We’re in for yet another hotter and drier than average summer

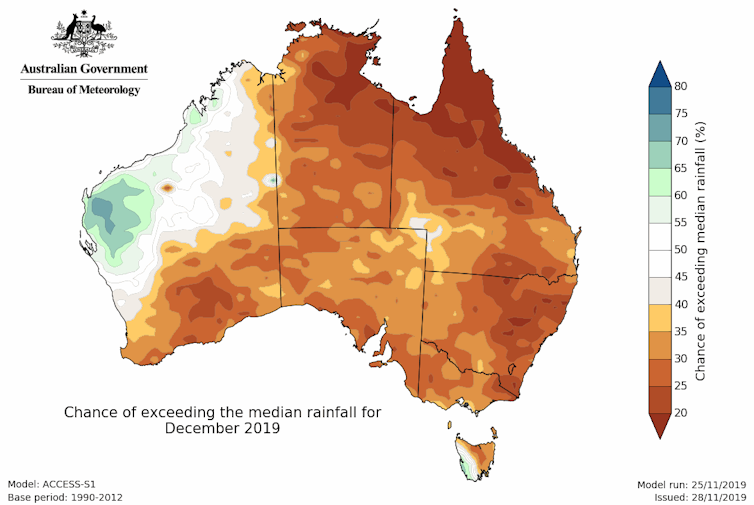

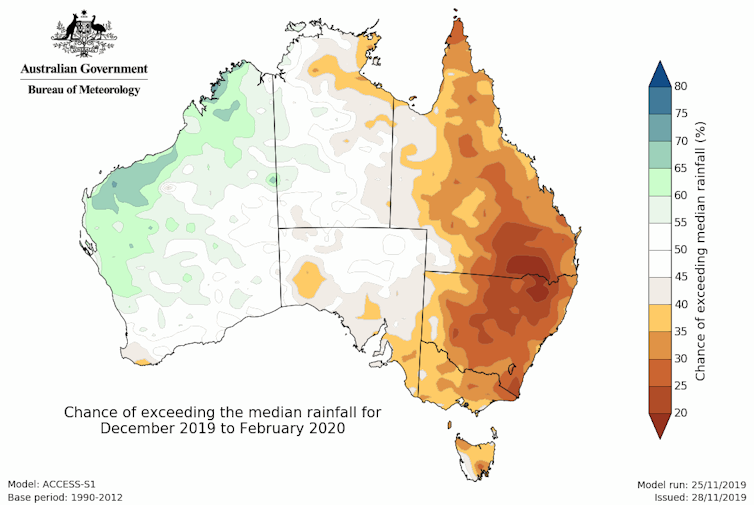

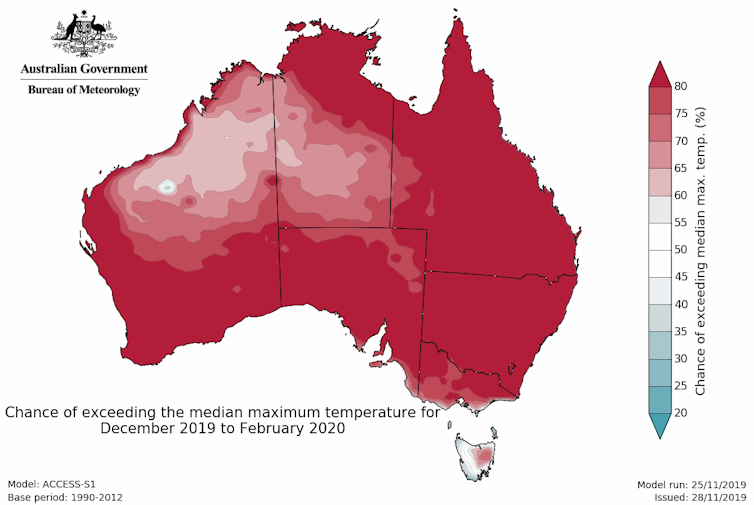

Much of eastern Australia is likely to be hotter and drier than average, driven by the same climate influences that gave us a warmer and drier than average spring.

But these patterns will break down over summer, meaning these conditions may ease for some areas in the second half of the season. Despite this, we’re still likely to see more fires, heatwaves, and dust across eastern Australia in the coming months.

What drove the climate in 2019

Our current weather comes in the context of a changing climate, which is driving a drying trend across southern Australia and general warming across the country.

In southern Australia, rain during the April to October “cool season” is crucial to fill dams and grow crops and pasture. However, like 17 of the previous 20 cool seasons, 2019 was well below average, meaning a dry landscape leading into the summer months.

The frequency of high temperatures has also increased at all times of year, with the greatest increase in spring.

But summer, like spring, will also be influenced by two other significant climate drivers: a change in ocean temperatures in the Indian Ocean, and warm winds above Antarctica pushing our weather systems north.

Indian Ocean

The first driver is a near-record strong positive Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD). A positive IOD occurs when warmer than average water develops near the Horn of Africa, and cooler waters emerge off Indonesia.

This pattern draws moisture towards Africa – where in recent weeks they have seen flooding and landslides – and produces higher pressures over central and southern Australia. This means less rain for Australia in winter and spring.

Usually the IOD events break down by early summer, when the monsoon arrives in the southern hemisphere. However, this year the monsoon has been very sluggish moving south – in fact it was the latest retreat on record from India – and international climate models suggests the positive IOD may not end until January.

Southern Ocean

The other unusually persistent climate driver is a negative Southern Annular Mode (SAM), which means weather systems over the Southern Ocean – the fronts and lows and wild winds – are further north than usual. This means more days of westerly winds for Australia.

In western Tasmania, where those winds are coming off the ocean, it means cooler and wetter weather. In contrast, in southeast Queensland and New South Wales, where westerlies blow across long fetches of land, this air is dry and hot.

This persistent period of negative SAM in 2019 was triggered by a sudden warming of the stratosphere above Antarctica – a rare event identified in early September.

Models suggest the negative SAM will decay in December. This means the second half of summer is less likely to be influenced by as many periods of these strong westerlies.

But while both these dry climate drivers are expected to be gone by midsummer, their legacy will take some time to fade.

The positive IOD and the dry conditions we have seen in winter and spring are associated with severe fire seasons for southeast Australia in the following summer.

And while the drying influences are likely to ease, the temperature outlook indicates that days are very likely to remain warmer than average.

We also know that any delay in the monsoon will keep air drier for longer across Australia, and potentially aid in heating up the continent.

What about the wet season?

For areas of southern Queensland and northeastern NSW, the wet season will eventually bring seasonal rains, although heatwaves are likely to continue through summer.

So, while the outlook for below average rainfall may ease over summer months for some areas, the lead-up to summer means Australia’s landscape is already very dry. Even a normal summer in the south will mean little easing of the dry until at least autumn.

With dry and hot conditions looking likely this summer, it’s important to stay safe, have an emergency plan in place, look after your friends and neighbours in the hot times, and always listen to advice from your local emergency services.

You can visit the Bureau of Meteorology website to view the latest outlook, or subscribe to receive climate outlooks via email.

Catherine Ganter, Senior Climatologist, Australian Bureau of Meteorology and Andrew B. Watkins, Head of Long-range Forecasts, Australian Bureau of Meteorology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.