Defining Moments in Australian History: Founding of the UN

Herbert Vere ‘Doc’ Evatt, external affairs minister in the Curtin and Chifley governments, insisted smaller nations have greater influence in the newly formed UN, making the organisation more egalitarian.

The development of the United Nations began with the Declaration of St James’s Palace in 1941, which was the first joint statement of goals and principles produced by the Allies in World War II. It was signed by representatives of Great Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the exiled governments of Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Yugoslavia and France. Subsequent proposals to replace the old League of Nations with a new organisation gained momentum.

In 1944, Great Britain, China, the USSR and the USA met at the Washington Conversations on International Peace and Security Organization (aka the Dumbarton Oaks Conference) in Washington, DC to draft the organisational structure and procedures of this new body.

Herbert Vere ‘Doc’ Evatt became minister for external affairs when Curtin’s Labor government took office in 1941. Having displayed relatively little interest in foreign policy up to this point, Evatt quickly overcame his lack of experience and eventually had a prominent role in the founding and early running of the UN.

Threatened by Japan’s entry to the war and learning that Britain and the USA had privately agreed on a “beat Hitler first” strategy, Evatt focused on improving Australia’s fighting position in relation to the rapidly approaching Japanese forces. When he discovered that Roosevelt and Churchill had agreed with China on peace terms for the Pacific without consulting Australia, he was furious. He set about formulating an alliance with New Zealand that would form the basis for postwar regional security. Rejection of this initiative by the USA bolstered Evatt’s support for the new international organisation proposed by Britain, the USA and the USSR.

Evatt backed early attempts to build the UN. In supporting the idea of collective security, there was the possibility that less powerful countries such as Australia could have a better say in international negotiations, and might receive protection against aggression. However, the proposal produced at the Dumbarton Oaks Conference concerned him; he believed it concentrated power in the hands of too few. There was little or no role for small nations to play, and Evatt thought this would discourage their involvement.

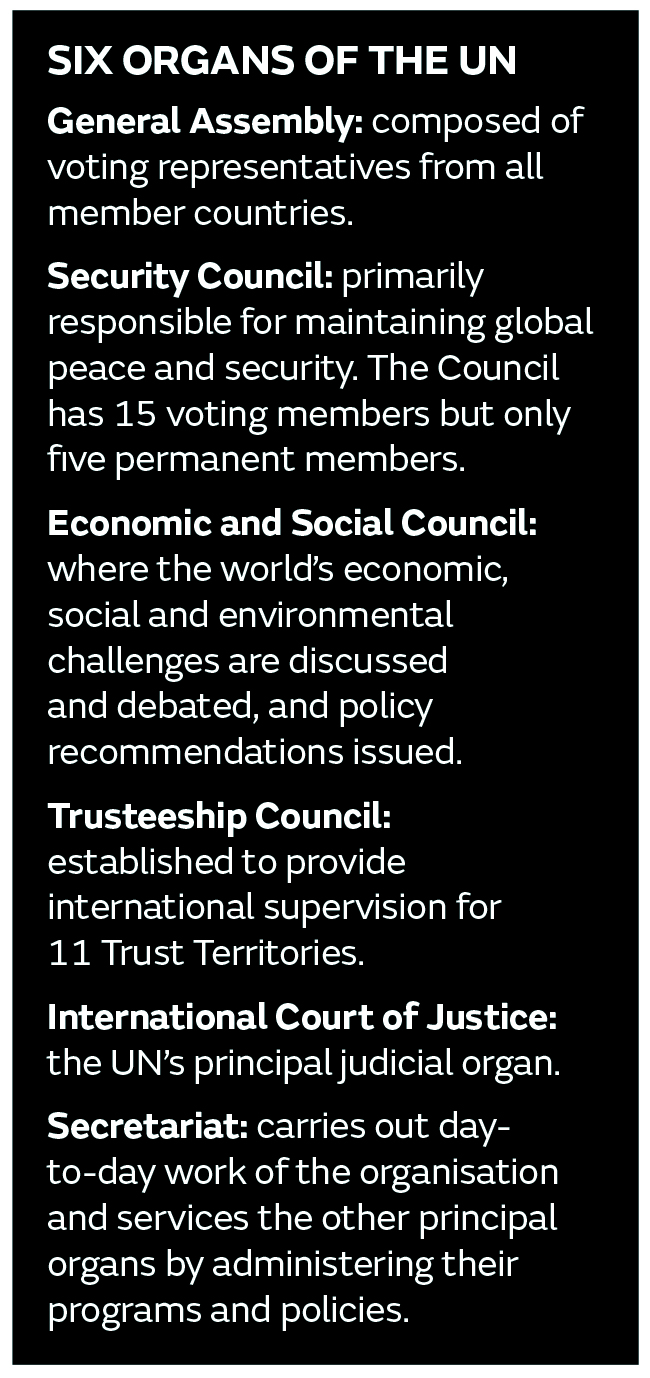

During the San Francisco Conference in 1945, the Australian delegation suggested a range of amendments to the Dumbarton Oaks proposal. With the support of other smaller nations, Evatt succeeded in enlarging the scope of the General Assembly, the main deliberative organ of the UN, so its powers were closer to those of the Security Council.

His second major achievement was a greater acknowledgement of the social and economic roles of the new organisation. Member nations pledged to work towards better living standards, full employment and freedom for all.

Evatt’s attempts to reduce the veto power of the Security Council were unsuccessful. Although amendments were put forward, the USSR, in particular, refused to give any ground.

Evatt was president of the UN General Assembly in 1948–49, during which time he was instrumental in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and played a prominent role in the creation of Israel.

Because of Evatt’s passion displayed at the San Francisco Conference, the General Assembly voted for Australia

to have a non-permanent seat on the Security Council

in 1946–47.

‘Founding of the UN’ forms part of the National Museum of Australia’s Defining Moments in Australian History project.