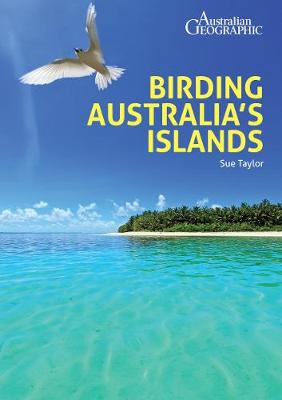

‘The birder must be self-sufficient’: how to bird Australia’s islands

Australian Geographic readers can receive a 20 per cent discount on Birding Australia’s Islands if they call (02) 8445 2300 and quote promo code ‘bird’ or if they order securely online at https://woodslane.com.au/promotion/bird and quote the promo code at the checkout.

OVER MY MANY years of birding I’ve visited lots of islands and I write about 22 of them in my new book Birding Australia’s Islands.

Each island is different in its own special way.

Some islands are easily accessed, like driving over the bridge at San Remo to get onto Phillip Island to see little penguins.

Others are more difficult to access, such as Macquarie Island, which takes five usually extremely rough days in the Southern Ocean. Birders go to Macquarie for the shag, penguins, albatross and the exotic redpoll.

Sometimes special permits are required, such as the islands in the Torres Strait and Ashmore Reef.

Some birds are easy to see – you can’t miss Christmas Imperial-Pigeons on Christmas Island.

Some birds are hard to see – Norfolk Parakeets were always difficult and I believe they are becoming rarer and harder to see.

Sometimes I’m lucky, as with the chinstrap penguin on Macquarie; more often I’m not, as with Saunders’ tern on my first visit to Cocos.

Before a birder visits any new location, be it on an island or the mainland, a fair bit of time will be spent studying all the birds likely to be encountered – what they look like, what they sound like, their habits and their habitats.

Planning and forethought is always required before any birding trip. More planning is required if the birder is travelling somewhere remote.

Then the birder must be self-sufficient. You can’t pop down to the local pharmacy for a bandaid to put on that unexpected blister if you’re on Ashmore Reef.

Today, the islands requiring the most preparation are those in the Torres Strait. It was not so on my first visit to Boigu in January 2006.

A group of us was birding in Bamega on the tippy-top of Cape York and hired a small plane to fly to Boigu. We undertook no preparation; simply hopped onto the plane.

When we landed our leader made himself known to the local chief and we were free to bird as we pleased. It had been hot in Bamega, but it was unbearably, oppressively searing hot on Boigu. I added Collared Imperial-Pigeon to my list and couldn’t get back onto the plane quickly enough.

Some years ago I did a birding trip in the Kimberley. On our first day our leader handed each of us a box of matches with the instruction that if we became lost, we should set fire to the bush so we could be located.

Believe it or not, this is true.

We all looked at each other and silently vowed that the last thing we’d do would be to start a bush fire intentionally. I think now that our leader was not expecting us to burn the countryside, but (giving him the benefit of the doubt) he was attempting to impress upon us that we were in very remote country and we should stay alert at all times. He certainly succeeded in focusing our minds.

It was the same with preparations on my subsequent trips to the Torres Strait. We did not simply hop onto a plane on these occasions.

First, we were instructed that we must purchase gaiters because of the lethal snakes. Particularly aggressive and deadly Papuan taipans and Papuan black snakes were mentioned, with accompanying terrifying tales of recent unfortunate victims. The gaiters were uncomfortable and difficult to walk in, but we all persevered staunchly.

Then there were the diseases. I remember malaria and Japanese encephalitis. I took anti-malarial medication, notwithstanding the fact that one of the potential side effects (which, fortunately, I did not suffer) was diarrhoea.

Can you imagine suffering from diarrhoea while confined to a small boat with twelve other people?

I also soaked all my clothes in permethrin and, while this took time that I’d rather have spent studying birds, it proved to be time well spent. I had an injection for encephalitis, although my doctor was most reluctant to administer it because she said the side effects were worse than the risk of the disease. Again, luckily, I had no side effects.

Just like the matches given to us by our tour leader in the Kimberley, whether or not snakes and diseases were a likely threat, discussion of these things before we left home certainly focussed the mind.

We flew to Cairns, then to Horn Island, where we boarded the boat that was to be home for the next week.

I saw some good birds in the Torres Strait. I knew I’d see Red-capped Flowerpeckers and Singing Starlings. I’d secretly hoped to see Gurney’s Eagle, but I was surprised and delighted to add Zoe’s Imperial Pigeon and Coronated Fruit Dove to my list. However, I dipped on Coconut Lorikeet, a common bird, so I had to go back again.

On my third trip to Torres Strait I did eventually see a pair of lorikeets flash overhead, but I cursed when I realized they were not common Coconut Lorikeets but their much rarer Red-flanked cousins.

Happily, I can report that I did finally see my Coconut Lorikeets, just by happenstance. Cyclone Nora forced us to shelter between islands and here the lorikeets flew overhead.

Initially, I’d been upset that the cyclone had changed our route – we had planned to visit another island and who knows what birdy treasures lay await for us there? But, thank goodness we were forced to shelter and I could eventually add Coconut Lorikeet to my list.

I reckon three trips to the Torres Strait to see what is supposed to be a common bird is quite enough.

It is disappointing to prepare well, travel a long way, and miss out on seeing your quarry. But then it does provide an excuse to return, which is always welcome.