Scientists spot a cluster of bigfin squids in Australian waters for the first time

FOR THE FIRST time ever, Australian scientists have spotted the bigfin squid in Australian waters.

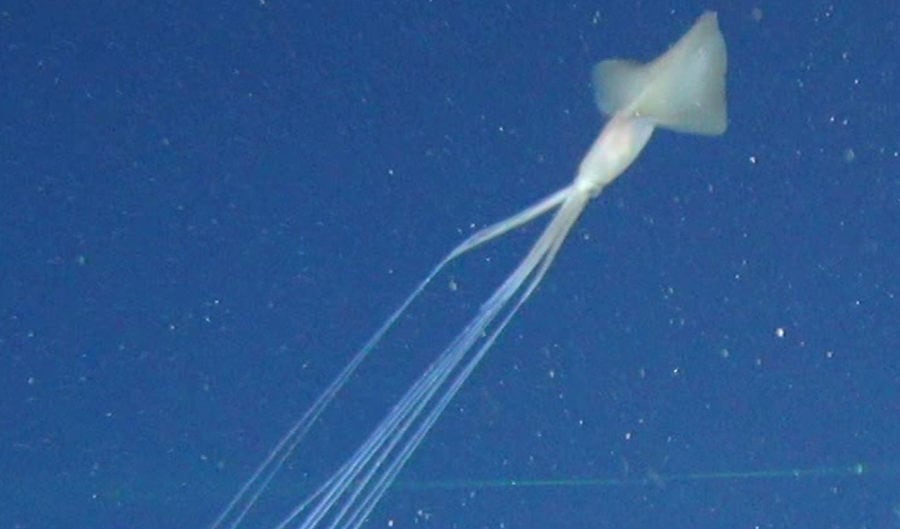

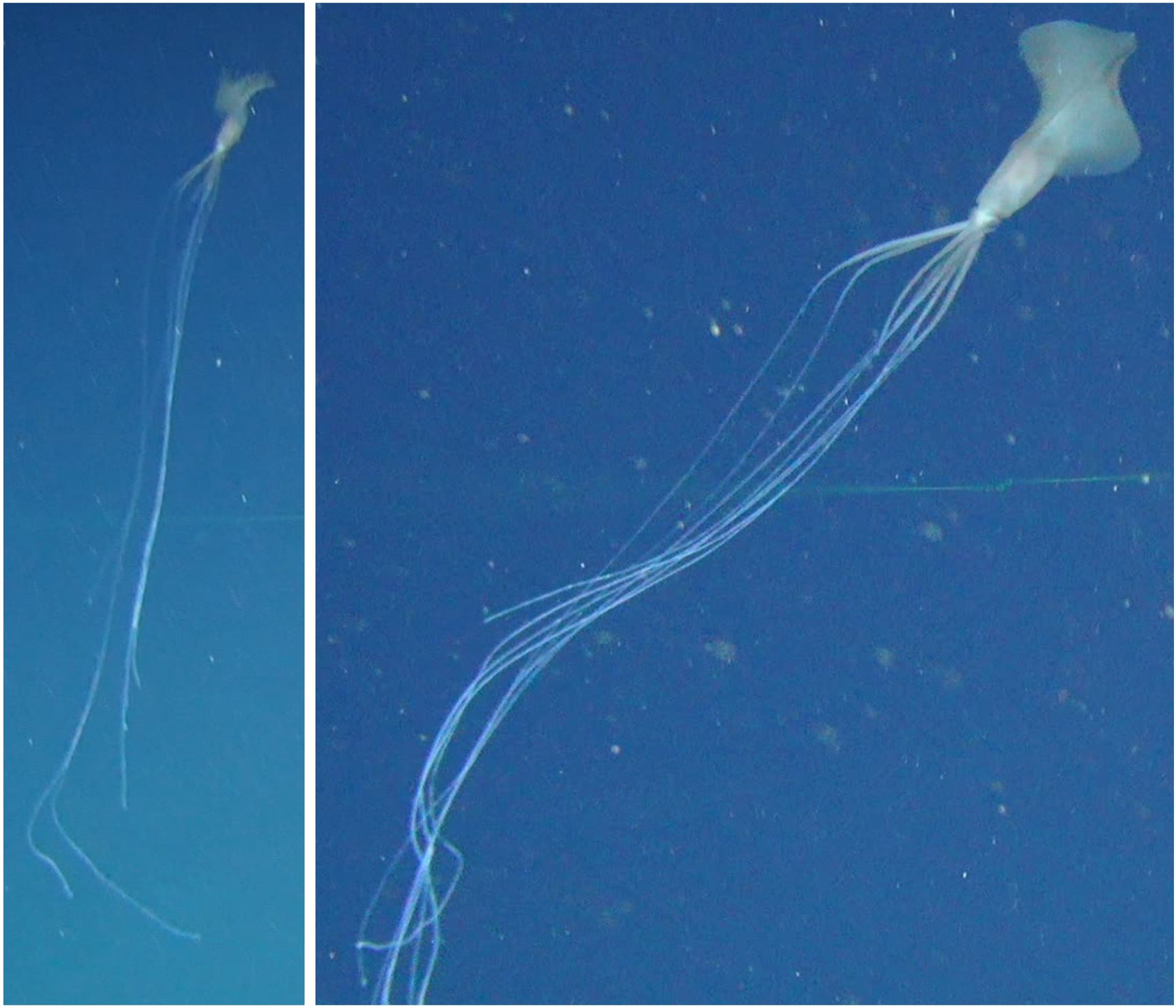

The deep-sea animal is known for its long tentacles and large fins, which sets it apart from its squid relatives.

Five individual squids were photographed in the Great Australian Bight during two deep sea voyages.

“Five sightings in the Great Australian Bight is definitely a considerable number given previous observations of the family total around a dozen globally, over 30 years,” says marine scientist Deborah Osterhage, who first identified the squids.

“Very few have been seen in the southern hemisphere until now, but it had been hypothesised they had a cosmopolitan distribution. Our sightings bolster that hypothesis.”

According to Deborah, it’s highly unusual that the squids were seen so close together.

“Often such clustering can be associated with specific environmental needs or increased reproductive opportunities. Hopefully future sightings will help us answer why they were in close proximity.”

Previously, to measure the squids, scientists had to estimate their size based on nearby objects, but this time lasers were projected onto the body of the squid to provide a more accurate scaling of size.

The total length was more than 1.8m, which Deborah says is longer than previous size estimates in the southern hemisphere and shorter than previous size estimates in the northern hemisphere, which range from 2.25–7m.

The scientists also witnessed some unusual behaviours, including a horizontal elbow pose (holding their tentacles out at sharp right angles) and a single raised arm during upwards movement, behaviours which have never been observed in squids.The squids were also seen reeling in their long tentacles, coiling them up so that the filaments weren’t dragging behind as the squids swam through the water.

The bigfin squid is one of many new discoveries made by the deep-sea voyages conducted by CSIRO. Observing deep-sea animals such as the bigfin squid, which in this case was observed up to 3km below the ocean’s surface, can be difficult.

“It can be costly arranging ocean voyages and using specialised equipment to reach such depths or withstand the pressure down there,” Deborah says, which is why only five per cent of the deep sea has actually been explored.

That the bigfin squid has a soft body makes it all the more difficult. “When trawls are used in deep-sea surveys they can damage soft-bodied squid specimens to the point that some mangled specimens offer very little information.” But ROVs (remotely operated vehicles) are offering new opportunities for marine scientists such as Deborah, and there’s still plenty to find out about the bigfin squid.

“Basic questions such as what it feeds upon, how it reproduces, are still unknown,” she says.

“An intact adult specimen has never been collected, so each sighting is important in contributing to our knowledge.

“Future sightings should try to gather as much information as possible from their imagery – descriptions of surrounding habitat, colouration, behaviour, morphological information – so that we can gain a better understanding of these amazing animals.”