GALLERY: 30 years of AG photography

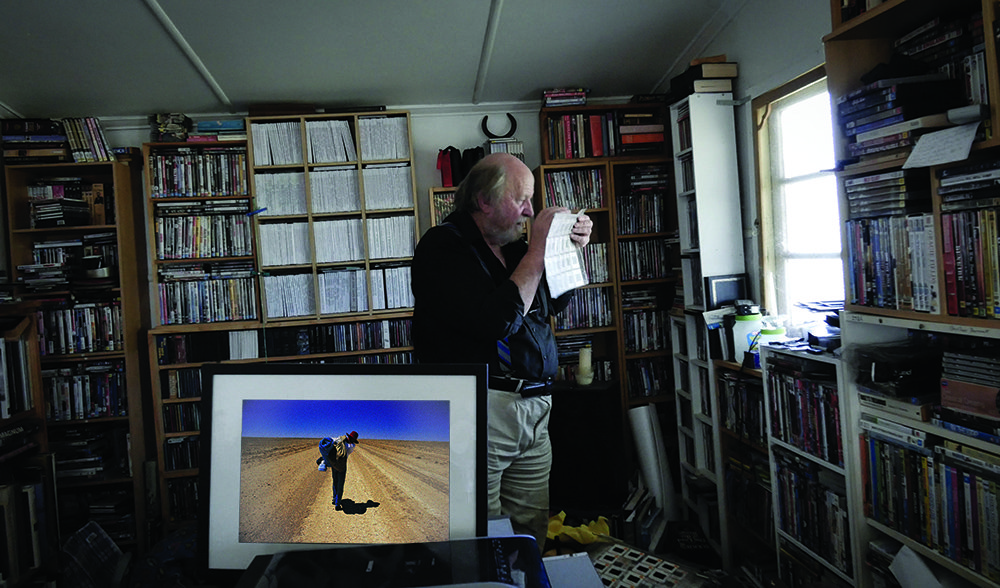

It was summer on the Birdsville Track and the temperature had soared to 52 Celsius. At Mungerannie station, near Marree in South Australia, there was a radio message waiting for writer Paul Mann and me from the police at Leigh Creek South – there was a man walking alone on the track. He’d packed up his swag and walked out of the cattle station that morning with only a litre of water. He was wearing a bright red felt hat which we easily spotted a couple of kilometres along in the flat desert landscape. Paul was driving and I asked him to pull up short and allow me to jump out. The man in the red hat looked back briefly and I signalled him to keep going as I took the photograph that was to become such a signature image for Australian Geographic for so many years.

The man was Graham Childs, a quiet, gentle stockman from a cattle station at Turkey Creek in the Kimberley. He’d walked and hitch-hiked down the Tanami and Birdsville tracks to visit his mother who lived in Cessnock, in the Hunter Valley. When I asked him how he enjoyed the visit he replied – “only stayed two days, couldn’t stand the big smoke.”

He camped with us that night and he showed us how to find wild yams and berries and elusive water soaks. He explained how he had learned to survive in the desert while living for three years with an Aboriginal community near Turkey Creek.

Photo Credit: Dean Saffron (Framed photo by Colin Beard)

Photography is often like a treasure hunt where a keen eye, patience and time in the field will bring the rewards. Exploring the tree-clad mountains in Tasmania for a feature on the Australian forestry industry with writer Ken Eastwood – and often in the company of big tree hunters like Brett Mifsud – you always had to be ready for the unexpected. Negotiating this country my eyes were focused on the ground hoping for a decent footing as much as they were looking up searching for massive trees. On the hunt for 400-year-old, 90m-tall giants, I walked kilometres, often negotiating steep ground and crossing swift streams. This photo is the kind of revealing shot that gave me a fulfilling sense of discovery. In this case it was a giant Eucalyptus regnans rising in the soft light from a carpet of tree ferns. I composed this photo in a matter of minutes, then headed off in search of the next treasure.

Photo Credit: Bill Hatcher

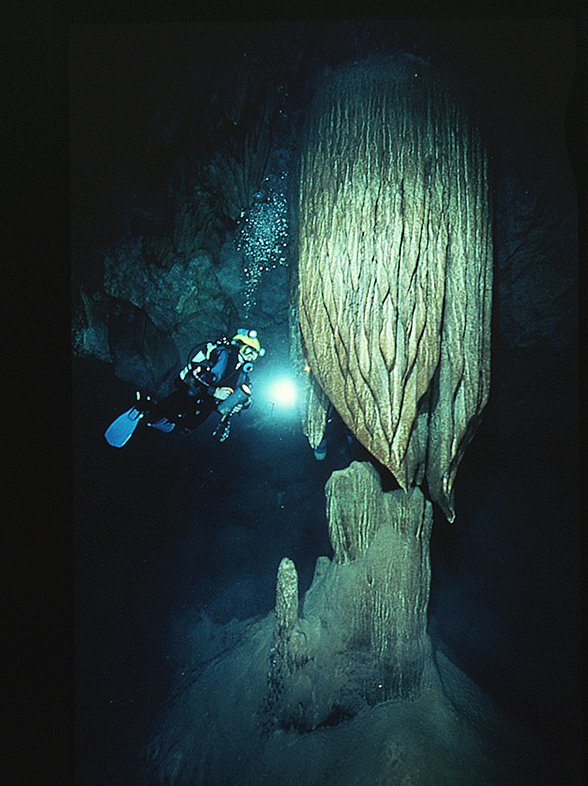

This image of Rapunzel’s Tresses (also known as The Shaving Brush), stands out in my memory for its documentary value. Sub-terrestrial flooded caves like McCavity in Wellington, NSW, are totally black, and these hidden realms had likely never been seen before by anyone. These caves are physically demanding to get into, require experience and special training to negotiate safely, and are hard to photograph successfully. Lyn Vincent models here with a light. Her husband Neil was holding a remote flash (strobe) behind the flowstone for added light. The photograph enabled a broader appreciation of the size and splendour of this calcite structure than it’s typically possible to achieve while diving. That’s why it’s so special. It reminds me of the huge time span of Earth’s geological history compared to our own lives, and it remained hidden from humans until relatively recent times.

Photo Credit: Mark Spencer

I was in Broome for a special assignment – the 82km Lurujarri Heritage Trail. I was waiting in the grounds of the old “native hospital” with fellow walkers and members of the Goolarabooloo community when writer Dallas Hewett called me over to meet Therese Row, sister of the late Paddy Row, whose vision made this cross-cultural experience possible. During an interview with Therese in her home in the old hospital building, she grabbed a picture frame containing four faded photographs and sat down heavily on the bed. She pointed her finger at a serious-looking young man and said “this one – he do a bad thing. He kill himself”. As she spoke I took the photograph. I barely remember pressing the shutter but I still remember, however, the deep resigned sorrow in her voice and the look in her eyes. This brief, intimate and very sad moment in her depressing home captured the plight of Aboriginal people for me in a single image: a daily struggle with depression and suicide, domestic violence and abuse, racism and poverty.

Photo Credit: Don Fuchs

The Boathouse, a colourful wooden building nestling beside the harbour in Currie, King Island’s main town, was featured in several photos in a story I shot in January 2009. Less than a week after I photographed it, it burned to the ground. Knowing it had been rebuilt and seeking a postscript to our 2009 story, I returned there in October 2015 to find a new structure almost indistinguishable from the original. Fortunately the building was insured and it rose again from the ashes, thanks to a big community effort. “I was absolutely staggered at the way everyone came together to rebuild the boathouse,” says local Caroline Kininmonth. “Its loss devastated the locals – everyone felt the soul of the island had been taken away.”

Now known as “the restaurant with no food”, it’s stocked with all the tools needed for everything from a picnic to a dinner party. Locals and visitors alike are welcome to use it any time on a BYO-tucker basis, with an honesty box for donations to the building’s upkeep.

Photo: Sitting on the upturned boat are (L-R) commercial fisherman Paul Jordan, kitesurfer/fisherman Ben Hassing, artist Robin Eades and Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife head ranger Shelley Graham (with baby on lap). Among others who turned up for Bill Bachman’s return in October 2015 are King Island Dairy head cheesemaker Ueli Berger and artist/tourist operator/berry farmer Caroline Kininmonth. Standing at left behind boat in the green short–sleeved shirt is cattle farmer Fred Perry among other King Islanders.

One of the things that I truly regret, and am quite ashamed of, is not learning any Aboriginal languages despite living in the NT for nearly 30 years. I know a smattering of Yolngu Matha, the language from north-east Arnhem Land and similarly Bininj Kunwok, from western Arnhem Land, but I really ought to be able to converse with the many indigenous people I meet through my work. When I hear the lyrical sounds of Aboriginal people talking – no matter where I am in Australia – I am taken with the beauty of their language. Frequently, their words go deeper and mean more than our own technical and commerce-oriented language. I photographed these women in the dry bed of the Hanson River, near Ti Tree in central Australia. They were Anmatyerre and Warlpiri speakers and were working with non-indigenous linguists to revive and strengthen their languages so future generations can understand and speak them. Like the flora and fauna of Australia, many indigenous languages have become extinct and we’re all the worse off for it. Those who have made the effort to learn one or more indigenous languages, see this country in a way the rest of us never will.

Photo Credit: David Hancock

I was working with herpetologist Arthur White on a feature about the endangered green and gold bell frog. I wanted to make the frog look heroic while making man look like the predator. The story was about how frogs were indicators of clean and healthy environments and how their habitats were disappearing due to contamination by humans. I put a soft box on the flash inside an enclosure and lit the frog within with really nice soft light to bring out its beautiful colours. In the background, I lit Arthur with a harsh flash that made him look menacing. The narrow focus makes the frog sharp and Arthur blurry and unrecognisable, so he could be viewed as a symbol of the human threat. The shot became the opener for the feature. Another shot from this assignment was selected for the cover of the Twenty Five Years of AG Photography book in 2010, and I’m incredibly proud of that.

Photo Credit: Mike Langford

It was with a mixture of trepidation and curiosity that I was welcomed aboard the Diana, a deep-sea trawler, by her crew, to head out into the Bass Strait on an assignment. I felt like a Hemingway character following schools of fish and fixated on the hunt. Conditions in the open ocean were so varied. One moment it’s a vast glassy lake teaming with birds gliding the thermals and within hours 10m waves are threatening to engulf us. This contrast is probably why this is my favourite AG shoot. One day the crew finished work and indulged in a bit of thrill seeking. Wearing raincoats, they would stand on the bow while the ship heaved through the heavy swell. I was high on the observation deck when suddenly a huge wave enveloped the lads. I was looking through the lens as the wave also broke over me, completely ruining my lens. I was lucky to save the memory card and this image. I have immense respect for the fishing crews labouring at the mercy of the elements. This was truly one of my great adventures. It’s not easy being on a small vessel, with five other guys, for weeks at a time out in a massive and dangerous sea. It teaches you about yourself, reliance on others, the division of roles, hunting and foraging and the link between all of these and the natural world.

Photo Credit: Dean Saffron

It was my first job for AG; a story about the people that drive the nation’s huge roadtrains. We’d arrived at the Hay Plain in NSW at dawn. The landscape was as featureless and flat as the road ahead. The best way to capture the enormity of the place would be from above; I only had the truck we were travelling in to stand on. I climbed on the roof of the cab barefoot – it was highly polished and slippery. I had a look from up there but it was too still and quiet. I needed movement to truly capture the endless transit of a trucker’s life. I asked the driver to get on the road and drive at normal speed. I had my back against the trailer, and my feet glued to the shiny surface of the cab’s roof like a gecko’s feet to a window. It felt like being on the bow of the Titanic. Then the sun broke the horizon. To get the truck’s bright paintwork and fittings in the foreground, I used the widest lens I had, a 30-year-old, 18mm manual lens I picked up at a garage sale for $20. The greatest bonus of all was that the shot was not only used to open the story. From a technical viewpoint this is just a snapshot; there’s no lighting technique and the composition couldn’t be simpler. Yet it’s my most memorable for the magazine.

Photo Credit: Thomas Wielecki

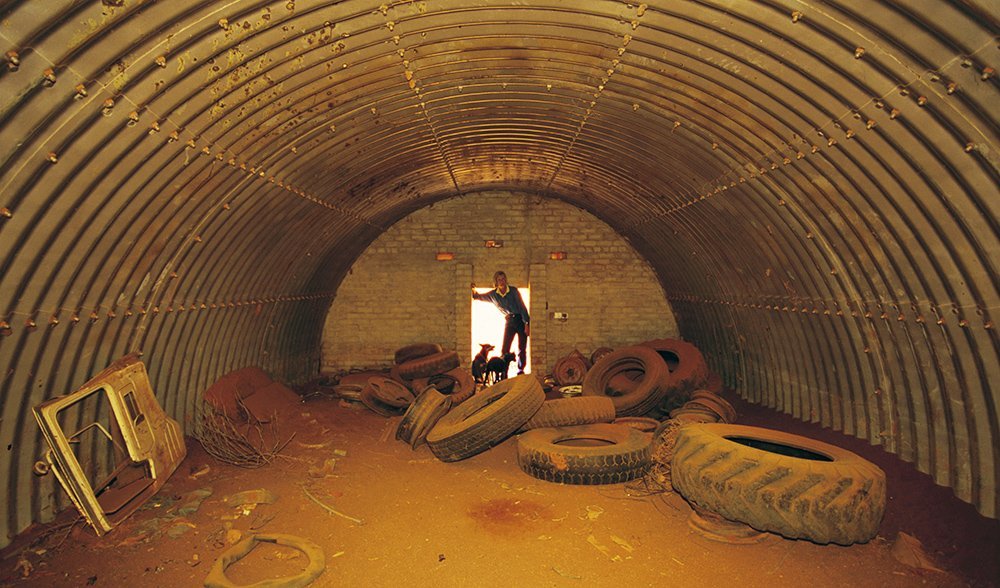

Sheep farmers, Japanese rocket engineers, gold miners and scientific boffins made this assignment in the Woomera Protected Area of SA so particularly memorable. The people I met through my viewfinder were as diverse as the landscapes writer Ken Eastwood and I traversed. I was shooting with high-end digital already by then, so I was rather surprised when AG insisted I shoot film. I’d not worked with it for four years. Can you imagine these days, shooting in excess of 80 rolls of film and not seeing the results until they hit the lightbox! We travelled with a Geiger counter to check radioactivity levels, and it sometimes gave us good reason not to hang around, as the needle occasionally went off the scale.

A cup of tea with workers on the nation’s second largest sheep station, Commonwealth Hill, was followed by safety training that gave us accredited survival skills for a 1.2km journey underground into the Challenger Gold Mine. Hundreds of such bunkers like the one pictured here were built for the safety of pastoralists in the Woomera Protected Area in the 1950s. We learnt that upon the announcement of a rocket launch, in true Aussie spirit, rather than dashing inside the bunkers for safety, locals would line up deck chairs and eskies on the roofs for a good view of the coming light show.

Barry Skipsey composed and performed a song to help celebrate the magazine’s 30 birthday in 2016. Listen here.

Photo Credit: Barry Skipsey

How can anyone be charmed by a cane toad? I can. That’s because cane toads are Queenslanders and I’ve always had a soft spot for them. When I came to Australia 30 years ago, I set off with my husband on an archaeological expedition to outback Queensland. For a greenhorn from Los Angeles, this land of true adventure was a culture shock.

During the cane toad assignment for AG many years later, I recalled those first adventures. Even though I was now studying toads, not ancient artefacts, the people there still represented those uniquely Aussie values that I had come to admire so much: doggedness, laissez-faire, irreverence, a wry humour, and coping against the odds. Of the many assignments I’ve done for AG, I voted for this pic as my favourite because the cane toad job moved me the most.

Photography is about the moment, and though I strive for beauty and design, it’s emotion that’s primary. That assignment was my first opportunity to rediscover what I loved about Australia. I only planned to stay three years. Why did I keep postponing my return “home” to California? I finally realised I was charmed by the people, specifically those sporting my favourite value, which is so well represented by outback Queenslanders. Sure they have loyalty and all the other good stuff, but always there’s irreverence. Let’s not take anything too serious, mate. And yet somehow, despite the words and jokes, and no matter how tough, the job always gets done. But will they ever get rid of the cane toad?

Photo Credit: Esther Beaton

When AG asked me to shoot a story on the alternative lifestylers of Nimbin, I didn’t think it was a good idea given a tropical cyclone was blowing off the WA coast that I knew would bring heavy rain across the continent. I requested a 4WD but the car hire company at Ballina only had a little red Ford Laser. I attended a meeting with one of the communes to obtain their cooperation. The men were quite defensive but the women were easier to deal with. I assured them that they wouldn’t feel like fish in a fish tank and that I’d explore how all the communities were working alongside each other, from the older generation farmers to the newer alternate ones that were established after the 1973 Aquarius Festival. As the meeting finished, the thunderclouds moved in and I didn’t see the sun for the next week and a half.

I spent a lot of time pushing the little red car out of mud or driving across country creeks and flooded roads, hoping not to get swept away. Sometimes I just abandoned it and hiked cross country with my heavy camera pack on my back. The assignment had all the ingredients of a true adventure. I got around and visited lots of communities.

I photographed Dooy Holmes and baby Jemima in poor light during a short break in the weather. I asked AG for extra time to wait for better weather but they needed the photos quickly. When I tried to leave, I couldn’t, I was stranded and couldn’t even reach the town of Nimbin. I had to organise a helicopter to get me to Coolangatta Airport as I had another big assignment waiting back in Sydney. The flight was pretty rough, even the co-pilot was airsick. Me and my cameras were subjected to extreme conditions and I was worried about what I had shot, but when I finally saw this photo, I knew I had a winner.

Photo Credit: Peter Aitchison

I was excited to shoot a story on Purnululu in the Kimberley in 2006 because it was, and remains, one of my favourite places. The beehive shapes are, of course, spectacular, but from a photography point of view they can be difficult to arrange into a balanced composition. I spent quite a bit of time exploring various viewpoints, looking for a scene that captured a sense of place and could stand alone as a ‘hero’ shot. Once I found this vantage point just to the south of Piccaninny Creek I knew I had a strong image, so I returned in the pre-dawn light and was delighted when the resulting shot was selected to be one of the journal’s earliest photographic covers.

Photo Credit: Nick Rains

Home History & Culture GALLERY: 30 years of AG photography