Defining Moments in Australian History: The Black Death

Bubonic plague, or the ‘Black Death’ as it became known during the pandemic of the 17th century, is one of the most deadly diseases to which humans have ever been exposed.

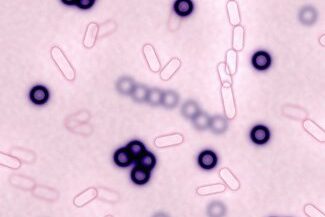

The disease is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which infects the oriental rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis), which in turn infects a host, usually the black rat (Rattus rattus).

Black rats often live close to humans and feed on stored produce such as grain. The fleas move from rats to humans who become infected by Y. pestis when the fleas bite.

The bacteria move quickly from the bite site into the lymphatic system, causing acute inflammation of the lymph nodes. As the nodes break down, toxins spread through the body causing massive haemorrhaging in internal organs, discolouring the skin – hence the name Black Death.

The three worst bubonic plague pandemics are among the greatest natural disasters of all time. In 541AD the plague arrived in Constantinople (now Istanbul) – then the world’s largest city – possibly carried north from the Sudan up the Nile aboard grain ships, and then across the Mediterranean Sea.

During the following year, the plague killed 40 per cent of Constantinople’s population and eventually a quarter of the population of the eastern Mediterranean. It spread across Europe, reaching England by 664. Frequent smaller outbreaks occurred across Europe until 750 when the disease disappeared.

In 1348, however, plague erupted again in Europe, when Genoese soldiers returning from the Crimea unknowingly transported Y. pestis back to Italy.

The plague spread rapidly across the continent and was most virulent between 1348 and 1356. The pandemic became the deadliest event in human history, killing a quarter of Europe’s population. It contributed to the end of the feudal system in Europe because there were no longer enough peasants to work the estates. Civic administration separated from the Church, and scientific inquiry was stimulated in an attempt to understand the disease.

The third pandemic began in China in 1855. By 1894 it had reached Hong Kong, with 100,000 deaths reported that year. In 1896 it spread to India and in 1899 Nouméa in New Caledonia was declared a plague-infected port.

Australian authorities were acutely aware that it was only a matter of time before the disease reached the continent. The first case was that of Arthur Paine, diagnosed on 19 January 1900. He was a delivery man at Sydney’s Central Wharf where ships carrying infected rats would have docked. By the end of February, 30 cases had been reported and there were concerns the colony was on the brink of an epidemic.

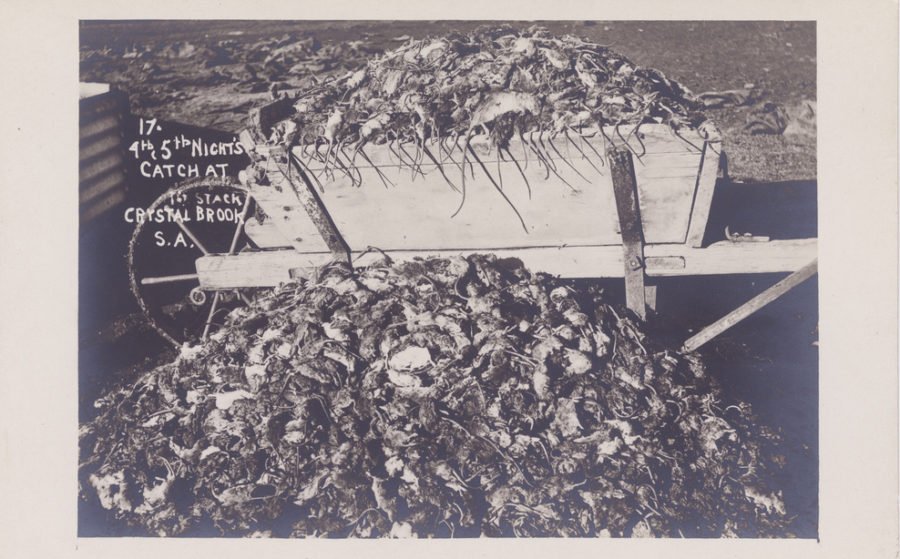

Authorities instituted a threepronged response: the quarantining of infected individuals at Sydney’s North Head; intensive cleaning and demolition of parts of Sydney’s inner city; and a rat extermination program.

In the first nine months of 1900, 1759 people were quarantined, of whom only 263 were confirmed as cases of plague. Lime, carbolic water and lime chloride were used to disinfect dwellings, and all waste matter was burnt. The government paid two pence per rat delivered to an incinerator on Bathurst Street. More than 108,000 rats were killed by government employees.

The plague continued to reappear annually in Sydney until 1910, with cases also popping up in Queensland, Melbourne, Adelaide and Fremantle. In total, 1371 cases were reported with 535 deaths across the nation. Australia’s coordinated response to the plague outbreak was instrumental in proving the importance of public health and modern, sanitary urbanplanning principles in controlling the spread of infectious diseases.

‘The Black Death’ forms part of the National Museum of Australia’s Defining Moments in Australian History project.