Australia’s 10 deserts

Australia is the driest inhabited continent in the world – only Antarctica is drier. Seventy per cent of the mainland receives less than 500mm of rain annually, which classifies most of Australia as arid or semi-arid. While the Simpson and the Great Victoria deserts are the best known, Australia has a total of 10 deserts.

Defining a desert in Australia is complicated. Typically defined as areas receiving on average less than 250mm of rain per year, Australia’s deserts can sometimes technically exceed this average due to our uneven rainfall distribution. Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology therefore uses three formulas to define our deserts, which make up a whopping 18 per cent of Australia’s entire landmass.

Listed from greatest size to smallest, these are Australia’s ten deserts:

- Great Victoria Desert (348,750sq.km)

- Great Sandy Desert (267,250sq.km)

- Tanami Desert (184,500sq.km)

- Simpson Desert (176,500sq.km)

- Gibson Desert (156,000sq.km)

- Little Sandy Desert (111,500sq.km)

- Strzelecki Desert (80,250sq.km)

- Sturt Stony Desert (29,750sq.km)

- Tirari Desert (15,250sq.km)

- Pedirka Desert (1250sq. km)

Perfect desert conditions

Australia’s positioning has created prime conditions for an abundance of deserts as multiple factors converge to create arid climates. In the subtropics, a belt of high pressure exists globally at about latitude 30 degrees north and south – the latter runs across Western Australia and South Australia and through the Great Victoria Desert. That pressure creates dry conditions that are carried by a general easterly flow that spreads the arid landscape through the Northern Territory and northern Western Australia. Then, locked away from the coast, these desert areas are separated from moisture sources.

In summer temperatures soar throughout Australia’s deserts, although not to the extremities we might imagine. On average, days reach above 35°C but hot spells of above 40°C can stretch out over weeks. At night, temperatures can stagnate and remain around 30°C, though they tend to drop within a 15-20°C range. The Pilbara region in Western Australia is the hottest area of the desert, known to reach 48-50°C. But, compared to Iran’s deserts – such as the Dasht-e Kavir (Great Salt Desert) where 50°C days are common throughout summer, or the Lut desert, home to the world’s hottest recorded temperature of 70.7°C in 2005 – Australia’s deserts pale in comparison.

In winter, daytime temperatures drop to averages of below 15°C in the south and 25-27°C at the arid zone’s northern boundaries. In July, average night-time temperatures sit between 3-6°C. Higher elevated areas, such as Alice Springs, have seen night temperatures as low as -7.5°C, slightly colder than an average winter’s day in St Petersburg. However, when compared to the Gobi Desert, Australia’s plains are toasty – overnight temperatures there can drop to -40°C.

Rainfall, or lack there of

Australian deserts average an annual rainfall below 250mm. The rainfall is rarely evenly spread throughout the year – often the annual average will fall in a month, and has been known to fall in a single day.

Compared to the eastern Sahara however, which has an average rainfall below 10mm, Australia’s deserts are abundant with water. Australia’s one recorded instance of a complete rainless calendar year was in 1924 at a station in Mulyie, about 100km east of Port Hedland in Western Australia. But the world’s driest desert, the Atacama, which spreads across Chile and Peru, has sections that have not seen rain for hundreds of years.

Desert communities

Because of its harsh conditions, few call Australia’s deserts home. Less than 3 per cent of the population, or less than 600,000 people, live in the desert region. Yet Indigenous Australians have inhabited the land for tens of thousands of years, some communities continuing to do so. Aboriginal communities including but not limited to The Spinifex People of the Great Victorian Desert, the Martu people of Australia’s Pilarba deserts, and the community of Yuendumu on the edge of the Tanami desert continue to live within or on the surrounds of these dry plains.

Lake Eyre

The most arid and dry parts of Australia centre around the Lake Eyre basin, which can range from an average rainfall of 100mm to 140mm per year. Lake Eyre, also known as Kati Thanda, is the fourth largest terminal lake in the world and Australia’s lowest point at 15.2m below sea level.

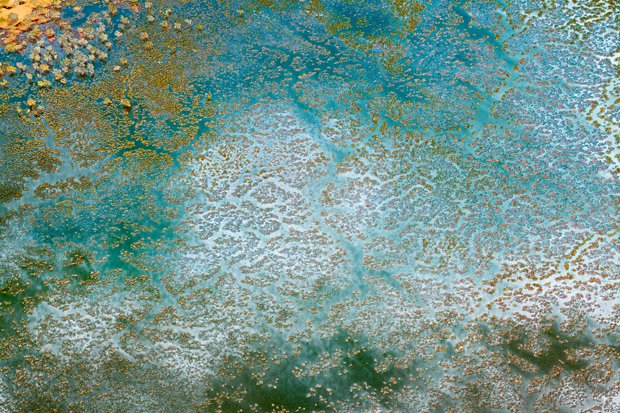

The lake is an inward draining catchment spanning 1.2 million sq.km, yet it is rarely filled with water. Because of natural aversion in the landscape, most water is lost as it travels towards the lake through evaporation and infiltration. As the lake evaporates, only salt from the water remains – Lake Eyre is usually a salt flat, a white and barren landscape.

When the lake does flood in rare heavy rains, the landscape is transformed. A kaleidoscope of colour blooms with wildflowers and wetland foliage, while waterbirds flock and endemic frogs and fish quickly appear.

Temperamental climate

According to Dr James Cleverly, Research Fellow at the School of Life Sciences at the University of Technology, Sydney, Australia’s deserts are exceptional not for extremities, but their constantly fluctuating climates.

“The big thing that distinguishes the deserts of the Indian Ocean rim nations (Australia, India, Somalia) is the very large fluctuations in climate that can be experienced over very few – for example, the drought and bushfires of 2009 followed by the floods and transformation of the land to a green paradise in 2010–2011,” he says.

“Even these prominent events are small compared to the extremes in drought and flooding rains over the last one hundred years – rainfall inferred from the historical record at the Territory Grape Farm, NT, reported a low of 25mm in 1928 and a high of 955mm in 1974.”

What is most impressive is that Australia’s endemic flora and fauna are resilient to not only these harsh conditions, but their dramatic shifts.

Desert flora and fauna

Rich and diverse communities of endemic plants and animals have adapted to exist in Australia’s arid areas.

“The desert is filled with woodland, grassland, and savanna plants,” says James. “Amongst these desert plants, mulga covers 20–25 per cent of the continental land area, and spinifex covers another 20–25 per cent of the land.”

Australia’s deserts are home to a variety of endemic animals too, including reptiles, birds, mammals, frogs, and insects. Because of the sheer size of our arid regions, knowledge of the deserts fauna continually shifts as new species are discovered.

Of all deserts worldwide, Australia’s have the richest diversity of lizard fauna. Over 210 species of reptiles live throughout arid Australia – the most infamous is perhaps the desert death adder snake (Acanthophis pyrrhus). Despite its name, the death adder’s venom is, according to the Clinical Toxicology Resources at the University of Adelaide, slightly less potent than the venom of the common brown snake, the tiger snake, or the taipan. Yet in the desert, away from medical attention, a snake’s bite is much more difficult to treat.