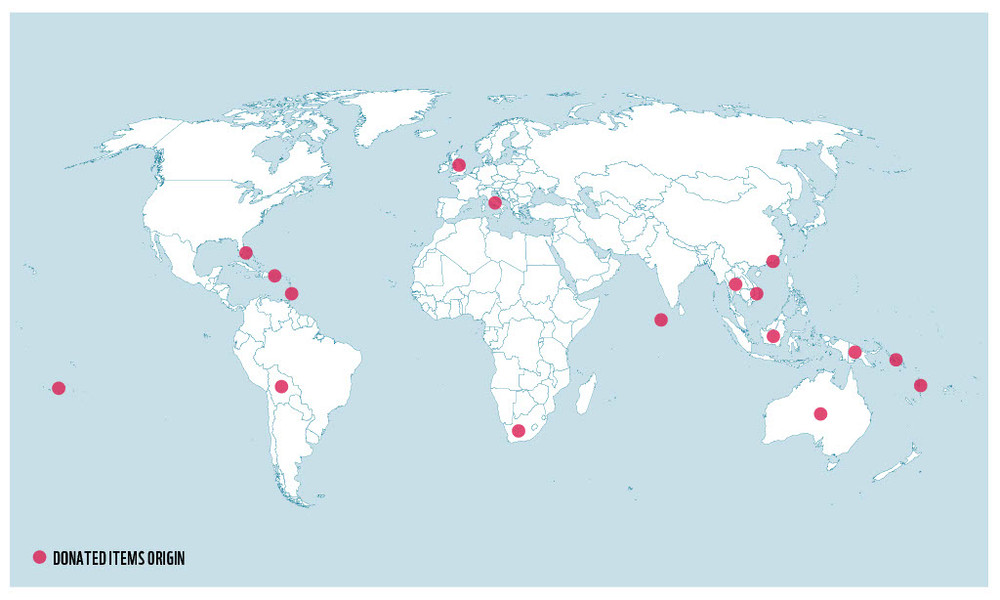

The items included hair accessories, jewellery, bookmarks, salad servers, scutes (part of a turtle shell), and 19 whole shells, purchased across a geographical spread including Italy, the Bahamas, St. Lucia, Puerto Rico, Bolivia, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Fiji, Solomon Islands, other unspecified South Pacific islands, Australia, South Africa, the Maldives, Thailand, Vietnam, Timor Leste and Hong Kong.

DNA was extracted from these donated products at the Australian Museum Research Institute’s Australian Centre for Wildlife Genomics (ACWG), Australia’s only accredited DNA-based wildlife forensic laboratory.

According to the report, the testing found “57.9% (190) of the items were made from hawksbill turtles, 29.6% (97) were plastic, 0.6% (2) were from tortoise species and, surprisingly, 11.9% (39) were made from green sea turtles (after it being assumed their shell was too thin to be processed into tortoiseshell products).”

The DNA from the hawksbill products was then checked against ShellBank.

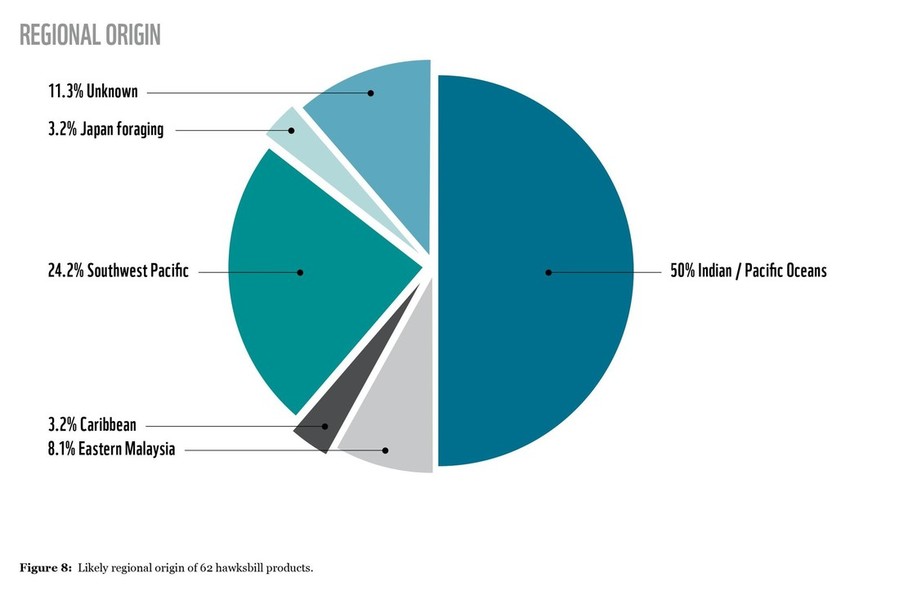

“Of the 62 hawksbill products successfully sequenced, DNA indicated 3.2% were likely from Japan (foraging area not nesting beaches), 3.2% Caribbean, 8.1% Eastern Malaysia, 11.3% unknown, 24.2% Southwest Pacific, and 50% had genetic variants common across the Indian and Pacific oceans,” the report reads.

Raising awareness

Twenty of the tortoiseshell items donated by members of the public were purchased after 1977. This is after the CITES ban on the international trade of hawksbill turtles and products.

This indicates that many Australians remain unaware that possessing these products is illegal.

Christine says she has noticed through her work that many people also have a disconnect between the items and where they come from:

“Time and time again we got comments like ‘Oh, I didn’t know that marine turtles were still harvested, nor did I know, or did I connect the dots, that this tortoiseshell product came from a live, swimming, beautiful creature…’ I get this feedback from the public whenever I talk about the project – a lack of awareness.”

Christine Robinson, who donated a tortoiseshell bracelet to the Surrender Your Shell project, says she had no idea the piece of jewellery she purchased was made from a hawksbill turtle shell.

“When I chose the bracelet I was totally unaware of the tortoiseshell trade,” says Christine. “To me it was just an attractive object. It didn’t cross my mind it could be real tortoiseshell, and made from a beautiful and critically endangered animal.”

She says she is now a much more discerning shopper, and wants to spread the word.

“It’s important to think before you buy on your next shopping excursion or overseas holiday. Avoid jewellery or souvenirs that look to be made of tortoiseshell. There’s only one place that tortoiseshell belongs – and that’s on the back of living turtles.”