As a young child, Jim Ryan came across a treasure trove of items in the attic of his family’s home in New Bedford, Massachusetts, that told the story of one of the boldest prison escapes in Australia.

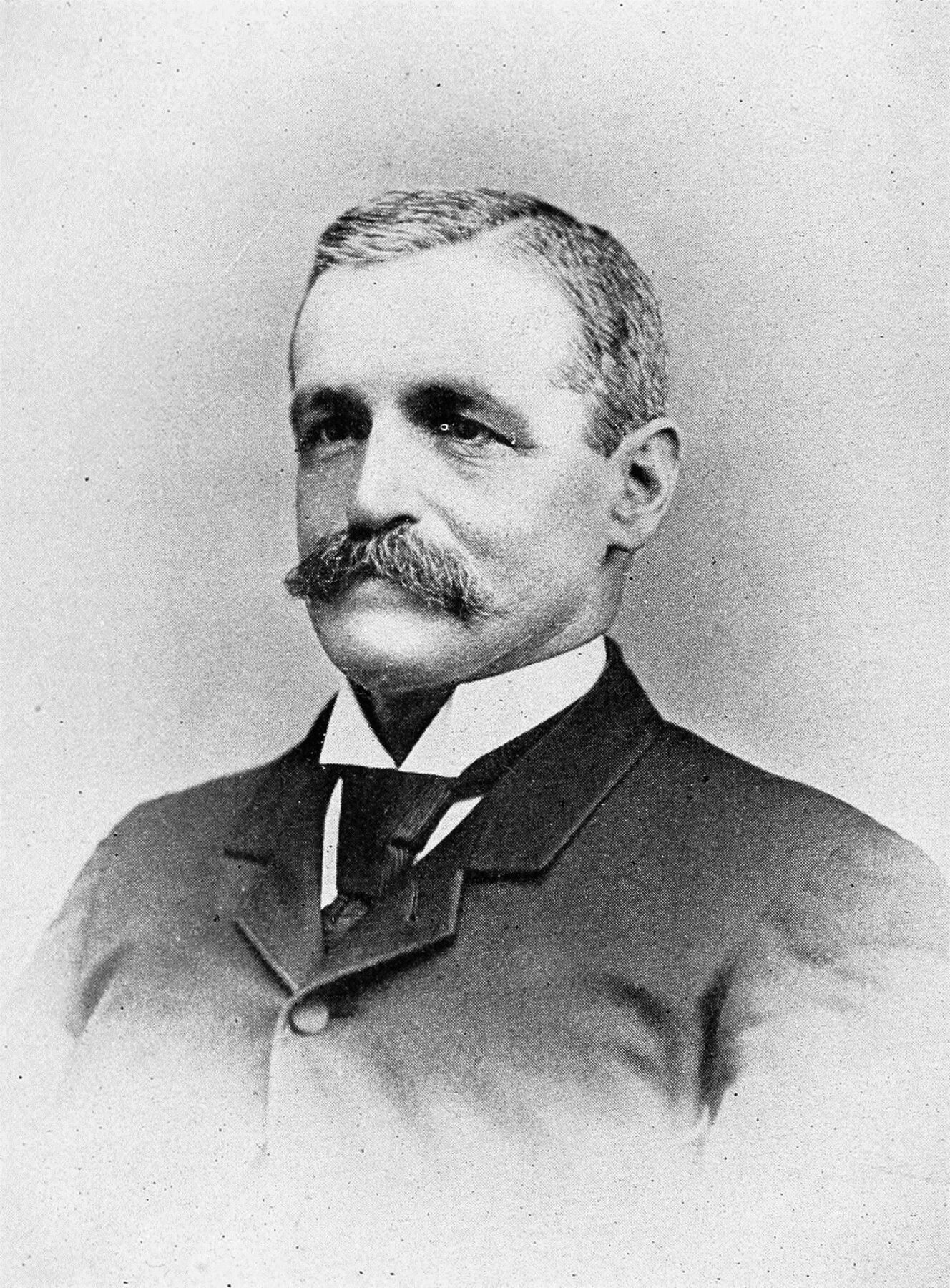

The collection of keepsakes stored for decades dates back to the 1870s when his great-grandfather George Anthony captained a whaling boat from the US to Australia and back again to smuggle six Irish political prisoners to freedom.

Anthony died in 1913 before his great-grandson was born, but Ryan’s interest in his forefather’s epic mission continued beyond a childhood curiosity, while in Australia the outlandish escape continues to be remembered.

An extreme escape

In 1875, Anthony was brought in on a secretive plan by his boat-fitter father-in-law who had been approached by men looking for a whaling boat and crew to retrieve a group of Irish prisoners from Australia.

Irish-Americans collected money from far and wide to finance efforts to free the men.

Ryan says people with Irish connections from across the country “gave nickels and dimes and pennies.”

“I don’t think everybody knew what was going to happen but everybody knew something was afoot,” he says.

The ‘Fremantle Six’

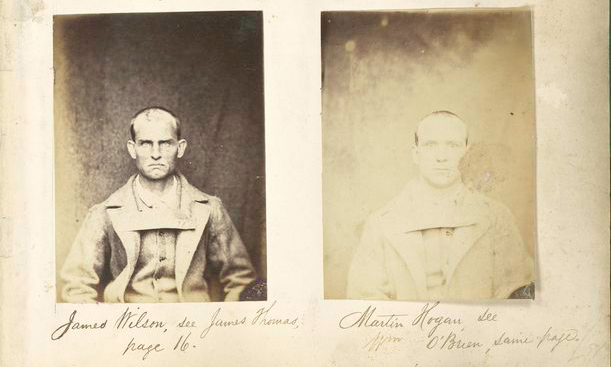

James Wilson, Thomas Darragh, Martin Hogan, Michael Harrington, Thomas Hassett, and Robert Cranston had been among Irish political prisoners sent to Australia as convicts.

Margo O’Byrne, a first-generation Irish-Australian, explains how the men had been imprisoned as a result of a political uprising in Ireland.

“The Irish had tried a number of times to get independence… finally they decided the only thing they could do was take up arms,” she says.

An unsuccessful uprising saw many Irish nationalists, referred to as Fenians, imprisoned.

In 1867, 62 Irishmen were put on a ship called the Hougoumont bound for Western Australia.

O’Byrne is a member of the Fremantle Fenians, named for those who arrived in the port city more than 150 years ago.

Along with the rest of the convicts, the Fenians were put to work building the British colony.

O’Byrne explains there was an amnesty movement to have the prisoners released “because it was actually illegal for Britain to send political prisoners to Australia.”

While most were freed, she explains, “those who previously served in the British Army, and then deserted in order to fight for Irish independence” were not.

Bound for Western Australia

As prisoners taken to Australia, they were detained in the Fremantle Prison and used to build public buildings, roads and bridges.

It was a letter smuggled out from Wilson, describing the years he’d spent in “a living tomb” that sparked the rescue plot.

The recipient of that letter spoke with others in the US Irish republican movement and a plan was hatched that eventually led to Anthony, Ryan’s great-grandfather.

While Anthony was not Irish, Ryan (who got his Irish name from his father’s parents who migrated from Ireland to the US) says he believed Anthony took on the task of sailing across the globe to give the Irish political prisoners their freedom as he thought it was the right thing to do.

Anthony had thought his days on the open ocean were over when initially approached.

He had worked on whaling ships from the age of 15, eventually becoming a first mate, before agreeing to his wife’s pleas not to go to sea anymore.

Ryan also reveals how Anthony, having tried several occupations since giving up whaling, had struggled to find something he enjoyed.

“I think he was looking forward to the challenge,” Ryan says.

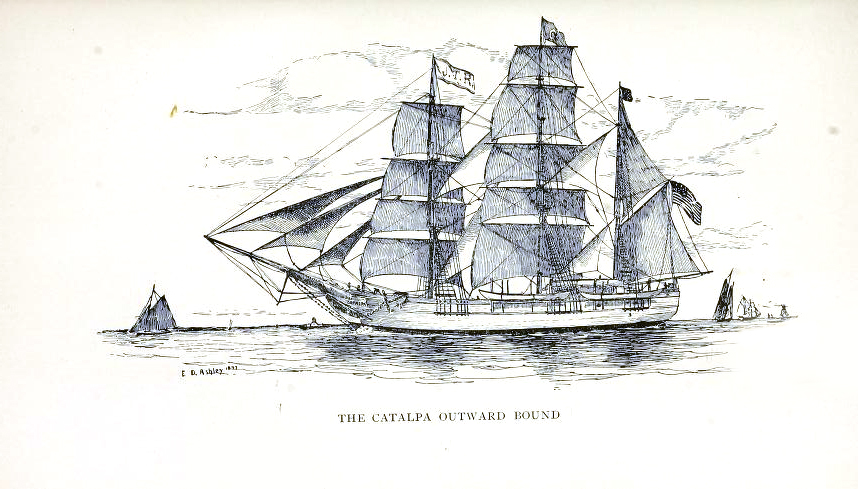

The ship chosen for the journey to Australia was the Catalpa.

Leaving New Bedford in Massachusetts in 1875, the crew who had been hired as a whaling crew had not initially been told about the bigger mission.

They spent five months whaling in the Atlantic before docking in the Azores, offloading whale oil and replacing crew who had become sick or deserted.

The plan unfolds

It was another five months until the Catalpa reached the western coast of Australia.

Two Irish men had travelled there ahead of time, under aliases, to make arrangements required for the ploy to work.

While pretending to be US businessmen, one was able to inform the prisoners of the details of the plan, while another arranged for telegraph lines to be cut on the day of the escape.

O’Byrne says many of the authority figures in the colony were preoccupied a distance from Fremantle that day.

“They chose Easter Monday, which was Perth Regatta Day, so it was a big social event on the colonial calendar,” she says.

The prisoners’ freedom depended on several situations going their way.

O’Byrne says the six men had to initially abscond from the work they were doing outside of the prison.

“One was painting someone’s house, one was working in a garden somewhere, they were all working around Fremantle on the day of the escape,” she says.

Once away from their duties they travelled on horseback and in the back of a buggy about 30km down the coast to Rockingham.

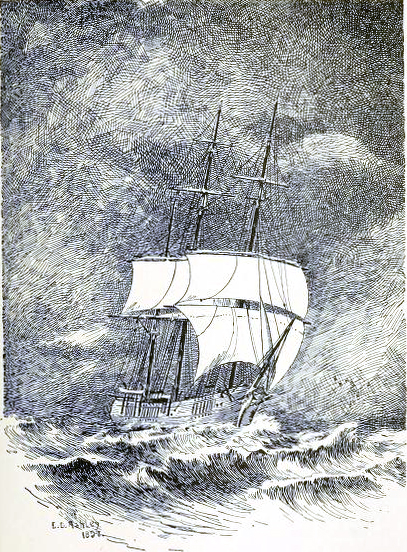

However, when the prisoners were spotted on the beach about to board a rowboat out to the Catalpa, authorities were alerted.

As the authorities worked on getting a search boat out to find the prisoners, the winds blew the rowboat off course. By the time the search boat came across the Catalpa and the authorities demanded any prisoners be released, the crew were not lying when they said they had no prisoners on board.

“Fortunately the waves were big enough that this little rowboat could be hidden,” O’Byrne says.

By this point, the authorities’ boat was running out of coal so it had to leave to load back up, giving the prisoners on the rowboat the opportunity to get back to the Catalpa.

While the authorities were re-coaling, the governor having finished his day at the regatta and being informed of the situation, boarded the boat and headed back out to find the prisoners.

“They steamed out to them and the governor says, ‘We know you have prisoners on board.’”

O’Byrne says the governor warned if they did not give up the prisoners, they would fire on the ship to destroy its sail.

“So Captain Anthony says, I am in international waters and if you fire on me you’ll be firing on the United States of America.”

“It just happened that the Governor had previously been a governor in Canada and had got into great difficulty when he challenged a boat in international waters.”

The authorities ended up turning around and returning to Fremantle.

A successful mission

After a four-month journey, the Catalpa sailed into New York, where the Irish-American community celebrated.

Even though he was technically considered a ‘pirate’ and was unable to go to sea anymore, Anthony was well-respected in his community for his role in helping the Irishmen escape.

He ended up working in the boat harbour at New Bedford checking the papers of all the boats coming in and out.

In Australia, the story of the Catalpa rescue mission and the spirit of those involved has been revived along the very coastline the Fenian Six escaped from.

After an inaugural event in 2023, the Catalpa Adventure Festival held in Rockingham in April marked 148 years since the prisoner’s escape took place.

Ryan hopes to be part of the event in 2026 when he visits to mark the 150th anniversary.