Located in the Coral Sea off the Queensland coast is the largest living structure in the world.

It’s one of Earth’s most complex natural systems, home to countless animals. And to the rest of the world it’s one of the most identifiably Australian places. We all know what it is – the Great Barrier Reef (GBR)– and that it’s under pressure. But how can we frame its intricate natural architecture in a new way that inspires people to love it enough to care about its future?

That was the question passionate Townsville-based marine scientists Dr Adam Smith and Dr Paul Marshall were struggling with when they attended a talk by a fellow scientist discussing an underwater art installation on a reef in Cancun, Mexico.

It turned out to be a watershed moment.

“Like all good ideas,” Adam says, “the seeds stem from somewhere else. I listened to this scientist talk about what had been done on a reef in Mexico and thought what a perfect fit this concept would be for Townsville.

“We are a reef city, with the GBR on our doorstep, but many people don’t even realise this. We are the hub for scientific reef research and our city has a gathering of great minds studying our oceans and reef at James Cook University.

“We have the world’s largest living aquarium on display, but tourists still tend to link Cairns with the GBR, not Townsville. We needed to come up with something that was going to shine a light on the science and culture of our reef here. And it needed to be thought-provoking on a global scale.”

The idea of underwater art installations located off the north Queensland coast was hatched. And this year, four years later, the Museum of Underwater Art (MOUA) launched its first huge in-situ artwork on John Brewer Reef, 70km off the coast from Townsville.

“You know the saying, ‘It takes a village to raise a child’?” Adam asks. “Well, it has taken a city to get MOUA installed. So many extraordinary people, companies, private businesses and government departments have pulled together to be involved, supplying their time, expertise and funding to make this happen.”

The installation on Brewer’s is the first of three. Others are planned for Magnetic Island, also off the Townsville coast, and Palm Island, further north.

“But of course we are enormously proud and excited about the opening of this first installation. It’s a world-class experience,” says Adam, who is deputy chair of the MOUA board and owner of Reef Ecologic, a Townsville-based company that provides advice, research and training on issues facing coral reefs.

The MOUA team felt it was vital that the project attract a world-renowned artist, to bring it global attention. “So with little or no budget, we contacted the best of the best – UK sculptor Jason deCaires Taylor, who has previously been involved in underwater sculptures across the Northern Hemisphere.”

But how to attract him to the project with no money? “So we invited him to stay in our homes,” Adam recalls, explaining that Jason was embraced like a family member by the project team.

“We shared meals, took him diving and found out he is a particularly good squash player.” The strategy worked and Jason agreed to the project. Many meetings and much planning and collaboration followed during the next four years. “There needed to be strong vision for this project and the conversations with Jason were long and ongoing,” Adam says.

Jason’s willingness to take on a challenging project on the other side of the world is evidence of his passion for art and conservation. Born in the UK, he graduated in 1998 from the London Institute of Arts with an honours degree in sculpture.

He’s also a fully qualified diving instructor – trained in Queensland – and a naturalist and talented underwater photographer.

The vision for MOUA is to provide a submerged experience that inspires reef conservation and engages the community in cultural land and sea stories. Jason achieves that with a Coral Greenhouse idea that melds humanity and the reef, both metaphorically and figuratively. Jason’s installation features life-like statues, cast using real people, to give life and breath to the reef itself, connecting art, science, culture and conservation.

I’m lucky enough to be on Yongala Dives’ inaugural dive trip to the site. As the sun rises, we leave Townsville for the two-hour voyage to John Brewer Reef. There is an air of anticipation among those on board. Owner and skipper of Yongala Dive, Matt King, is clearly excited to be able to offer visitors to Townsville a new experience.

“This is something different from anything else around,” he says. “Our company dives the famous Yongala wreck every day, so I’m very spoilt. But as far as a dive site goes, this doesn’t have to be the most fantastic fishy site in the world – this site is going to attract people because it’s so different.” In time, the site’s structures will become covered in coral, and fish will make them their homes.

“The concept is to bring more people to the reef and region by raising awareness about the reef,” Matt explains.

“Hopefully, they will also learn things they didn’t know, taking home ways in which they personally can have a positive impact on [the reef’s] preservation. It’s a great idea for sure. It’s a trip for everyone, not just divers. Bring Grandma. Surrounding MOUA is this fabulous healthy reef, covered in magnificent plate coral that snorkellers also will love and enjoy.”

Also on board is Richard Woodgett, the underwater videographer employed by artist Jason to document the entire installation process, which took 10 days of living and working out on the reef. The fabrication of the structures took more than nine months in a Townsville warehouse.

Richard describes the operation as highly organised and running entirely to plan. “Initially, the installation process kept getting delayed because of weather.

The ocean needed to be like glass, but eventually they picked their window well. The greenhouse and statues were loaded onto a barge and towed by a tug, very, very slowly, to the selected site on the reef.” There were 15 construction crew and four commercial divers, who had full communication with the surface. Bit by bit, it went in.

Jason’s statues are all made of porous, pH-neutral concrete, which is not harmful to anything alive in the marine environment. In fact, the concrete, complete with little holes promoting animal lodgings, encourages coral growth, and, in time, will capture spawning coral from the nearby reef. It is envisaged that coral transplanting will also begin once permits and approvals are in place.

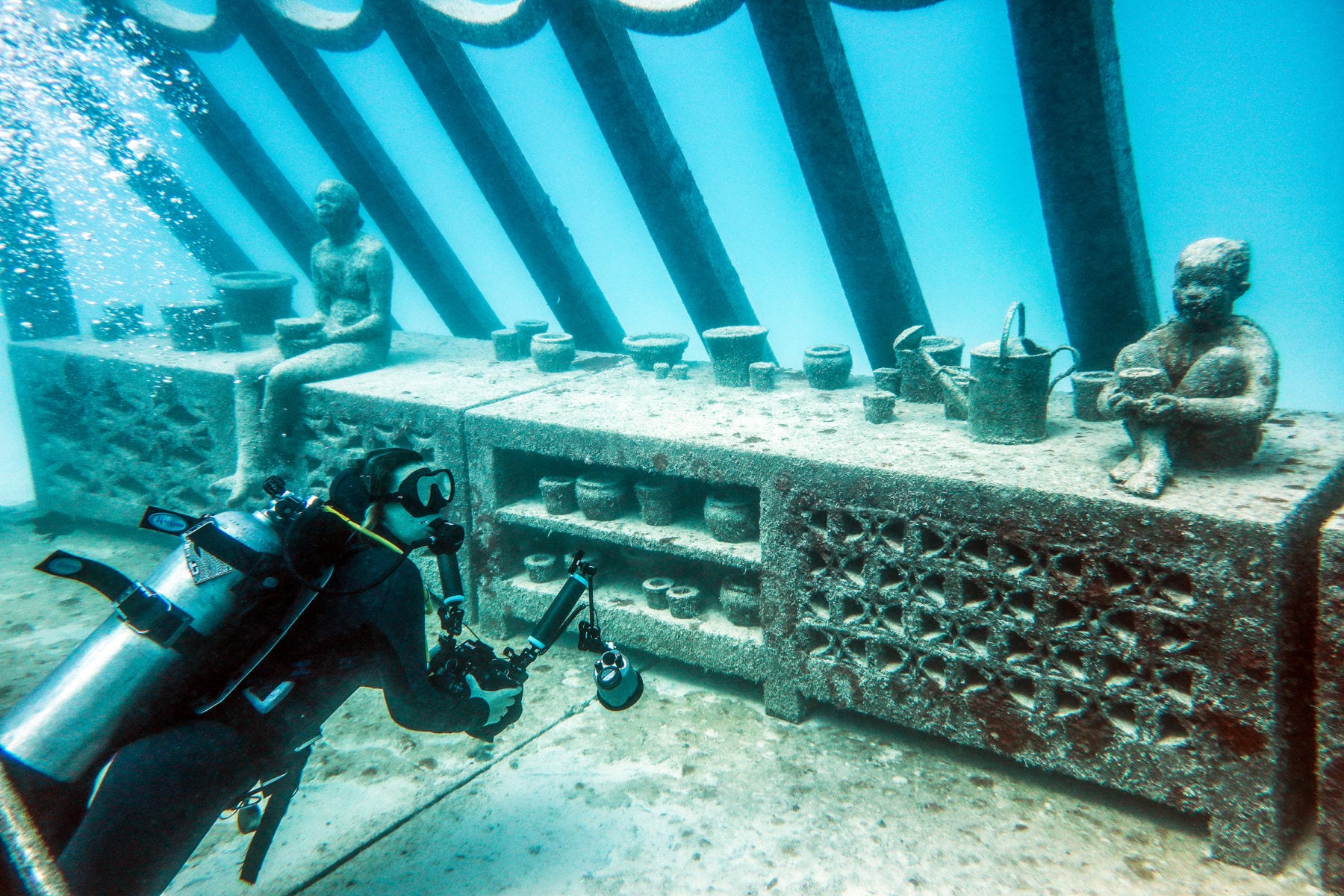

To top off this complex construction task, the frame of the Coral Greenhouse, made of corrosion-resistant Grade 316 stainless steel, weighing 58 tonnes, and measuring 12m x 9m x 6m, was lowered and attached to a substantial concrete flooring. Mirroring a terrestrial greenhouse, where plants are propagated, this underwater structure sits some 16m down on the seabed, encouraging propagation of both corals and sea life and surrounded by 25 sculptures of various objects and human forms.

It is time to see it for myself. Diving down to 16m, we make our way towards the outline of the greenhouse roof, rising through the blue. Sunlight dances on the fringes of floating umbrella palm sculptures as I swim through the A-frame opening of the greenhouse to be met, instantly, by Kevin the cuttlefish. Kevin is not a statue. Named by pre-opening divers, he’s a real-life spectacular marine mollusc who has taken up early residence in one of the greenhouse’s hanging baskets.

Kevin willingly encourages my own lingering fascination with cuttlefish, then turns his large googly eyes towards me one last time before extending his waving arms, gliding off, switching colours with electrifying speed and leaving me alone in this larger scale magnetic scene of beauty and intrigue. Then I turn my attention to Margaret.

She’s a life-sized Reef Guardian, bowing pensively over her microscope, already covered in algae, and attracting fish life that weaves about her features.

Margaret Chong is Jason’s muse for this statue, a proud Gangalidda woman from the outback community of Doomadgee, Queensland. She is one of eight human statues tending the reef, building a new relationship with a frail habitat in dire need of protection. I swim slowly from one statue to another, feeling the life they already radiate, entombed in time here, beneath the waves.

One small boy holds a planter pot. Another wields garden scissors. Creeping up the hip of a small girl, hair pulled back in a ponytail and sitting cross-legged beside a watering can, a sea star uses its hundreds of tiny tubular feet to explore its new surroundings.

With the coming and going of a school of barracuda, the atmosphere of this structure changes as it does when different fish species come and go through its unconstrained design. It has been built to withstand waves and a category four cyclone.

I vow to return annually after this dive, to watch with intrigue the story of its growth. “I am making these inert objects, but the environment is giving them souls,” Jason explains. “This is one of the most ambitious artworks I have ever created. It is a portal, or interface, if you like, into our underwater world, for people to understand what a beautiful and sacred space it really is.”

The GBR can teach us about the interconnectedness of all life. It is up to each of us to implement small changes into our daily lives, to ensure our reefs are here for our children and for the benefit of future generations. It was empowering to see statues cast on real children. These will act as beacons in time, mapping coral growth and drawing in more hearts to care about the health of our reefs.

Back on Townsville’s foreshore I visit another arm of the installation – Ocean Siren – a 4m-high sculpture modelled on Takoda Johnson, a young member of the Wulgurukaba tribe.

Ocean Siren is linked to a live feed from a weather station on nearby Davies Reef. Her 202 multi-coloured LED lights change colour depending on the surrounding sea temperature, potentially warning of warming seas and risks to coral reefs. It is another clever, visually emotive, way to highlight the needs of our oceans.

“It is very exciting,” Takoda says. “Ocean Siren is looking out onto the ocean and reef like my people have done for thousands of years. It is a great honour for me. When I was younger my great-great-grandad would always paint these beautiful paintings and tell us stories of how we always need to respect and look after the ocean. I didn’t really understand. But now that I’m older I feel like we need to think about what we’re doing to the ocean and how we’re impacting it.”

Ocean Siren looks over the ocean to Magnetic Island and beyond, holding a baler shell, a link to the ocean that has been used to blow messages to her people for millennia. MOUA holds an important message for us all as a meeting place of art, tourism and marine science – a beacon of light and life, for the reef, and its future.