Dulcie Holland’s early piano lessons as a six-year-old always started with an impromptu botany lesson. She would take some of the native flowers that flourished in her garden along to her piano lessons, where her teacher’s father would identify them. Throughout her life she took pride in reciting the curly botanical names of Australian plants.

Decades later, she would play her own role in educating immigrants about this strange and faraway land. She composed the music for a series of postwar documentaries that promoted Australia as a place to live and educated would-be migrants about the virtues of their new home.

Dulcie Holland was my grandmother, and it was through discussion of these films around the family dinner table in suburban Sydney that I first recall learning about her musical career. The notion of “new Australians” sailing from Europe and watching these films on board ships sounded impossibly exotic to me.

Between 1945 and 1965 more than 2 million people emigrated to Australia – mostly from war-torn countries – as part of Australia’s great “populate or perish” push. Although the government initially targeted Great Britain, it quickly realised that to sufficiently increase the population they would have to widen the net. Arthur Calwell, minister for information (1943-49) and Australia’s first minister for immigration (1945-49) embarked on a program of promotional documentaries aimed at recruiting more immigrants.

The films were initially made by the Department of Information’s Film Division, which had wartime filmmaking experience, before becoming part of the Australian News and Information Bureau within the Department of the Interior. In 1956 the Film Division was renamed the Commonwealth Film Unit, the precursor to Film Australia.

They were shown in overseas embassies and on migrant ships heading to Australia. Because the films were mostly 35mm gauge, they were suitable for showing as shorts in cinemas and were particularly popular in the USA. Some companies, such as Shell, made similar films to attract workforces for their projects.

In the mid-20th century, Australia was at a pivotal point in its history of modernising and building. The films were about daily life, local community and industry. No matter the subject, the focus was on escaping the deprivations of battle-scarred Europe and coming to a progressive and stable new land with good housing, education, medical facilities, transport and jobs. Trade unions also featured, to demonstrate to prospective immigrants that Australia was a safe country for workers who could enjoy freedom of speech.

Dulcie composed music for more than 40 films, including 13 for the Department of the Interior. It became one of the highlights of her long and illustrious career as a pianist, composer, teacher and adjudicator.

She was already known in musical circles. She’d gone from being a promising young student at the New South Wales State Conservatorium of Music, under the tutelage of Frank Hutchens and Alfred Hill, to travelling to London in 1937 to study at the Royal College of Music. There she won a prestigious scholarship but had to relinquish it and return home when war broke out in 1939. Back in Sydney, Dulcie married schoolteacher and amateur musician Alan Bellhouse, and they had two children. During the 1940s she worked as a teacher, recitalist and arranger.

She got her start composing film music on the 1946 feature Time Off through her professional association with radio musician Clive Amadio. The film did not have a strict deadline, which allowed Dulcie to learn the ropes without pressure. The government producers saw the film and were impressed with Dulcie’s contribution. In 1949 they hired her to compose the music for some of their new documentaries. She was one of the few women employed on production teams at that time.

From there, Dulcie’s film scoring career took off. She wrote music for films on subjects as diverse as weddings, shearers, weather reports, farmers, journalists, deep-sea pearlers and the food industry. Original music was seen as essential to help convey an upbeat, optimistic mood about Australian life. Lyrical music accompanied pastoral or sea scenes, and bright, rhythmic sounds were used for sequences showing the routines of daily life.

Deadlines were tight and the briefs exacting. First, she would watch a largely completed film a few times over. Then she studied the list of scenes in the film and jotted down ideas about mood and appropriate instruments. The music needed to accompany the action on screen precisely, right down to the second. She had limited numbers and choices of instruments at her disposal, but occasionally there was more leeway.

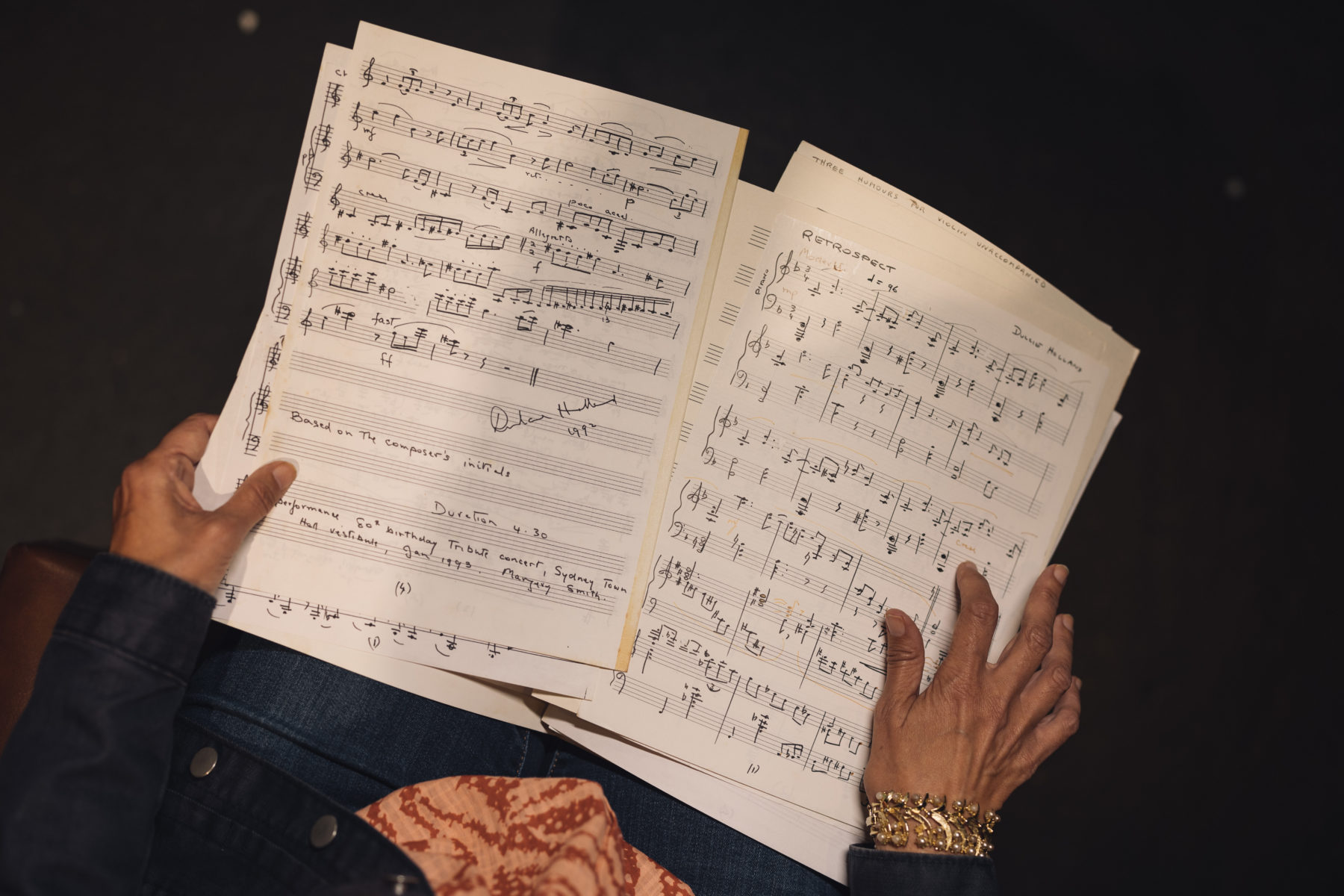

Whereas modern composers use music writing software, Dulcie would work on paper with pencil, eraser, stopwatch and metronome. The work was a challenge. She was a doodler at the piano and self-confessed slow writer. “This is strictly stop-watch music but I find it fascinating, even though my favourite chord may be faded out while someone talks on wheat.”

Combining deadline-oriented work with family life was no mean feat, but Dulcie was thrilled to get the work. “I loved doing it because it gave me an outlet and composers don’t get many outlets for writing music. It made me feel useful in a musical sense.”

When composing, she preferred to work in the morning when she felt fresh. In 1957 she told the ABC Weekly that once the children left for school she would shut off all distractions, scoff chocolate biscuits for lunch and try to ignore the telephone.

Her output is especially notable, given it was rare for women to combine a young family with a career in that era.

The documentaries depict an Australia that has all but disappeared. It is culturally homogeneous, male-dominated, and the people featured are neatly dressed, often with hats and gloves. Watching the films today is to step back in time.

The government continued making such films until the mid-1970s, but Dulcie’s association ended in the 1960s, after which she started work on the Master Your Theory and Musicianship series for students, for which she is best known. She kept composing and, over time, incorporated uniquely Australian themes into her music. Perhaps the work on the film scores was a springboard for her to compose music about her homeland. She wrote, “I think we have come to a great realisation of the importance of our own country, not the importance of it in a jingoistic way, but of the value of the things which belong to Australia which don’t belong to any other country.”

She wrote a collection of children’s songs called Young Australia and, a long-time lover of poetry, she started setting Australian poems, rather than the English and Irish poems of her childhood, to music.

Owing to burgeoning interest in previously overlooked Australian female composers, there is growing acknowledgement of Dulcie Holland’s contribution as a composer, rather than solely as a music educator.

Possessed of a warm and modest personality, she would not have sought attention for herself, but rather would have been delighted that people were listening to Australian music. But I wonder how her film scores might have sculpted the emotions of so many people about Australia, either while enjoying a Saturday night at the movies in 1950s USA, or filled with hope and anticipation on board an immigrant ship bound for a distant land.

Popular films with music scored by Dulcie Holland

Double Trouble (1951) – directed at a domestic Australian audience, this was one of the few films made to help people understand “new Australians”. In an interview in 1987, director Lee Robinson (who also produced Skippy the Bush Kangaroo) said, “The message was: Have a thought about the problems of people who have a language barrier. Be more prepared to help.” The film used professional actors, which was rare for that time. The story centred around two Aussies, Stan and Bob, who criticise immigrants who can’t speak English. The two men then find themselves “magically transported to a foreign country” where they can’t speak the local language. The film was shown at the Edinburgh International Festival and is regarded as showing the beginnings of multiculturalism as government policy.

The Melbourne Wedding Belle (1953) – described at the time as a “romantic fantasy”, this documentary was made to promote the 1956 Melbourne Olympics. It was produced by acclaimed filmmaker R. Maslyn Williams. Narrated in rhyming verse, it shows the preparations for the wedding day of “Jane Alma Rhode” and “Hugh Collins Street” against a backdrop of Melbourne icons. Years later, at the 1996 International Documentary Conference, the director, Colin Dean, described the film as innovative because it used Ferraniacolor, a colour film stock developed in Italy and not often used in Australia.

Paper Run (1956) – shows a newspaper run in Sydney’s Northern Beaches, with a bright whistling tune, rhumba music and birdcalls to accompany the scenery. The film opens with the Daily Telegraph print run at Consolidated Press and follows Don Tweedie (who ran Newport Newsagency at the time) in his yellow Vauxhall Vagabond convertible delivering newspapers. Actual Northern Beaches identities featured, including wheelchair-bound George Shelley, one of the many polio sufferers of that era. Paper Run was shown in New York cinemas as a short before feature films and also in Australian cinemas.