After World War I, when pressed by a journalist to nominate the bravest person under his command, Australian military commander General Sir John Monash named war photographer George Wilkins and likened him to Lawrence of Arabia.

A century later, perhaps one of the most difficult things to understand about the man who came to be Sir Hubert Wilkins, is his place in Australian history. He defies categorisation: he was an outstanding polar explorer, pioneer aviator, war photographer and environmentalist, as well as a mystic – and a champion for the rights of First Australians.

Left to right: Wilkins sits for a portrait in Sydney, c.1911. Wilkins taught himself photography and worked in Australia’s early cinema history; Wilkins poses for a portrait before competing in the 1919 England–Australia Air Race. Mechanical problems forced his plane down in Crete. Image credits: courtesy Ohio State University; Private Collection

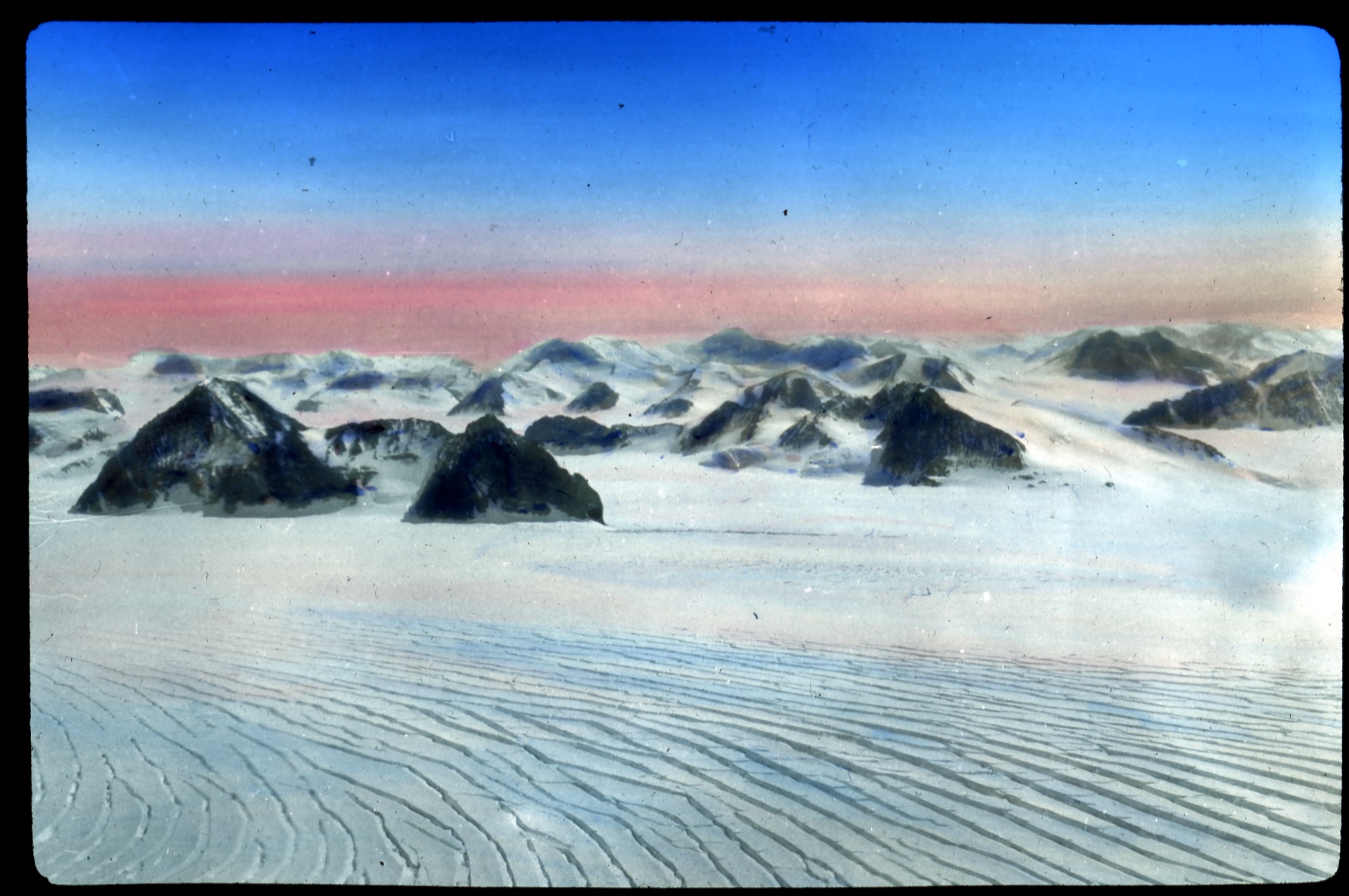

As an explorer, Wilkins went to Antarctica nine times and was responsible for revealing more unknown areas of the most southern continent than all the explorers of the Heroic Age combined. To Earth’s north, he was the first to fly an airplane across the top of the world, and he revolutionised Arctic travel in 1931 when he mounted a submarine expedition to the North Pole.

In his role as war photographer, Wilkins was assigned to work with Australia’s official war correspondent, Charles Bean, at the Western Front in 1917, capturing the photographic record of the Anzacs that Bean wanted. Despite refusing to carry a gun, Wilkins was a war hero who was twice mentioned in dispatches, received the Military Cross for bringing wounded men back from No Man’s Land, and received a bar to the Military Cross for leading American soldiers in an attack against a German machine-gun nest – the incident that earned Monash’s praise. When Monash wanted to nominate him for the Victoria Cross, Wilkins asked him not to, earning Monash’s description as “aggressively modest”.

As an aviator, Wilkins became world-famous for his pioneering flights in both airplanes and airships. As a humanitarian he argued that First Nations people of Australia and the Arctic were, in many ways, more civilised than so-called advanced nations that constantly went to war. He proposed that humanity could raise itself to what he described as “a higher state of civilisation” by better understanding and caring for the environment, a judgement based on his years spent living in remote areas of Australia and the Arctic.

Normally, any number of Sir Hubert Wilkins’s exploits would ensure his place in Australian history, but, remarkably, many people have still not heard of him. And despite Wilkins spending a lifetime in the public eye, even today biographers and historians are confronted with conflicting information, seemingly fanciful tales, and occasions when Wilkins appears determined to keep his activities secret. To understand why, it’s necessary to have a brief knowledge of the life of Sir Hubert Wilkins, and what happened to his enormous legacy of photographs, films, artefacts and written records.

WILKIN’S WORDS ON…

Unpublished manuscript, c.1930

Living with Indigenous Australians, in 1924

For four days and nights they tried to get away from me, and I stuck right with them. When they ran, I ran. I would sleep a nod or two, wake up to see them sneaking away, and I would be right after them. Finally, they gave up and we came to their camp. The camp was nothing but a place where they were staying. There were no women or children in it. The women’s camp was at a little distance, and I knew better than to go near it or even look at it. I stayed with these people for two months travelling with them wherever they went and camping with them at night. During this time, I went on with my work, of course. This amused them all. They decided I was crazy, because I was going around getting things I could not eat, and putting them in jars. I found when travelling with the Aborigines of Australia and with the Eskimo, people who are considered to be among the lowest of civilized people, that they didn’t want to have anything to do with our sort of civilization. Not once they saw how we handled our ideas. I always found them law-abiding, chaste and moral.

George Hubert Wilkins was born on the edge of the Australian outback at Mount Bryan East, South Australia, on 31 October 1888. He was the youngest of 12 – or possibly 13 – children (records are incomplete), born to ageing parents who struggled to eke out a living from land with insufficient rainfall. As a teenager, Wilkins’s parents took him to Adelaide, where he began an apprenticeship as an electrical engineer. He travelled to Sydney in 1909, where he bought his first cameras (both moving and still) and worked in Australia’s early cinema industry. He travelled to England in 1912, then filmed the war in the Balkans from the Turkish side before sailing on his first Arctic expedition in 1913. After the expedition ship sank, Wilkins spent three years exploring the region north of Canada and learning to survive on the ice.

In 1916, after hearing about the war in Europe, he returned to Australia and enlisted as a pilot in the Australian Flying Corps. He was dispatched to France, where, for the next two years, he was one of Australia’s official war photographers. At the end of the war he competed in the England–Australia Air Race, sailed on the Quest with Sir Ernest Shackleton, then spent two years in remote areas of Australia recording Indigenous Australian life. In 1925 Wilkins went north again to explore the Arctic, and in 1928 was knighted for the first airplane flight across the top of the world.

Left to right: Wilkins at his home in Pennsylvania, surrounded by taxidermied penguins. The adventurer was a self-taught taxidermist; Wilkins doffs his hat as he departs on a diplomatic tour of Southeast Asia in 1940. Image credits: courtesy Ohio State University; Bob Mayer

A year after he was knighted – and for reasons still unknown – Wilkins began asking people to refer to him as Sir Hubert, rather than Sir George. The change coincided with his marriage to Suzanne Bennett, an Australian actress working on Broadway in New York. The pair never lived together permanently and the marriage produced no children.

In 1928 and 1929 Wilkins explored Antarctica from the air and flew around the world in the Graf Zeppelin – a German hydrogen-filled airship. He then mounted an audacious plan to travel in a submarine, under the Arctic ice, to the North Pole. While he succeeded in getting under the ice, the decrepit WWI submarine, combined with a mutinous crew, prevented him from reaching the Pole.

Having spent all his money on that expedition, and with the world in the grip of the Great Depression, Wilkins pursued work for wealthy American explorer Lincoln Ellsworth. Managing his expeditions took Wilkins to Antarctica a further four times. He also spent a year looking for lost Soviet aviators in the Arctic, and was personally rewarded for his efforts by Joseph Stalin. During this period, he conducted experiments in mental telepathy and explored the powers of the subconscious mind. Wilkins returned to Australia in 1939, hoping to set up an Antarctic research program. At the urging of the famed Australian geologist and Antarctic explorer Sir Douglas Mawson, the Australian government refused to support the plan, so Wilkins returned to the USA, where he bought a small farm outside Montrose, Pennsylvania. Wilkins’s wife, Suzanne, lived at the farm, along with his personal assistant, Winston Ross. Wilkins, however, continued his restless wandering, working as a spy for the US Office of Strategic Service during World War II. After the war he continued as a consultant to the US Armed Forces, training soldiers in polar survival.

WILKIN’S WORDS ON…

Speech made during WWII

Civilisation

Civilization means to me, steps from barbarism to refinement. It means that the weak will have rights as well as the strong, and that science will have greater consideration and will produce the benefits that we will use in our progress toward universal culture. In civilization we can’t expect the law of force and aggression will lead to progress. Of course, I think civilization is still, in spite of its progress, just a figment in the mind of each individual. Because the civilization that you understand and that I understand may not be the same. Now I have travelled in many countries and in each country they had their own idea of what it means to be civilized. I believe the Democratic countries have, by their advantage of a certain amount of security and co-operation, reached the highest degree of civilization. And I believe the Democratic countries will agree that we must work together in putting before the world our sort of civilization, rather than have other people, who perhaps have not had our advantages, progress with their ideas.

Wilkins died alone in a hotel room in Massachusetts on 30 November 1958. He was held in such high regard by the Americans that the US Navy carried his ashes in a nuclear submarine to the North Pole, where they were scattered on 17 March 1959.

At the time of his death, Wilkins’s personal lifetime of memorabilia was stored at his Pennsylvania farm. The collection included tens of thousands of photographs, thousands of letters and many personal journals and artefacts, along with the gifts, medals, certificates and awards that world leaders, dignitaries and learned societies had showered upon him. The collection also held souvenirs of almost every aspect of Wilkins’s remarkable life, from his boarding pass when he flew on the Hindenburg to Inuit bows and hunting gear; from his primary school records from SA, to cutlery carried on his Arctic submarine. The size and scope of the Wilkins collection at the time of his death is impossible to comprehend. Unfortunately, it was stored haphazardly in cardboard boxes, stacked floor to ceiling, in a barn, the roof of which leaked, so that by 1958 much of the collection was beginning to rot.

(clockwise top to bottom) The contents of a box of Wilkins’s material, discovered by Jeff Maynard in a private collection in 2014; Wilkins married actress Suzanne Bennett in 1929, although they never lived together permanently; The Wilkins Homestead at Mount Bryan East, in SA, was restored and opened to the public in 2001. Image credits: Jeff Maynard; Private Collection; Jeff Maynard

Following his death, the fate of the material worsened. First, Suzanne went through it, destroying all references to other women in his life. Wilkins enjoyed female company, and was engaged to be married at least once before he finally married Suzanne. It is difficult to estimate how much material she destroyed, but it must have been substantial. In the 1940s, Wilkins had written a semi-fictitious account of his life, intended to be serialised for radio. He called it True Adventure Thrills and it included accounts of fighting duels, narrow escapes from firing squads, being captured by slave traders, finding beautiful female stowaways on his expeditions, and many other exciting adventures. After Wilkins’s death, when author Lowell Thomas wanted to write his biography, Suzanne gave him a copy of True Adventure Thrills. Not knowing any better, Thomas published the unproduced radio serial as an account of Wilkins’s life (titled Sir Hubert Wilkins – His World of Adventure), which has remained a standard reference on the subject since. Even recent books about Wilkins struggle to distinguish between fact and fiction.

Having partially destroyed Wilkins’s legacy, then misled the world by authorising a fanciful account of his life, Suzanne died in 1974 and bequeathed the farm in Pennsylvania to Winston Ross, Wilkins’s former assistant. Shortly after, Ross married Marley Shofner, a yoga teacher from California, who already had two sons to two previous husbands. Marley and Winston Ross decided to set up a museum to the Australian explorer, but when few people seemed interested in travelling to a remote area of Pennsylvania to see it, they funded their lifestyle by selling material. Two large collections of Wilkins’s polar correspondence were sold to two polar philatelists, who were amateur postal historians. Following a lengthy and costly dispute with the philatelists, the Rosses paid their legal bills by selling some 80 boxes of material to the Ohio State University for its polar archive.

The Rosses also gave material away. For example, Dick Smith, who has always been an admirer of Sir Hubert, visited the Pennsylvanian farm in 1982 and brought Wilkins’s car, a 1939 Chevrolet, and a polar sledge back to Australia. Other material was simply sold through antique shops in Pennsylvania, or to private collectors around the world. When Winston Ross died, Marley inherited the farm and its contents. She died in 1998 and a dispute between her two sons meant one took some material back to his home in Michigan, while the other took the remainder to his home in Arizona.

WILKIN’S WORDS ON…

Speech, 1938

The influence of the weather

My attention was drawn to the effect and influence of natural things when I was a small boy in Australia. There we suffered from long and unexpected droughts. I believed that if we could get a fore-knowledge of these seasonal conditions that we might be able to tell, not only the graziers who were producing the meat that we needed for our comfort, and the wool and the wheat and other things, but to help the manufacturers as well to produce sufficient for humanity, with certainty, not as we find today, a sufficiency one year, and not enough the next.

People often say, ‘What are you doing in the polar regions?’ It’s because we can only expect to get a greater knowledge of the weather by observing conditions all around the world that I go to the polar regions year after year. Not that the polar regions themselves will offer the secret of weather forecasting, but knowledge from there, co-ordinated with all other information in the world will, I believe, place our scientists in a position to tell the economists what they can do in providing for the security, not only of their own country, but for all of humanity.

Today, various collections of material have been successfully preserved. Some have been added to the Wilkins Collection at Ohio State University, where it’s held in a purpose-built archive and available to researchers. Records relevant to Wilkins’s time on the Western Front and Gallipoli have been brought back to Australia for eventual preservation at the Australian War Memorial. Other material has been donated to the South Australian Museum. Dick Smith, with support from the Australian Geographic Society, had Wilkins’s birthplace at Mount Bryan East restored. It was opened to the public in 2001. More recently, Dick donated the car he brought back from the USA to the National Motor Museum at Birdwood in SA, and the polar sledge to the South Australian Museum.

Much, however, is still in private hands and many of Wilkins’s papers and journals remain unread. The work to understand this remarkable character is continuing, and hopefully in the future, as more is revealed, Sir Hubert Wilkins will enjoy a more prominent place in Australia’s story.

Jeff Maynard has researched and written about Sir Hubert Wilkins for 25 years, locating Wilkins’s material in museums and private collections around the world and working to have it preserved and catalogued. Jeff’s latest book is The Illustrated Sir Hubert Wilkins (Netfield Publishing, 2022). Learn more about Jeff’s ongoing work at jeffmaynard.net