Now a ghost town, Eucla owes its hey day to the telegraph station

The ability to transmit information almost instantaneously held a special significance for the isolated settlers in the Australian colonies.

The East–West Telegraph line, built in 1875–77, was the final link in Australia’s telegraph infrastructure and connected all five colonies. The largest station of the East–West line was Eucla Telegraph Station, located 11km west of the Western Australia–South Australia border.

When the weatherboard station began operations on 9 December 1877 it was staffed by four male telegraphists, who lived in nearby tents and wooden cabins. In 1898 the station was rebuilt in stone, with separate quarters for the 26 telegraphists and their families.

The station’s growth was due largely to WA’s gold boom in the 1890s, because operators retransmitted urgent messages for sharebrokers to Kalgoorlie, Boulder and other goldfields in the western colony. Despite its remote location, Eucla was one of Australia’s busiest stations outside of the capital cities. It received up to 600 telegrams daily.

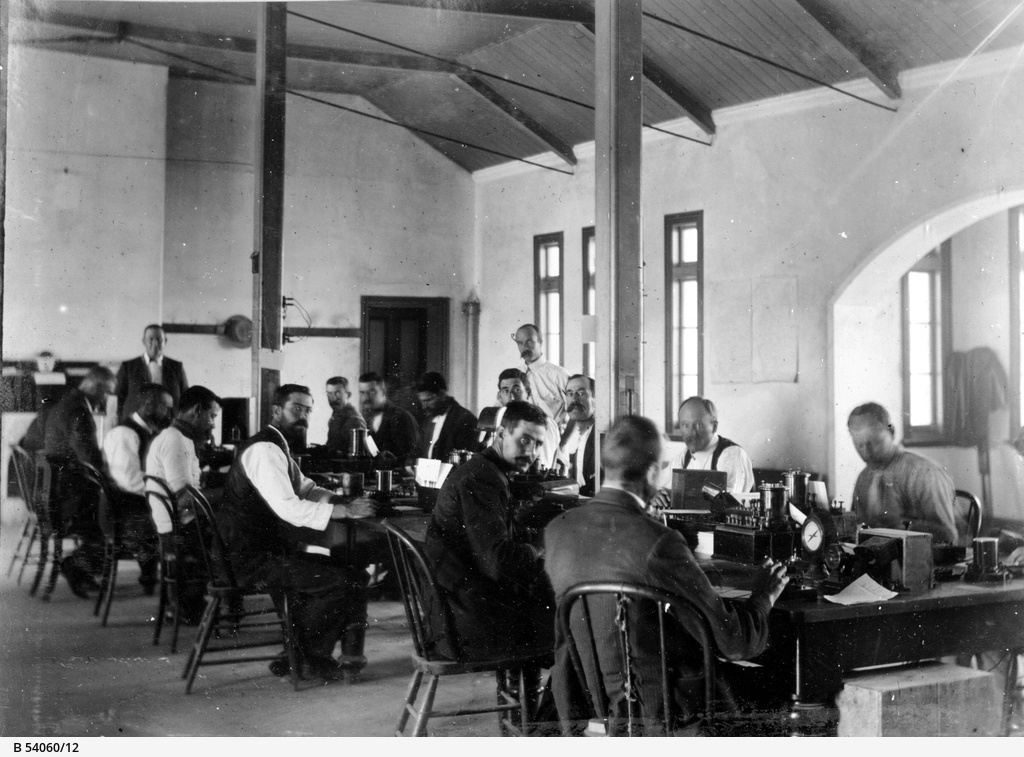

Eucla Telegraph Station operated as two colonial terminal stations because SA and Victoria used American Morse code, while WA and the remaining colonies used International Morse Code. The station was staffed by both WA and SA telegraphists, who worked on opposite sides of a wooden table that ran the length of the room.

At the time, the telegraph station was incorrectly believed to straddle the WA and SA boundary. A wooden partition divided the workers into their respective borders, with “boundary holes” for operators to pass through transcribed messages for retransmission. Although operators worked in the same office, they adhered to the time zones of their respective colonies, meaning WA was an hour behind SA until 1899, at which point SA advanced its clock by another 30 minutes. After Federation in 1901 the partition was removed.

Despite its transient population, the small community at Eucla was tight-knit.

“[The conditions] were a stern test of ambition and ability, demanding self-reliance and creating a wonderful spirit of camaraderie and fellowship among the men working and living together in such a remote place,” recalled Frederick G. Simmons, who worked at Eucla Telegraph Station 1898–1925. “They made us ‘blood brothers’, built lifelong friendships and stored up a host of memories for the days when Eucla’s work was finished.”

The closest towns were Fowlers Bay, 335km to the east, and Esperance, 700km west. In their spare time the men played sport, shot kangaroos and fished and swam in the Great Australian Bight.

The telegraphists were well educated and their work carried prestige.

In 1898–1900 the station produced a newspaper called The Eucla Recorder. It published reports on former Eucla staff and other news and editorialised on the big issues, including women’s enfranchisement, the Boer War and the constitutional referendums in the lead-up to Federation.

In the 1890s there were new arrivals at Eucla Telegraph Station: rabbits.

In 1859 pastoralist Thomas Austin released rabbits on his property in Victoria; by the 1890s, populations had spread and multiplied into plague proportions. Besides the telegraph station, the rabbits took up residence on the Nullarbor Plain.

Within a few short years, the rabbits had destroyed the scrub and vegetation on the dunes, loosening the sand.

The Eucla Telegraph Station ceased operation in 1927 when new telegraph wires were built along the Trans-Australia Railway.

Today, Eucla is a ghost town, its ruins slowly but surely disappearing under the encroaching dunes.