Stories told by Aboriginal Tasmanians could be oldest recorded in the world

Storytelling is an ingrained practice in our cultural history, either as a family custom at bedtime or as a way to share knowledge and traditions from years gone by with younger generations.

But for how long can stories be passed down from generation to generation by word of mouth? A few hundred years? Maybe a thousand?

Try 12,000 years! A new study, led by Dr Duane Hamacher from the University of Melbourne, shows that in Lutruwita/Tasmania, Palawa have a rich oral tradition that tells of geological events and astronomical conditions that stretch back more than 10 millennia.

The findings of the study, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, place these oral traditions among the oldest in the world.

The power of oral tradition

First Nations people have lived in Australia for more than 65,000 years. During this time, they have relied mainly on oral tradition to pass on their knowledge to subsequent generations. However, there has been no real understanding by non-Indigenous people of how long traditions can survive.

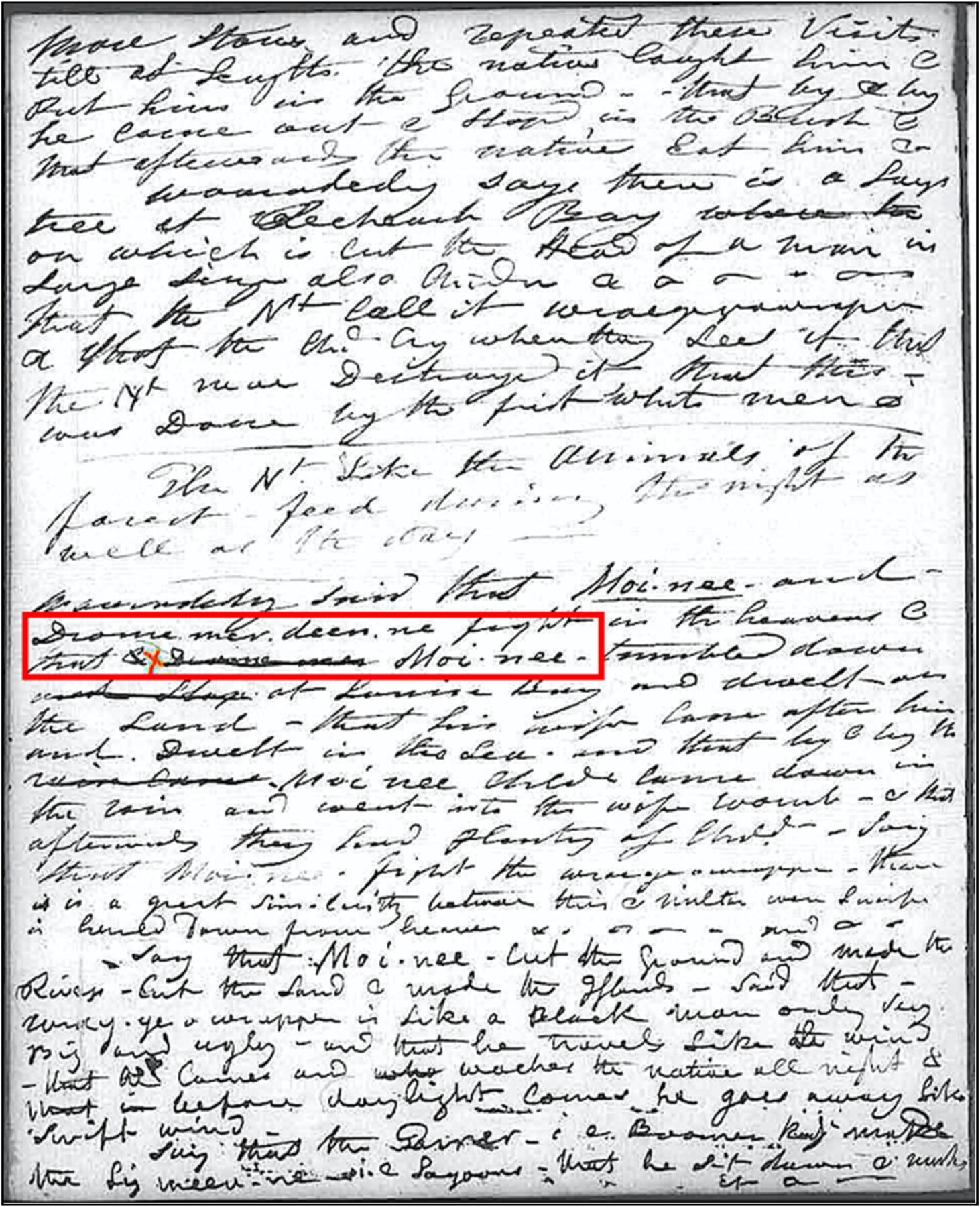

To better understand the process, Duane studied oral traditions from Lutruwita that were recorded by early colonisers in the 1830s. The team focused on oral traditions that described natural events that could be dated scientifically. Their thinking was that, if they could date a natural event that occurred millennia ago that was described in a surviving oral tradition, they could estimate a minimum timeline for how long that oral tradition has existed.

Ancient floods

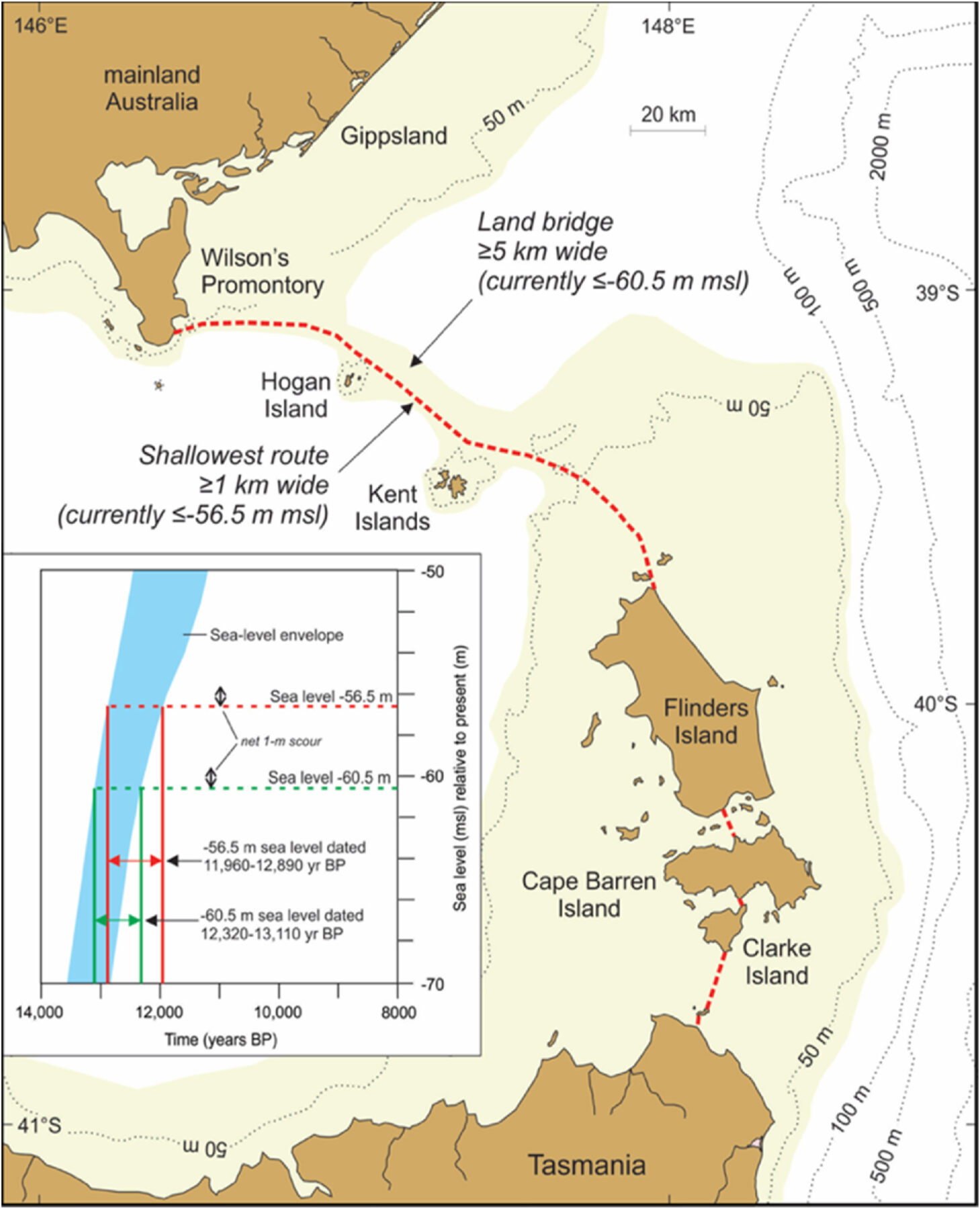

Palawa oral traditions speak about an ancient flood that submerged the land connecting Lutruwita to mainland Australia eons ago.

According to George Augustus Robinson, a government-appointed ‘conciliator’ from the 1800s, Palawa people claimed that their ancestors came to Lutruwita by land from the far north, after which the sea (Bass Strait) formed, flooding the land. Another recorded oral tradition described how:

“…long ago there was land to the south of Gippsland [Victoria] where there is now sea, and that at that time some children of the Kurnai, who inhabited the land, in playing about found a turndun [bull-roarer or musical instrument], which they took home to the camp and showed to the women [which was forbidden]. ‘Immediately,’ it is said, ‘the earth crumbled away, and it was all water, and the Kurnai were drowned.”

With this information at hand, Duane and his team analysed bathymetric and topographic data of the land and sea floor in Bass Strait. They found that the land was flooded around 12,000 years ago.

Star stories

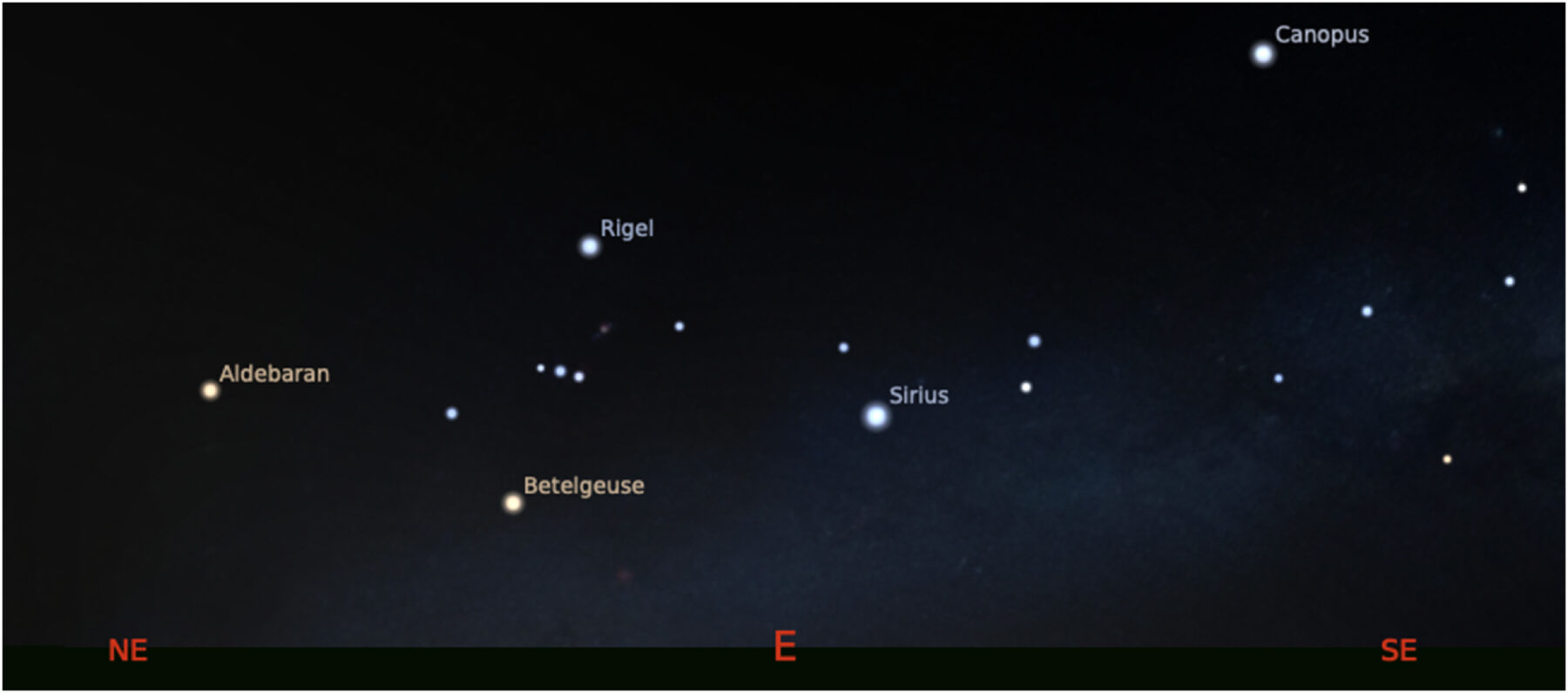

Some Palawa stories also talk about the presence of a ‘Great South Star’, which one Elder said never moved. Another Elder explained how:

“The suns [sic] had their first-born, Moinee, a big strong boy whom they placed south of Trowenna [Lutruwita], over the ice cap. He was the Great South Star. Next day a second son was born, gentle Dromerdene, and they placed him halfway between themselves and Moinee.”

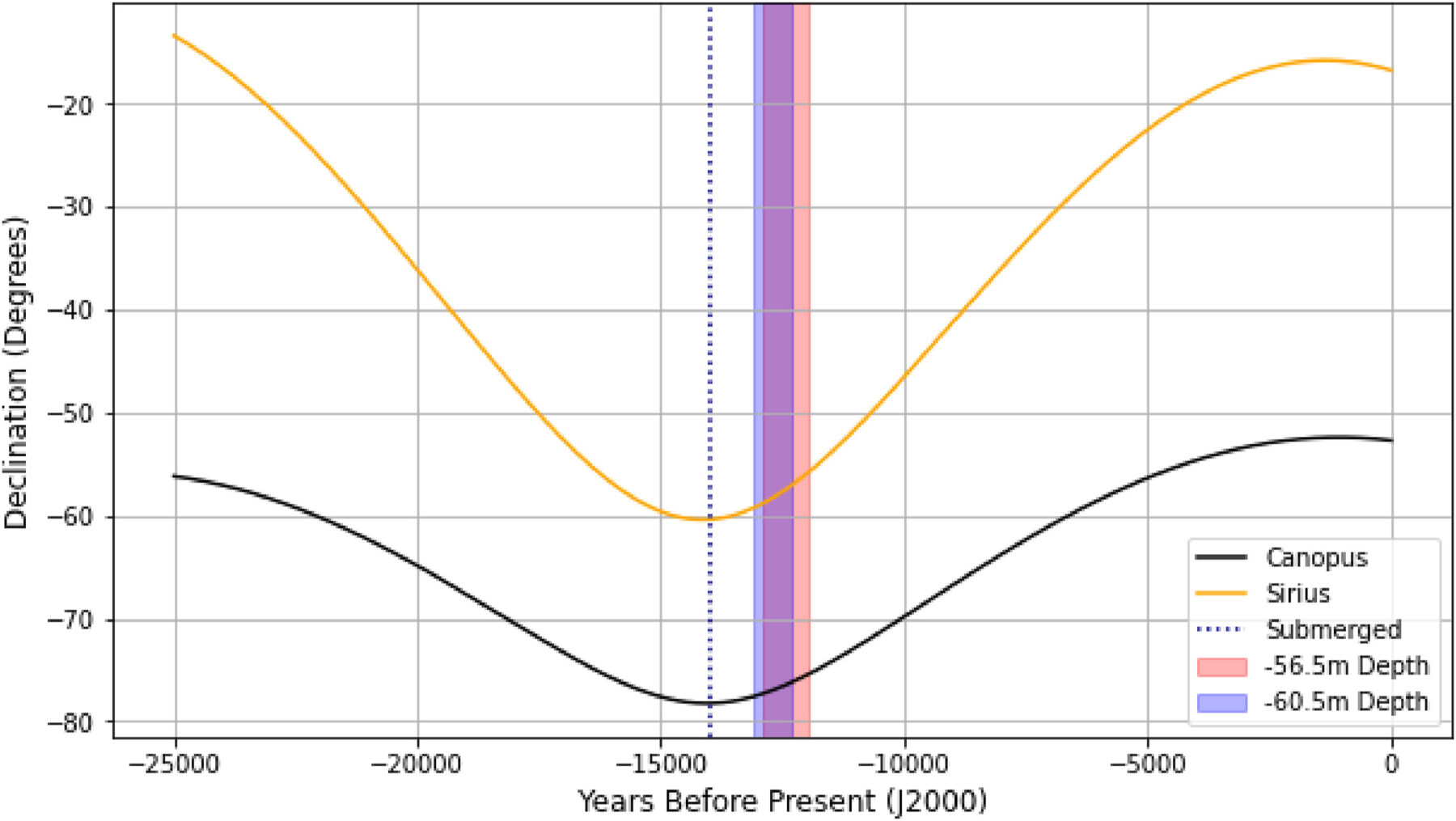

The team then analysed astronomical data to determine the positions of these stars in the ancient past, which the team identified as Canopus (Moinee) and Sirius (Dromerdene). These are the two brightest stars in the night sky.

Their analyses showed that the orientation of the Earth’s axis placed the star Canopus (Moinee) close to the South Celestial Pole sometime around 14,000 years ago. According to their study, at that time, Canopus would have hardly moved over the course of a given night, backing the oral traditions.

Challenging ideas

Overall, the results of this study show that Lutruwita’s oral traditions involving a ‘Great South Star’ and a submerged land bridge could be confidently dated to a timeframe 12,000–14,000 years ago.

“Initially, I was quite surprised,” says Duane. I was sceptical that oral traditions could be passed down for that long. But that is what the evidence showed. Plus, recent research on orality and memory provides a solid theoretical foundation for how and why this is done.”

“Our work uses two lines of evidence to show that oral traditions can be passed down while maintaining vitality for periods exceeding 10,000 years. It is a great example of how natural events and conditions described in oral tradition can be used to provide a minimum age for these stories and help us better understand the nature of orality and deep time memory,” he adds.

Duane says his team will continue working on this path, collaborating with Elders to better understand the Palawa cultural traditions involving astronomy and natural events.

“There is so much to learn if we take the traditions seriously, rather than dismiss them as ‘myth and legend’ as so many have done before,” Duane says.