Back in 2015, a brilliant young musician named Valda Wilson was a principal operatic soprano with the Oldenburg State Theatre in Germany. This rising Australian star was well on the way to realising her artistic ambitions on the major stages of Europe. A long way from home, Valda wrote an impassioned letter to a Sydney local council, so concerned was she as to the fate of one of the city’s small, and most unusual, cultural gems.

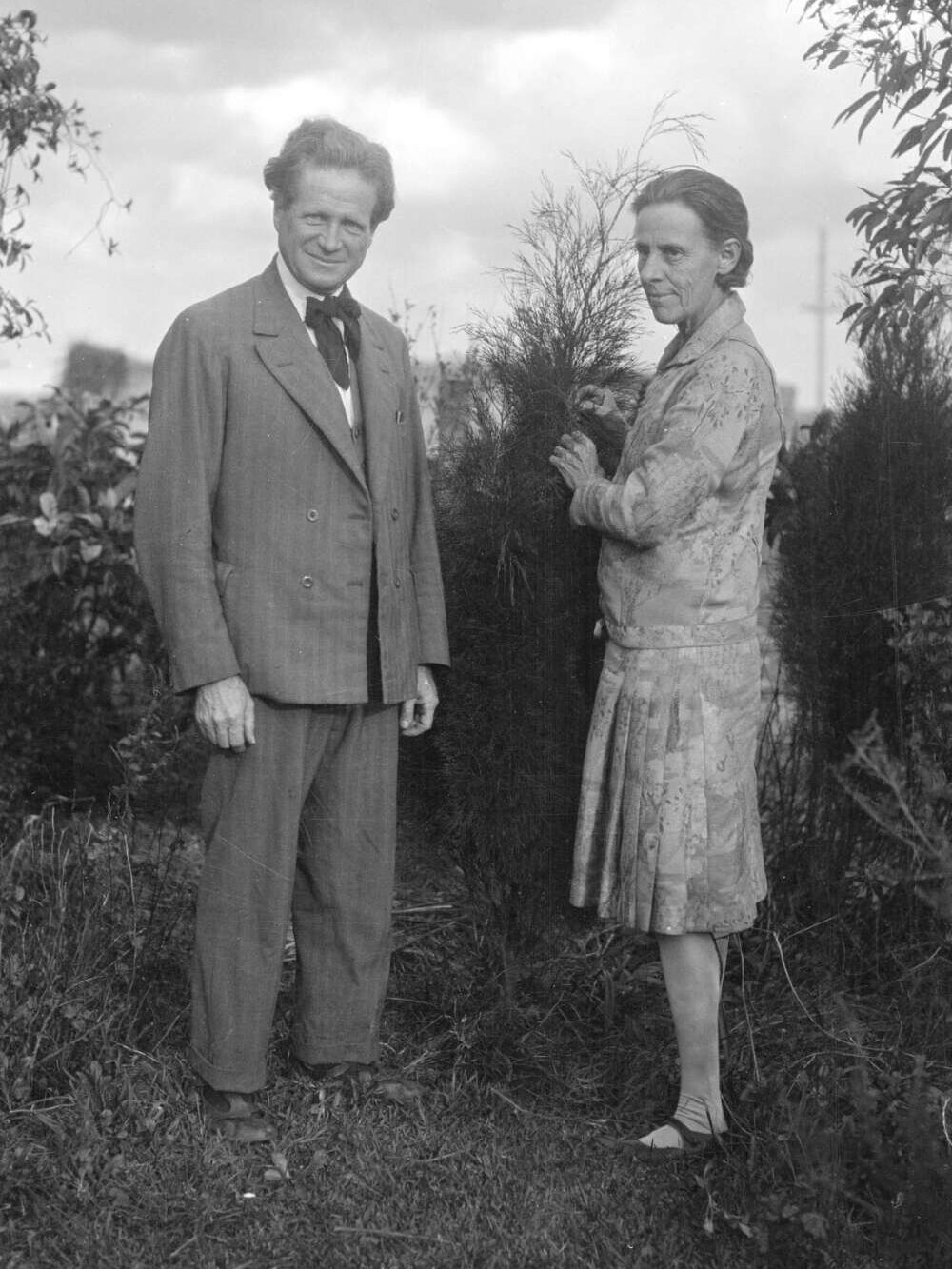

Valda grew up in Castlecrag, a suburb in the Willoughby local government area in Sydney’s lower north shore. The harbourside enclave had – and still has – bush-swathed blocks and narrow sinuous roadways that, rather than fighting against the topography, yielded to its contours. Castlecrag is a suburb unlike any other in Australia. The land had been subdivided and partly built upon back in the 1920s and ’30s by that extraordinary American husband-and-wife architectural and landscape design duo, Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin. After winning an international competition to design a capital city for the newly federated Australia, the Griffins arrived in Australia from Chicago in 1914, just months before the outbreak of World War I. The Canberra project soon became mired in acrimony and political chicanery … but that is another story.

While the Griffins’ early years in Australia were spent in Melbourne, the temporary seat of the nation’s capital, the bush-clad hillsides and jewel-like waterways of Sydney held a magnetic attraction. In 1921, they purchased an initial 263ha tract of land on Middle Harbour that they planned to turn into a model suburb, all the while adhering to the principal of designing and building with nature and not against her. The Griffins named their estate Castlecrag and moved back to Sydney in the mid-1920s. The adjoining Haven Estate was added in 1926. Because of their appreciation for nature and the rugged topography that made parts of the land impractical to build upon, their subdivision would be endowed with a precious network of reserves. These were to be set aside for both nature preservation and community enjoyment.

So, what prompted Valda Wilson to contact the councillors of Willoughby City while busily forging her career on the other side of the world? Her concerns centred on one of the Griffins’ small bushland reserves where some of her most precious and formative memories of growing up in Castlecrag were created.

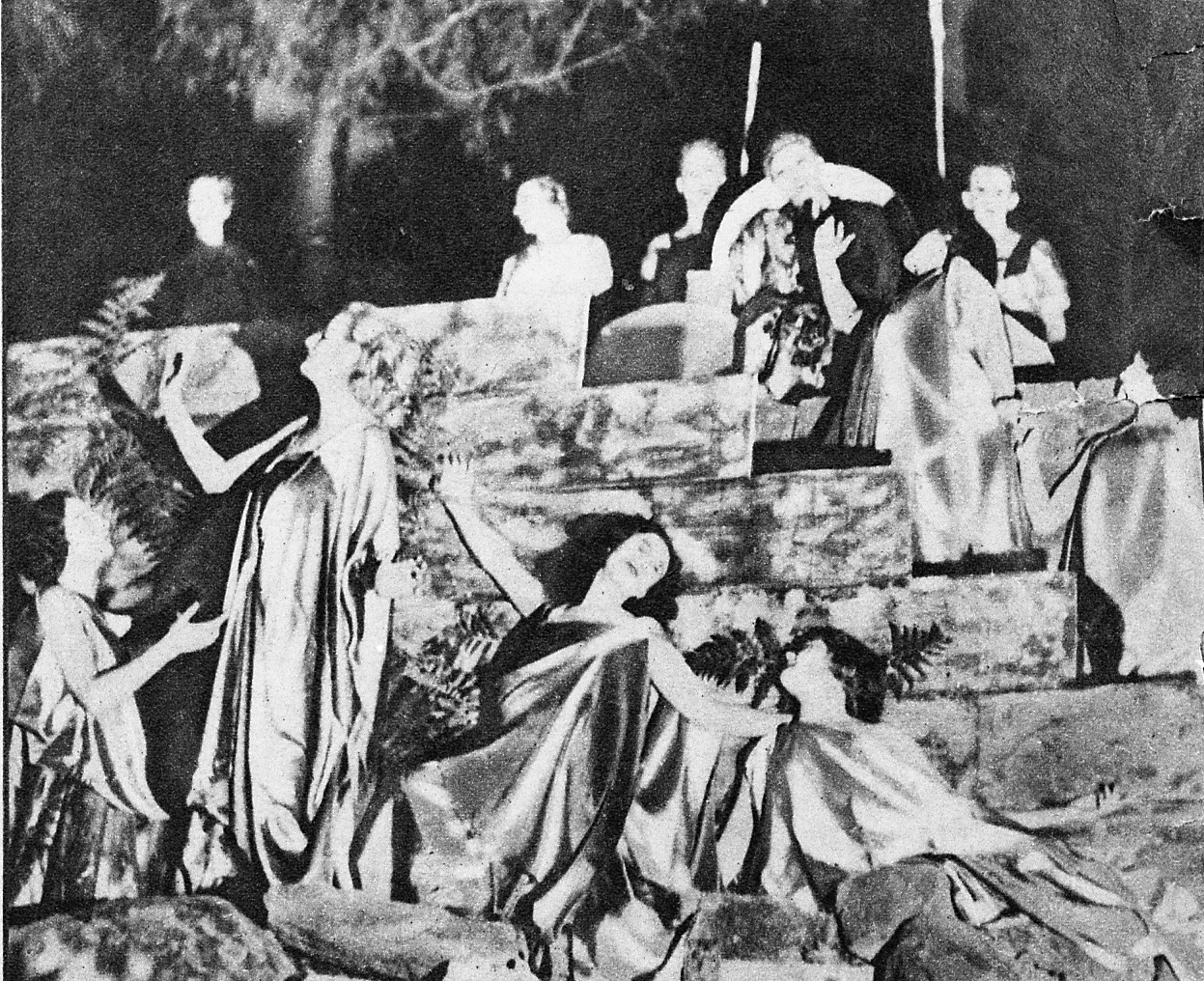

But the area that so occupied her thoughts was much more than a leftover remnant of bush flanked by roads and houses. Within the Haven Estate is a forested reserve that stretches down to the harbour. And there in that beautiful little valley, replete with a small creek and embraced by stately angophoras and delicately fronded tree ferns, is an open-air theatre that the Griffins created in the early 1930s. Known initially as the Haven Scenic Theatre, and later the Haven Amphitheatre, this extraordinary space became a focus of much activity in the small but vibrant theatre scene in Sydney during the Great Depression. Marion was the Haven’s intellectual driving force, with Walter providing the creative input in modifying the gully’s terrain to create terraced stone seating and, on occasion, making elaborate theatre sets.

The theatre was built almost entirely by volunteers from the fledgling Castlecrag community. There was no stage as such, but the Haven’s spectacular ensemble of natural rocky ledges and giant sandstone tors made for an organic drama that no indoor theatre could rival. Production lighting was often provided by car headlights, carbide lamps and kerosene lanterns.

Under Marion’s lead, the theatre flourished for a few brief years. Most of the performers were amateurs, but as historian Jill Rowe has remarked: “The plays produced at Castlecrag were not home entertainments, nor was the mode in any sense ‘little’. Rather, it … [became] a matter of grand and memorable productions of great plays, most remarkable at night and in the open air.”

Audiences of up to 150 would brave the hard seats and the unwanted attentions of mosquitos, with some of the memorable offerings including Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, scenes from Goethe’s Faust, and the Ancient Greek dramas Electra and Antigone.

In 1935, Walter travelled to Lucknow in northern India to work on an architectural commission for a university library. Extra work poured in, so Marion joined him there in 1936. But in early 1937 the unthinkable happened: Walter died. A devastated Marion came back briefly to Australia before returning to Chicago for good in 1938. With the Griffins gone, interest in the Haven dwindled.

By World War II, the lights had literally and metaphorically gone out and the gully was soon overgrown, choked by weeds and reduced to a dumping ground for household refuse. Much of the stone from the terraces somehow found its way into surrounding gardens, and the Haven lay in a forgotten and sorry state until the 1970s when local bush regeneration volunteers cleared the rubbish and rediscovered what remained of the seating. Local volunteers worked beside a building contractor to bring the Haven back to life. Castlecrag architect Robert Sheldon designed a timber stage and his wife Patricia became the initial successor to Marion as the Haven’s artistic maestro. In 1969, a visionary cameraman and film and television director named Howard Rubie took up residence on the Castlecrag waterfront. With relentless energy, Howard restored much of the Haven’s magic until his death in 2011.

The first production at the reborn theatre was Oscar Wilde’s Salome. To honour the Griffins, the production coincided with celebrations of the American bicentenary in 1976. Howard cajoled his professional colleagues to fill the major roles and provide backstage expertise. Volunteers did the rest. And so began a production pattern that endured until the Haven’s second sad demise in 2016.

Some sections of the timber structure had begun to rot in the 1980s so the stage was partly rebuilt and extended in several phases between 1991 and ’93. A greenroom and toilet facilities were added as an undercroft. The improved stage ushered in the Haven’s glory years; throughout the 90s and 2000s, hundreds of shows were presented across a range of genres. Opera stars and jazz musicians, Shakespearean actors, cabaret artists, dance troupes and acrobats – they all trod the boards at the Haven and made the little valley ring with their glorious sounds. And all this was under an arc of stars, sun or the glow of a full moon and a close canopy of tree ferns painted with enchanting light. The likes of jazz greats James Morrison and Graeme Jesse, renowned composer Nigel Westlake, opera diva Elizabeth Connell and Canadian queen of cabaret Patricia O’Callaghan all thrilled eager audiences oblivious to the lack of a cushy seat or air-conditioned comfort.

And, of course, the Haven was where Valda, that little girl turned international soprano, got her start. In her letter to the Willoughby City Council, Valda wrote: “For most young people, a theatre visit means buying tickets and waiting to be entertained. But not for those of us who knew about the Haven. Here we were welcomed by an enthusiastic team of volunteers, many of whom had professional lives as musicians [and] actors. As children we were encouraged to … learn about all the tricks of the trade by working alongside these talented people.”

Valda’s letter was a plea to the council to allow the Haven to “continue to nurture and encourage the creativity of young people and be a focal point of community involvement and celebration”. But, at the time, the Haven was in peril.

The old stage was again somewhat the worse for wear, and the council declared it structurally unsound and non-compliant with current building standards. A proposal to replace the timber stage with concrete was opposed by a vocal faction, who declared the material anathema to the spirit of the Griffins.

Acrimonious debate shattered the tranquility of Castlecrag. As the arguments to repair or replace the stage reverberated across the Haven gully, remedial works were deemed impractical by the council and a wasteful use of its funds. Pending a development application for a replacement, the council had no option but to send in a demolition crew. Plans were drawn for a new stage on a steel frame, plus disabled access to the site, but the design won few accolades among the community and the approval lapsed in 2023.

The occasional small-scale or council-funded performance still occurs in the Haven gully, which is now back to much the way it looked in the 1930s. But the enchanted nights of those glory years are long gone, perhaps never to return – a tragedy for the Castlecrag community and the cultural life of Sydney and beyond.

Back home for a visit in 2015, Valda told one of her Haven colleagues the calming “mind exercise” she did before singing in front of 2000 people with the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House at the thanksgiving service in Westminster Abbey for Dame Joan Sutherland. She looked out at the invited luminaries in that vast space, with its towering, vaulted ceiling, and thought: “There are the candles at the Haven. It’s all good. Just chill. There’s the little creek and the trees overhead. You’re safe.”

She laughed, then added, “And then I sang quite well!” Such was the magic of the Haven.