Camel mounties: the largest beat on Earth

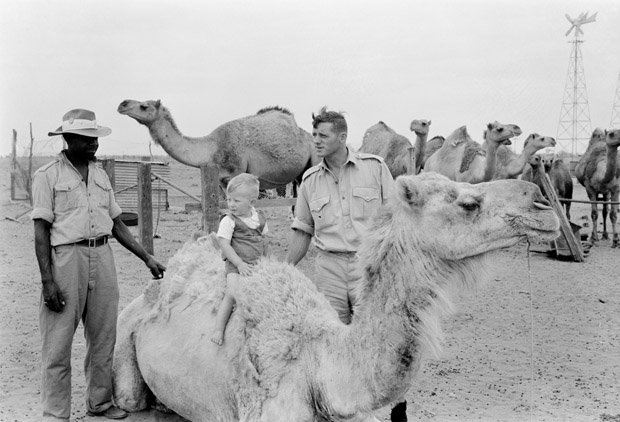

AS RON ‘BROWNIE’ BROWN, mounted on his grey camel Pearl, swayed across the gibber plain in the sweltering heat of the desert, this sort of police patrol was already on the way out. It was 1951 and the roar of Land Rovers was heralding the swansong of both horses and cantankerous camels, which were then the key mode of transport in close to half of the Northern Territory’s police districts.

Wartime lessons learnt in the Middle East, such as slightly deflating the vehicles’ tyres, and the construction of the Lasseter Highway made motorised patrols more reliable. And the extra duties of wildlife control, stock inspection and community welfare once handled by the one or two policemen based in the Finke Police District were also being divvied up between government officials.

First used for patrol duties by the SA police in 1881, the policing role of camels expanded in the ’40s amid calls for greater defence of the north-west, but Central Australia’s Finke Police District was still reputedly the world’s largest beat. Spanning the remote space between Mount Dare station, Alice Springs and Mt Gosse in WA – passing Kata Tjuta (the Olgas), Uluru/Ayers Rock and Lake Amadeus – it dipped over the border into SA, where officers acted as Special Constables.

A historic outback icon

The camels were a practical choice to traverse the vast Red Centre, if not always a comfortable one. Contrary to popular belief, a camel’s hump is not full of water; it is filled with fatty tissue that retains fluid, shrinking if the animal is unable to drink. This hardy feature earned camels the moniker ‘ships of the desert’.

After one 11-day stretch without water, the camels’ humps dwindled away to mere bumps. For the most part, the patrols – which could take four months, and used up to six or seven camels strung one behind the other by ‘nose-peg lines’ – served an important symbolic purpose. News of misdeeds would travel down the mulga wire, but the tough conditions and isolation produced folk who were often a law unto themselves.

Police and camel visits were a reminder of the presence of the law. “Much the same effect, I assume, that it has on us today when we see a police car going along the road,” said Brownie (who died in 1994) during a 1979 NT Archives interview.

A rare point of contact, officers wore almost every official hat that existed in their 203,107 sq. km bailiwick. Brownie’s titles included: Inspector of Stock; Registrar of Vehicles, Marriages, Births and Deaths; Protector of Aboriginies; Warden of Mines; Protector of Birds and Collector of Public Monies.

The last camel patrol

Over the years history has become muddied as is often the way with old bush tales. “It would take someone combing through the old police journals to untangle it,” says NT archivist Pat Jackson.

Anthony ‘Ned’ Kelly tells one version of the last camel patrol. It was May 1953, and involved the pursuit of Aboriginal man Barry Mutarrubi, a suspect in the murder of an Aboriginal woman. Barry had retreated into the desert near Curtin Springs station. Using five camels, Ned, patrol officer Les Penhall and an Aboriginal tracker known as Stanley chased Barry until he disappeared over the WA border. Stanley and Ned caught up to Barry months later when he returned to the NT. He was tried in Darwin and served time in jail for the murder.

“The end of the camel patrols did not end the isolation of the Centre,” says historian Bill Wilson, a former Charles Darwin University lecturer who specialised in the NT police force’s exploits. “But the story of the Australian camel ‘mounties’ captured the romanticism of the outback for people all over the world.”

Today, Dr Robin Gregory of the NT Office of Environment and Heritage is working on having the Finke Police Station listed to preserve what was once the hub of the largest beat on Earth.

Source: Australian Geographic, Issue 99 (Jul-Sep, 2010)

RELATED STORIES