Looking back at Australia’s largest political demonstration

The 2000 Walk for Reconciliation across the Sydney Harbour Bridge was a landmark event that sparked similar actions around the nation during the weeks that followed. But it grew out of actions that ocurred almost a decade earlier in 1991, when the Federal Parliament created the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation, which promoted this vision for “A united Australia which respects this land of ours; values the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage; and provides justice and equity for all.”

Creation of the council came in response to the findings of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, which highlighted an urgent need for “a formal process of reconciliation between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous peoples”.

A series of critical events relating to Indigenous rights, respect and recognition followed throughout the 1990s. In 1992 one of the most momentous was the handing down by the High Court of Australia of the Mabo decision, which ruled that, when Britain made its claim to this continent in 1770, Australia was not terra nullius – a land belonging to nobody. Indigenous peoples, the decision acknowledged, had lived in Australia for thousands of years and had rights to the land under their own laws and customs.

Within 12 months the Native Title Act 1993 was passed, paving the way for First Nations people to claim legal ownership of traditional lands. The Wik decision followed in 1996, confirming that native title rights and pastoral and leasehold tenures could coexist and, perhaps even more significantly, that native title could not be extinguished by pastoral leases.

At about the same time, in 1995, Australia’s Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, under the request of the federal government, conducted The National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families. The inquiry tabled its findings in Federal Parliament in 1997, in the landmark Bringing Them Home report, which addressed the institutionalised forced removal of First Nations children from their families throughout the 20th century, right up to the 1970s.

It was the first time this disturbing part of modern Australian history had been documented in a formal way, and the extent and nature of the practices it highlighted shocked many non-indigenous Australians.

The report made 54 recommendations aimed at redressing the impacts of the removal polices and the ongoing intergenerational trauma they’d caused. Among the recommendations was a national apology.

A year after the Bringing Them Home report was tabled, the first National Sorry Day was held on 26 May 1998, recalling the Stolen Generations as one of the most tragic and deeply emotional events in recent Australian history. It’s a day that’s been marked annually ever since, acknowledging the deep trauma suffered by generations of First Nations people who were forcibly removed from their families and communities under the sanction of misguided government-endorsed policies.

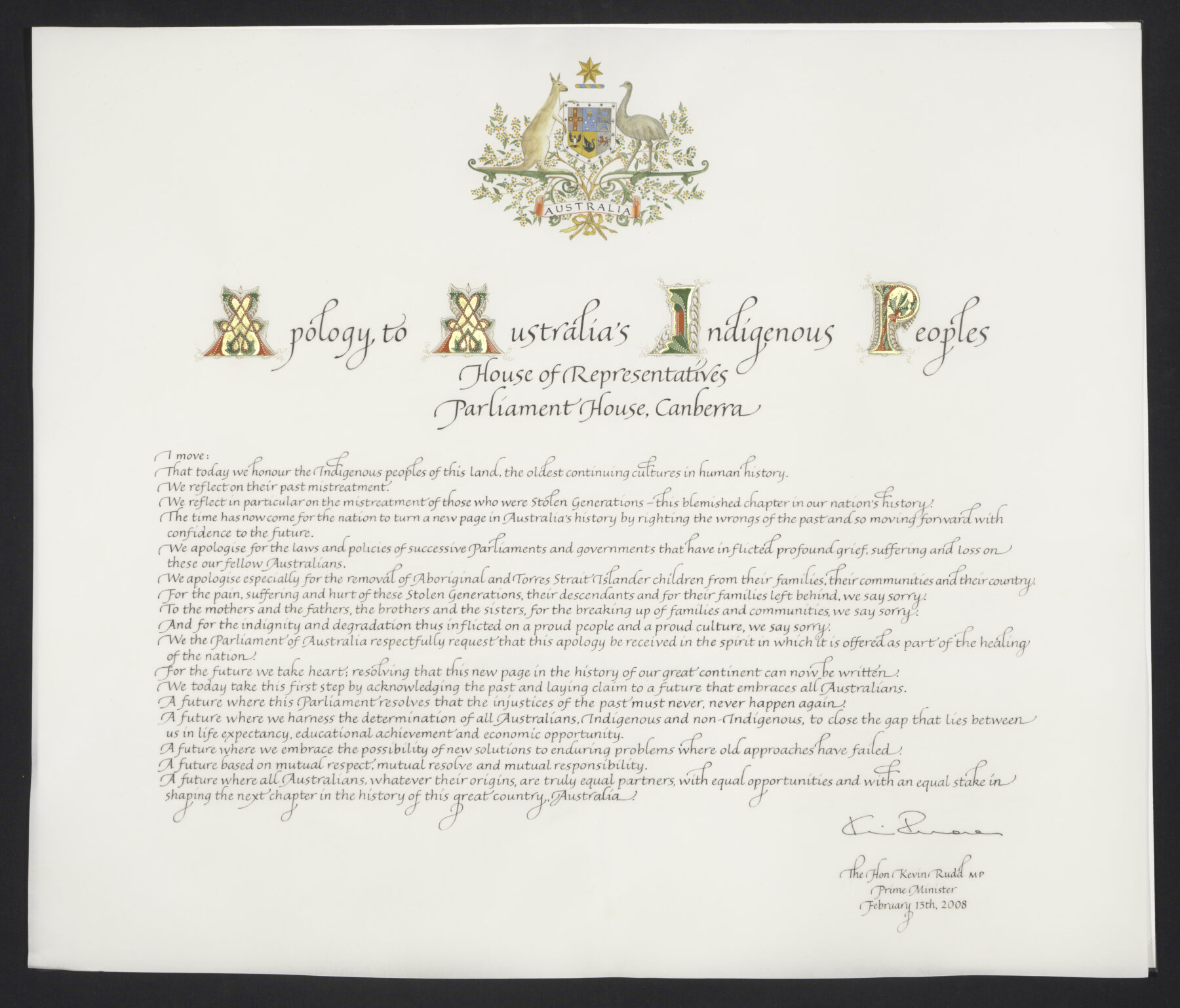

The Walk for Reconciliation came two years after the first Sorry Day, while the National Apology to Australia’s Indigenous peoples was formally offered in Federal Parliament on 13 February 2008, by prime minister Kevin Rudd, on behalf of the nation.