The darker side of Antarctic heroism: the story of Sidney Jeffryes

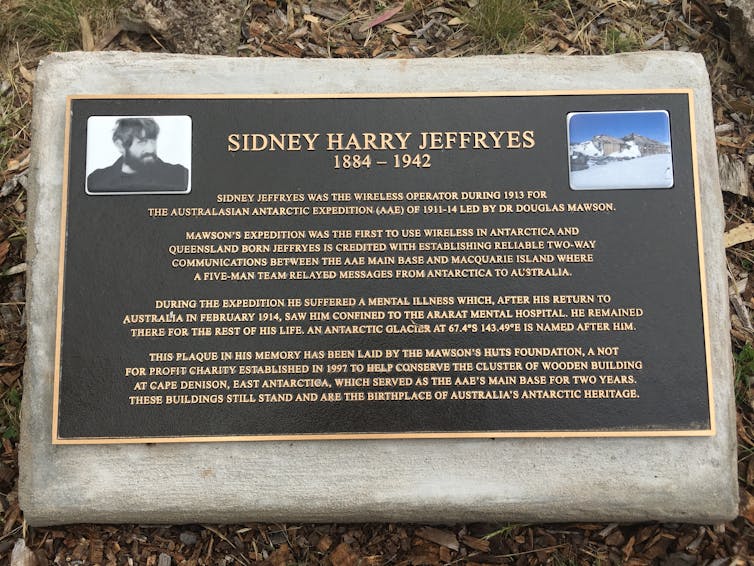

AN UNMARKED grave in the public cemetery at Ararat has been the resting place of Sidney Jeffryes, the remarkable radio operator of Douglas Mawson’s Australasian Antarctic Expedition.

In 1913, Jeffryes achieved a world first when he made ongoing two-way wireless contact between Antarctica and Australia. However, his mental illness during the expedition, and his subsequent committal to a high-security asylum, meant his contribution was swept under the carpet.

Only now has his important role in Australian Antarctic history been recognised with the laying of a plaque on his grave.

A Queenslander, Jeffryes was working as a shipboard radio operator and already making claims to long-distance telegraphy records when in 1911 he applied for a position on Mawson’s expedition. Although another applicant was selected, Mawson considered Jeffryes a “very good man”.

It is unsurprising, then, that the following year, when the expedition vessel, the Aurora, left Hobart to bring the expeditioners back from Antarctica, Jeffryes was offered a place as its wireless operator. What he didn’t realise was that he would end up spending an unexpected year in the far south.

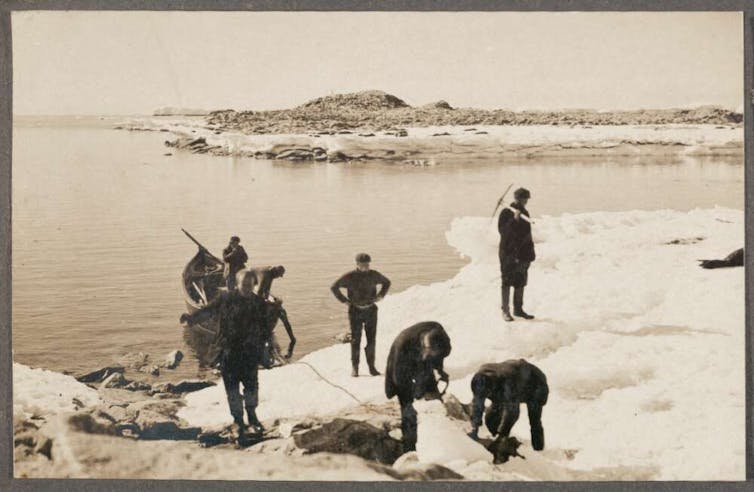

When the Aurora arrived at the expedition hut in Commonwealth Bay to take all the men home, three were missing: a sledging party led by Mawson had failed to return. With the season growing late, the ship’s captain had to leave to collect a group of men at another continental base. So he took most of the expeditioners with him, leaving five behind to wait for the missing party. Jeffryes agreed to stay behind and take the place of the original radio operator, Walter Hannam.

When Mawson returned to the hut, he was alone. His two companions had perished during the journey. Thus began a very trying year. Mawson was recovering from an extremely arduous journey, and he and the five men from the original expedition were mourning the loss of two beloved friends. As the only newcomer to the hut, unused to the extreme conditions, and under pressure to make the wireless work better than it had, Jeffryes was in a difficult position.

Despite these pressures, he made a success of his unanticipated role. In March 1913 the Australian press celebrated the establishment of wireless contact with Australia. The expeditioners were delighted to be able to communicate with their loved ones, although there was tension over whose messages would get priority. Jeffryes had to operate under testing circumstances, working late into the night, when reception was best, to try to pick up the faint and noisy messages.

In June 1913, after a particularly strong gale, the always troublesome wireless mast blew down, making it impossible to send or receive messages. Shortly afterwards, Jeffryes began exhibiting unusual behaviour, at one point challenging another man to a fight.

‘Delusional insanity’

Over the next few weeks he exhibited a series of symptoms – including delusions of persecution, paranoia and decline in hygiene – that are consistent with what we now classify as schizophrenia. The expedition doctor, Archie McLean, diagnosed “delusional insanity”. With none of the men able to leave the hut in the freezing, dark winter, the situation became very trying for all.

Believing his companions were trying to murder him, Jeffryes began sending out messages secretly on the wireless, including one saying that five others were “unwell” and he and Mawson would have to escape. Luckily, it was never received, but Mawson eventually dismissed Jeffryes – a strange situation given he was unable to leave his workplace.

The seven men struggled through the next few months, and were relieved when the Aurora arrived to pick them up towards the end of 1913. Jeffryes’ behaviour remained erratic and he took no part in the celebrations that greeted the expedition on its arrival in Adelaide in February 1914.

Nonetheless, he was allowed to board a train alone, presumably headed home to distant Toowoomba. The next that was heard of him was media reports that he had been found wandering in the bush in regional Victoria, starving despite the money in his pocket, and saying Mawson had hypnotised him.

Jeffryes was quickly committed to Ararat Hospital for the Insane (as it was then called). Initially his prognosis was hopeful, and he was transferred to Royal Park and Sunbury asylums in the hope a change of scenery would help. In Sunbury, however, he attacked a staff member, which landed him back in Ararat, this time in “J-Ward”, the facility for the criminally insane.

Life in the high-security ward was notoriously hard and the temperatures could be very low; a cell in J-Ward must have made the hut in Antarctica look like a picnic. Yet Jeffryes survived for another 28 years, until his death from a cerebral haemorrhage in 1942.

With mental illness highly stigmatized in the early 20th century, and incongruous with the heroic framework within which Antarctic explorers were viewed, Jeffryes’ part in the expedition was deliberately downplayed. He gradually vanished from exploration history, his impressive achievement largely forgotten.

This changed today (Tuesday), when Mawson’s Huts Foundation chairman David Jensen unveiled a plaque on Jeffyres’ grave, officially marking his contribution to wireless history and Australian Antarctic history.

We are moving beyond our obsession with heroes and now telling richer, more complex accounts of human presence in the far south.

This article was co-authored by Ben Maddison.![]()

Elizabeth Leane is an Associate Professor of English and ARC Future Fellow at the University of Tasmania and Kimberley Norris is a Senior Lecturer in Psychology at the University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.