Unzipping deep blue genes

A disproportionate number of marine genetic sequences – primarily from microbes, fish and coral – have been prospected and patented for product development by multinational corporations when compared to those from universities and national or government agencies, according to a recent study.

The 2024 study from Nature Sustainability scoured genetic and patent databases to determine who were the primary users of marine genetic resources in their research, which species were listed in these patent filings and to what extent data sharing was transparent.

Of the 3636 unique patents analysed, 1675 were owing to multinational corporations, primarily headquartered in the USA, Germany and Japan. This monopolisation of shared marine resources to a few private organisations within a few nations has since sparked fierce debate about the equity of science versus corporate interests.

Top 100 largest patent applicants in marine bioprospecting, aggregated by applicant type. Source: Growing prominence of deep-sea life in marine bioprospecting, Jean-Baptiste Jouffray, Paul Dunshirn, Agnes Pranindita & Robert Blasiak

But why and how are private entities patenting the inner materials of underwater life? How ethical and sustainable are these practices? And how does this affect our national and Indigenous interests?

Treasures beneath the waves

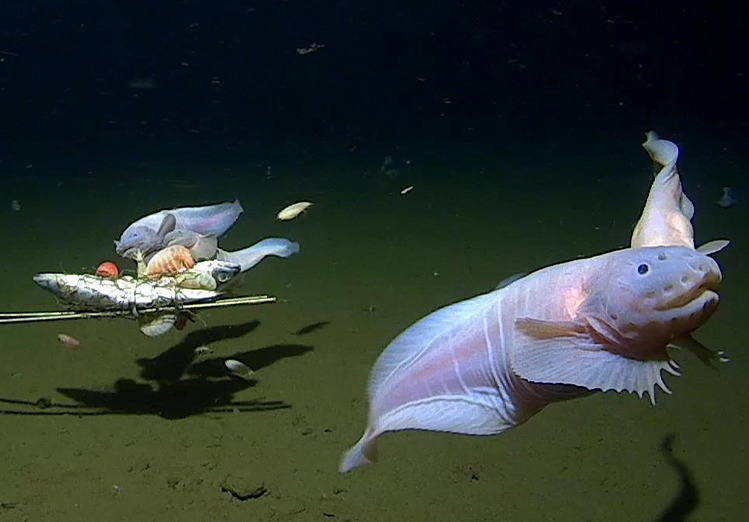

While the extraction of naturally-occurring compounds is nothing novel (feel free to look at the sources of most food additives, over-the-counter medications or the history of Eastern medicine), a new era of marine biodiscovery has been propelled by the vastness of our unexplored depths (only 26 per cent of the oceans have been mapped). The gaps in our knowledge about new and undiscovered marine life remain vast (now over 240,000 described species), yet we’re finding marine-derived compounds are on average two to four times more efficient than their terrestrial counterparts.

Amongst the novelties acquired from international underwater expeditions are bacteria that can break down plastic pollution, green luminescent molecules from jellyfish and anti-cancer drugs from the defensive secretions of sea sponges.

These products have since been published and commercialised to much critical acclaim, with the jellyfish green fluorescent protein winning the 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry as well as contributing greatly to the USD $2.4 billion fluorescent protein market.

Early 21st century Australian research sought to recapitulate this academic and commercial prosperity with several independent forays into herbicides, sunscreens and painkillers from Great Barrier Reef organisms.

Though met with limited success, these works highlighted the high proportions of native marine biodiversity yet unexplored for proprietary compounds (roughly 10–13 per cent of global biodiversity), even triggering a parliamentary inquiry into industrial and academic funding for bioprospecting.

National progress since then has been slow, but this is partially due to a revolution in the way products are sourced: advances in the cost and accessibility of genetic sequencing, openly accessible genetic databases and the ability to manufacture biological materials from scratch have allowed international corporations to acquire patents of publicly accessible genetic sequences from biodiversity research and produce them in-house.

For some, this could seem ethically dubious as it constitutes an intellectual property claim to something living.

As it turns out, the complexity of genetic patenting law, discrepancies in political regulation between nations and in international waters, and the relatively slow pace of the law relative to biotechnological innovation have allowed for multinational companies to capitalise amid the turmoil.

Patenting of life’s sovereignty

Emeritus Professor Dianne Nicol holds a long and successful career at the forefront of genetic patenting, serving as the previous director of the Centre for Law and Genetics at the University of Tasmania. Citing several major court cases both nationally and internationally, her reactions to the Nature article findings are primarily of disbelief.

“It doesn’t matter if it’s human or a microorganism or an animal or a plant, just taking a gene sequence from its natural environment and not changing the informational content is not enough to say you’ve got something that crosses the inventive threshold,” she says.

Professor Nicol speaks primarily from the perspective of the United States and Australian governments, which due to landmark cases in 2013 and 2015 respectively, ruled that isolated genetic materials without modification cannot be patented.

Knowing these timelines, we can look through the database from the 2024 paper to see there are still tens of thousands of patented sequences filed after 2013 to the World Intellectual Property Organisation, based in the US.

These sequences claim to be from areas beyond national jurisdiction (or international waters) and therefore not subject to national regulation, but the concern is that around 63 per cent contain no species or geographic information, data necessary to verify the legality of the acquisition.

Furthermore, since the ecological range (the habitat) of some species can be in a state of constant flux, spanning thousands of kilometres depending on migratory capabilities, this obscures whether they reside exclusively within international waters.

“It’s a complex area, scientifically, legally, policy – you name it. You have to be across all these things. It’s really tricky.”

Muddy waters

Professor Charles Lawson at Queensland’s Griffith University is another of the few whose expertise spans these topics, boasting a career in both public and private litigation surrounding genetic patenting and biodiversity. He offers intimate knowledge of the loopholes that can be taken advantage of.

“Yes, [sequences] can be patented in Australia, but you need to be clever about how you do it,” he explains.

Professor Lawson states that previous rulings have held much ambiguity surrounding whether DNA is a chemical or information, and there are different bodies governing seabed resources depending on whether they are living or material resources.

“If I were to get marine bacteria from the high seas and extract sulphur, am I extracting a mineral resource or am I dealing with a living resource?

“The overlap between what is a living marine resource and what is a mineral resource is not entirely clear…It depends how you want to frame it.”

While an expert on the litigation of marine resources, Professor Lawson maintains the opinion that too much time and resources spent on regulation of these dubious practices may hold up otherwise beneficial scientific discovery for marine biodiversity.

“Even if we have 10 new billion-dollar pharmaceutical products every year [from marine sequences], that comes nowhere close to biodiversity funding and nowhere close to the Sustainable Development Goals [from the United Nations].

“We’re tying up scientists and spending valuable research dollars on incredibly complicated regulatory systems when the outcomes of what they’re going to fund are trivial.”

Though regulation and policy may be up for debate, what is prioritised by both the paper and Professor Lawson is the assurance that monetary or otherwise benefits are shared to Indigenous and cultural stewards.

“Our focus needs to be on…the broader public and social benefits from the outcomes of science for the less developed countries and Indigenous peoples,” he says.

Any genetic resources leaving a country are under the Nagoya Protocol, an international agreement which regulates both the access to genetic materials and the sharing of monetary or other benefits to native and cultural stewards.

While Australia is not a member, the federal Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water maintains that existing practices are in line with this.

Dr Fran Humphries, a colleague of Professor Lawson at Griffith University, is a delegate for the High Seas Treaty; an international protocol regarding the management of marine genetic resources in areas beyond national jurisdiction.

She notes the substantial amount of work already underway, referencing a soon-to-be complete guide to the interpretation and implementation of the treaty. Prominent topics include benefit-sharing and regulation of sustainable and ethical practices.

The long trawl

Whilst a potential monopolisation of marine sequences could be cause for concern, Professor Nicol emphasises that there is always a lag between scientific discovery and regulation, she notes an often-used adage about science and the law:

“The law is always at the back, limping a little bit.”

Limp as it may, the independent enquiries into these practices from leading scientific institutions, lawmakers and legal academics provide assurance that this issue is taking precedence in a variety of settings.

It will, however, remain to be seen how national policies seek to define the nature of DNA, how national policies on genetic sequences are translated to international waters, and how international law will regulate both their ethical acquisition and monopolisation.

Until then, one can’t help but wonder which creature comforts we’ll end up owing to our great oceans.