Lasseter’s Reef: Will it ever be found?

IN THE FIRST issue of Australian Geographic, in 1986, the magazine’s founder, adventurer and entrepreneur Dick Smith, wrote: “There are six books published on Lasseter’s Reef and a major documentary. I’ve thoroughly researched the lot and I still have a completely open mind.”

The fabled gold-rich quartz reef was said to have been found somewhere west of the MacDonnell Ranges, in Central Australia, by Harold Lasseter in 1897.

Since then, it has become a thing of legend.

During the past three decades alone, it has featured in at least 10 AG stories, been the subject of numerous books and films – including the 2012 documentary Lasseter’s Bones – and inspired countless adventurers to launch expeditions to Central Australia in search of the long-lost gold quarry.

To date, however, the reef, which Lasseter claimed was laden with gold and measured some “seven miles [11.3km] long, four to seven feet [1.2–2.1m] high, and 12 feet [3.7m] wide”, has remained elusive.

Today, Dick confirms that while he “remains quite sceptical about its existence” he also “won’t completely rule it out”.

Not quite so optimistic about the chance of Lasseter’s mythical gold seam ever being found is Geoscience Australia, the national agency for research into the geology and geography of our country.

“Other than the claims made by Lasseter and the various parties that subsequently looked for the reef, there is no independent evidence that Geoscience Australia is aware of a gold-bearing quartz reef in the areas to the west and south-west of Alice Springs towards and across the South Australia and Western Australia borders,” a spokesperson for the agency says.

Geoscience Australia pours further cold water on the possible existence of the reef, which Lasseter claimed he discovered when he was just 17 years old during a prospecting expedition he later said he was forced to abort after his horses died and he ran out of water.

“Lasseter’s numerous mistakes in Central Australian geography and also in the layout of Alice Springs, recorded in several published books, cast considerable doubt on his veracity,” the spokesperson says.

“Even if he suspected, feared, or knew his samples were fool’s gold, like pyrite or iron sulfide, he said they were gold, for his own reasons.”

Two contemporary books cast much doubt on the existence of Lasseter’s Reef: Murray Hubbard’s 1993 investigation of Lasseter’s life, The Search for Harold

Lasseter: The True Story of the Man Behind the Myths; and historian Chris Clark’s 2015 Olof’s Suitcase: Lasseter’s Reef Mystery Solved.

Those who have followed Lasseter’s story closely will be aware that prior to the 1930 Central Australian Gold Exploration (CAGE) expedition to ‘rediscover’ the lost reef, Lasseter claimed to have visited Central Australia on three separate occasions – in 1897, 1900 and 1911.

“Murray [Hubbard] is the man who turned this story around,” Chris Clark says. “He proved in his book that before the 1930 expedition, Lasseter had never visited Central Australia; his conclusion was that the story of the reef was made up.”

Chris’s own extensive research supports Murray’s findings.

“Records dug up by Murray proved Lasseter was in a reformatory school in Packenham, Victoria, in 1897, and although he absconded in mid-October, that wouldn’t have given him time to find a gold reef in Central Australia in the same year,” he says.

So, if Lasseter had never previously set foot in Central Australia, how did he convince a consortium in 1930 to fund the CAGE venture, the largest inland expedition since that of Burke and Wills in 1860, to find a reef he knew didn’t exist?

Just as poignantly, why did he carry on with the search to the point that it cost him his life?

The answer to the first question is now well accepted among Lasseter aficionados.

“It was the Great Depression; people were battling to put food on the table for their families.

“The opportunity of finding a gold bonanza so big that it would lift Australia out of the economic doldrums proved irresistible,” Chris says. “Lasseter was also desperate to feed his own family.”

For Chris, the key to unlocking the second part of the riddle lay in the most unexpected location: a long-forgotten suitcase hidden on the other side of the world that belonged to Chris’s late Swedish grandfather, Olof Johanson, who spent many years dingo-trapping in Central Australia in the early to mid-1900s.

For much of his life, Chris had little more than a passing interest in the Lasseter case, but that all changed when Luke Walker, director of Lasseter’s Bones, contacted Chris’s mother in 2010 alerting her of two pieces of correspondence that provided a tangible link between Olof and Lasseter.

“One was a telegram sent on 16 June 1930 by Olof on receiving a letter from Lasseter probably in reply to a letter Olof had sent stating that he also knew the location of the reef,” Chris says.

“The other was a letter from July 1930 in which it appears that Olof was responding to an approach by Lasseter to assist him in the capacity as a guide in trying to ‘relocate’ the lost reef.”

During a trip to Sweden in 2014 to visit his grandfather’s grave and meet surviving members of his family, Chris was gifted the suitcase that Olof had carried with him when he returned home from Australia 65 years before.

“Inside was a collection of photographs that showed conclusively that he must have been out in Central Australia in 1928–29,” Chris says.

He adds that this photographic evidence was supported by the timely release of the personal papers of Neville Wolff, a man who worked with Olof in Kalgoorlie in 1929–30.

The papers reveal that Olof told Neville he had stumbled upon a stone reef in the Rawlinson Ranges, in Central Australia, upon which an old “shallow shaft” had been sunk.

“It was only when he read that Lasseter’s expedition was being assembled in Sydney that Olof must have connected the dots, and began to think that he might have stumbled on the diggings that Lasseter claimed to have made when he first discovered the reef,” Chris says.

“It appears that my grandfather was yet another sucker taken in by Lasseter’s swindle.”

ARMED WITH INFORMATION on Olof’s gold find, much to the chagrin of other members of the 1930 CAGE expedition, Lasseter changed his story about where he had found the reef.

Instead of heading to the West MacDonnell Ranges, he demanded they search much further south-west, near the Rawlinson and Petermann ranges.

“This behaviour was totally consistent with the fact he wasn’t looking for the reef he originally told everybody about, for he knew that was total rubbish,” Chris says.

Instead, Chris suspects Lasseter was looking for the reef Olof had found.

“Fred Blakeley [leader of the CAGE expedition] nailed it when, years later, he labelled Lasseter ‘a liar and a fraud’,” Chris says.

“There’s one thing for sure: if by some incredible fluke somebody stumbles over a rich goldfield in Central Australia, the only thing you can be damn sure of is it wasn’t Lasseter’s Reef – we know that now.”

To chronicle his findings, Chris has created a compelling two-hour video production that he hopes will one day be turned into a tell-all documentary.

“Everyone I’ve sent it to agrees it finally dispels the Lasseter myth,” he says.

Despite the mounting evidence stacked up against the existence of Lasseter’s Reef, an ever-growing list of people, from serious prospectors to maverick fortune-hunters, continue to look for it.

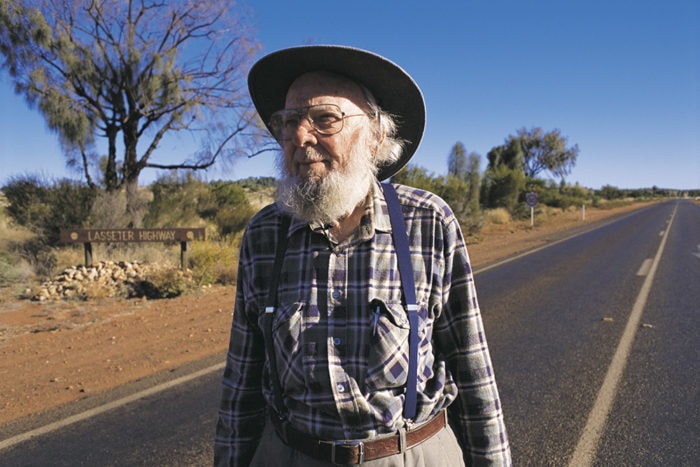

The most dedicated of these is Lasseter’s son, Bob, now aged 94.

Bob, who was just five years old when his father left on the ill-fated CAGE expedition, has spent much of his adult life trying to restore his father’s reputation.

He’s completed more than 30 separate expeditions, combing the deserts of Central Australia through often inhospitable country.

“My father wouldn’t have taken the risks he did if there was nothing in it,” he says in an interview in Lasseter’s Bones. “It is right for me to prove that my father was correct.”

Early in the documentary, Bob’s wife, Elsie, makes an on-screen plea to filmmaker Luke Walker.

“The newspaper accounts tend to take the mickey out of Bob because he’s going to look for the reef,” she says. “I sure hope yours comes through a lot nicer.”

Clearly operating under this constraint, Luke generously tiptoes around Lasseter’s nefarious nature. But others, such as Robert Ross, creator of the online encyclopaedia of information about Lasseter, Lasseteria, are much franker in their assessment of his character.

“Of course Lasseter’s Reef does not exist and never has; the whole thing is a litany of fake news and faker history,” Robert says.

“It is indeed an unbeautiful lie and the victim is going to be Bob Lasseter; he has believed, utterly and completely, a fraud perpetrated by his father and a whole lot of rogues that I wouldn’t have at my table.”

Anyone who’s visited ‘Lasseter Country’ will know Bob is far from alone in his quest to find the legendary reef – it’s almost become a rite of passage for anyone travelling through the Red Centre and beyond.

One such hopeful planning a trip to Lasseter Country this year is Jacob West. Now living in Bendigo, Victoria, Jacob grew up in the Northern Territory close to the route travelled by the fateful 1930 CAGE expedition.

“As a kid I always found the whole story fascinating,” says Jacob, who admits to well and truly falling victim to the Lasseter bug.

“I’ve collected every piece of Lasseter literature I can put my hands on, and can’t wait to get out there and search for the reef myself,” he says.

“It’s the sort of country that just really gets under your skin.”

One of the more popular destinations for those in search of the reef is the cave in the Petermann Ranges where Lasseter bunkered down during his last days in January 1931, waiting for help after his camels bolted with most of his provisions.

It was here that a starving Lasseter famously scrawled some of his last words in his diary: “What good a reef worth millions? I would give it all for a loaf of bread”.

Not surprisingly, given his extensive research, Chris Clark believes anyone looking for Lasseter’s reef is wasting their time.

“That tri-border area [SA, NT and WA] has been criss-crossed by so many expeditions, if there was anything even remotely resembling what Lasseter described, it would have been found by now,” he says.

In contrast, Dick Smith, ever the adventurer and also a good friend of Bob Lasseter, believes the quest to find the “Holy Grail” of outback Australia “should continue forever”.

“I want people to keep searching for it because it is the most wonderful Australian romantic mystery. It’s our El Dorado,” Dick says.

“And it’s very important for our country to have people like Harold Lasseter, who, for me, was an extraordinary adventurer who genuinely believed there was a reef out there and went out there to search for it and lost his life trying to find it.”

Despite his obvious enthusiasm, Dick confesses that “deep down” he hopes the reef is actually never found.

“I quite like the idea of it being out there but never able to be found because you can keep searching for it,” he says, recalling another outback mystery that he did solve: the location of the Kookaburra, the light aircraft that was forced to land in the Tanami Desert in 1929.

“After several unsuccessful attempts, in 1978 I made the mistake of finding it in the Tanami, and the problem in doing that was I couldn’t go searching anymore,” Dick explains.

Renowned for offering rewards for conclusive evidence of thought-to-be extinct species or for proof of so-called paranormal abilities such as water divining, Dick falls short of offering a financial incentive to anyone who finds Lasseter’s Reef.

“There’s no need to put out a reward for the reef, for if someone found it they’d be so immensely wealthy because it’d be worth millions of dollars,” he says.

Dick believes the reef could be found one day. “There’s more chance of Lasseter’s Reef being out there somewhere than the extinct Tassie tiger still being found alive,” he says.

Debunkers of the Lasseter’s Reef myth may disagree, arguing that at least there is proof the Tasmanian tiger did once exist.

This article was first published in Issue 150 of Australian Geographic. Purchase your copy here.