Awakening a sleeping language

Members of Aboriginal communities are warned that this story may contain images and names of deceased people.

Thomas Watson had an “awesome childhood” growing up in Katherine, in the Northern Territory, but being away from his ancestral home in Queensland, he always longed to connect with his family’s culture. “I always knew I was Aboriginal and have been proud of it, but there was missing knowledge and a hole that I felt I needed to fill.”

Born in Melbourne, Thomas spent most of his childhood in the NT because his grandmother moved there in her twenties.

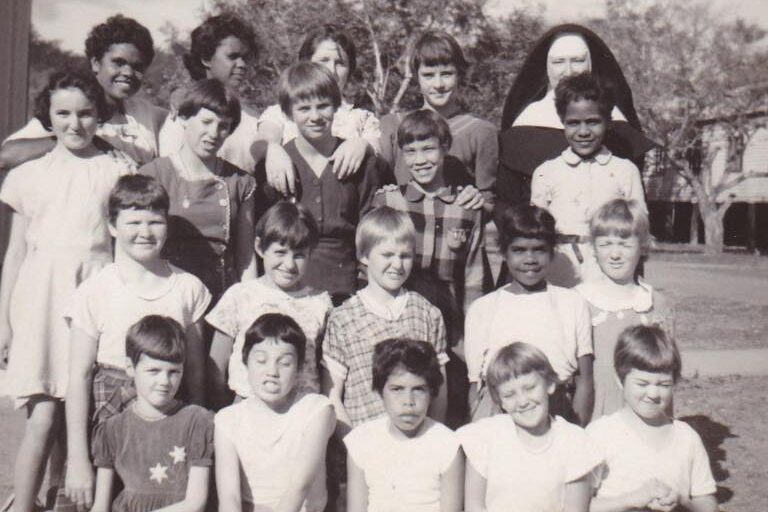

“At two-and-a-half-months old, my grandmother and her twin sister were moved to St Joseph’s Home, Neerkol, because their mother was unable to support them. Their mother was a domestic servant, and their father was a stockman, so they were incredibly poor. They were able to see their parents on occasion, but my grandmother has very little memory of her mother, which is really sad,” Thomas said.

“Because of all the policies, restrictions and general treatment of Aboriginal people and our culture and languages at that time, my nan was never taught anything about our culture, and therefore neither were we. My grandmother couldn’t even remember the name of our mobs.”

It wasn’t until he started university that Thomas caught a proper glimpse of his ancestry.

At the start of his Bachelor of Health Science and Bachelor of Applied Science (Osteopathy) at RMIT University, Thomas participated in Gama-dji, an orientation week for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students. He took a seat at random, and during an icebreaker activity, the students started talking about their families. Thomas met someone whose last name was White – his grandmother’s maiden name.

“We found out that her great-grandfather is my great-grandfather’s brother,” Thomas said. “And so that is how I discovered that my family is Gangulu. I finally had a mob that I could say I belonged to, which was very special. I had a bit of a cry over that.”

Armed with this new information, Thomas – then 21 years old – prepared for a family reunion, purchasing a GoPro and a notebook to record everything he could learn about his culture when he returned to Country. However, upon arrival, Thomas discovered he couldn’t learn his language as nobody spoke it anymore.

“That experience lit the fire in my belly because I didn’t want to accept that my language wasn’t there anymore,” Thomas said. “I was so excited to learn it, and then it no longer being there didn’t sit right with me.”

Rediscovering what was once lost

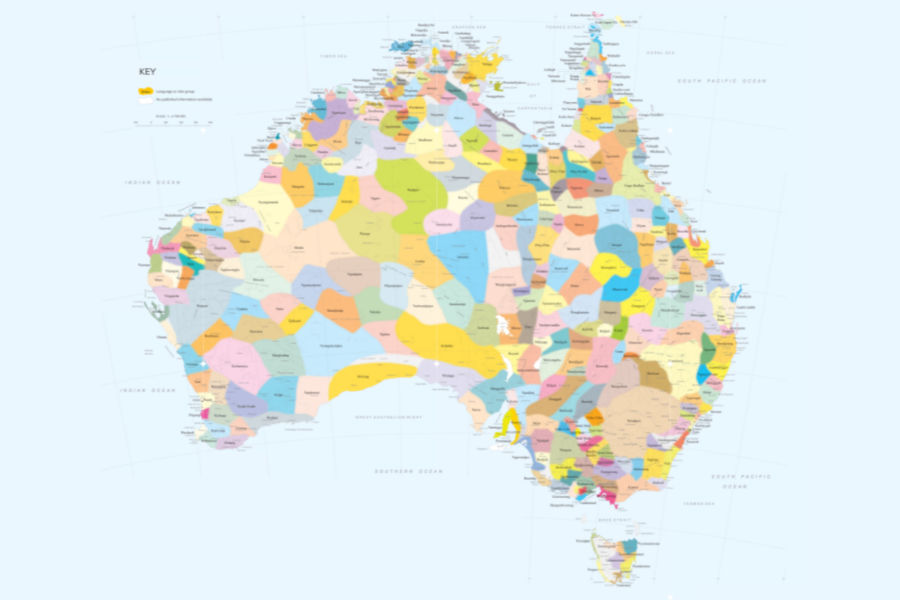

At the time of European colonisation, about 250 distinct First Nations languages were spoken across Australia. Approximately 150 languages are still actively spoken, with only 14 considered strong. Around 110 languages are considered severely or critically endangered, according to the National Indigenous Australians Agency.

Languages that no longer have native speakers – that is, no one who learned it as a child – are often described as being “extinct”. Thomas, however, prefers the term “sleeping language”, which has an important distinction – a sleeping language can be reawakened.

Refusing to give up on his language, Thomas started his research where every young adult does – with a Google search on his phone.

“I started by searching for the name of my mob on the internet,” Thomas said. “I clicked on every link and tried to work my way through the menus of all these different websites and resources until I came across a word list or a book.

“Initially, I was trying to find anything, but as I began learning more, I could search for more specific things.”

Throughout his investigation, Thomas repeatedly came across references to the book Linguistic Survey of South-Eastern Queensland. It was written by a Swedish linguist named Nils Holmer, who conducted fieldwork on languages from Queensland, northern New South Wales and the Torres Strait during the 1960s–70s.

Many other linguists critiqued Holmer’s publication, believing it did not provide sufficient evidence to support his observations. “They were effectively saying that they didn’t trust his publication, but this could be solved with the original notes, or what they call a ‘corpus’,” Thomas said. “So, that got me thinking, ‘Where is this guy’s corpus?’”

At this time, Thomas was working with linguist Andrew Tanner from Living Languages, an organisation supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in their efforts to preserve and grow their languages. The pair would meet each week to do language revitalisation work, their efforts now set on finding Holmer’s corpus.

One day, while researching, the pair emailed Claire Bowern, an Australian linguist currently working at Yale Linguistics, who knows Nils Holmer’s son, Arthur, a linguistics professor at Lund University in Sweden.

“They had a conversation 20 years ago, and she recalled that he said he had a collection of his father’s work sitting in his attic, but he’d never looked at it before. We thought that maybe if he had all this stuff he had never looked at, the corpus we were after could be there.”

The only problem was this collection was halfway around the world. Thomas and Andrew contacted Arthur and asked if he knew anything about the corpus they sought.

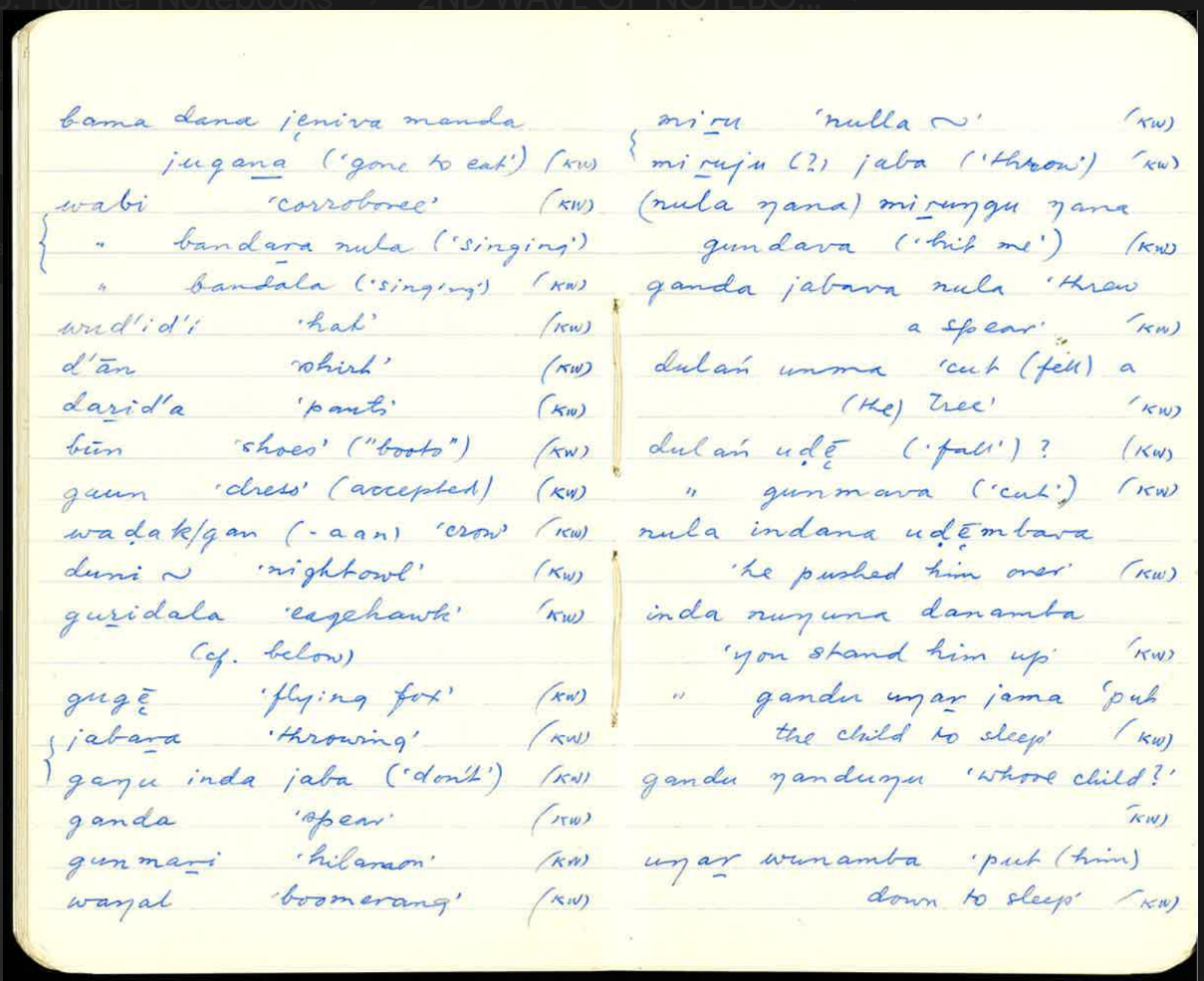

Initially, Arthur said no, but after a week, Thomas received an email with 12 scanned notebooks of Holmer’s original works. A week later, 14 more notebooks and six audio tapes appeared in Thomas’ inbox.

“Each of the 26 manuscripts – the field notebooks – are handwritten, and they contain languages from northern New South Wales, all of Queensland and up to Torres Strait,” Thomas said. “Seven of them were significant to me and my work in my language.”

Each notebook had around 160 handwritten pages on First Nations languages, meaning Thomas now had around 2660 pages worth of content to sift through.

Putting the pieces together

Thomas shifted from his career as a health professional and applied to become an Industry Fellow for Indigenous Language at the University of Melbourne, where he currently works part time on a grant for his language studies.

He is working for a platform called Nyingarn, an online database that makes manuscript sources of Australian Indigenous languages available as searchable and reusable text documents to support language revitalisation.

Thomas transcribed all seven Holmer notebooks about the Gangulu language.

“Now, using all the information I have collected over the years, me and a small team are writing the first Gangulu dictionary and learners guide,” Thomas said. “My greater goal is to bring back Gangulu, my language, and I want to speak it fluently.”

The awakened language will inevitably differ slightly from the original one, as Thomas and his team make judgements to the best of their knowledge and take inspiration from other local languages that are part of the same language family as Gangulu.

Because the language stopped being spoken around the 1970s, some words must be ‘invented’ to fill the dictionary with modern phrases. The primary ways of introducing new words to the dictionary is by adapting English words using the Gangulu phonetic system, or using the same process that other languages in Australia use to make words in their own languages that don’t draw any inspiration from English.

“A common one we already use is the word for car,” Thomas said. We say ‘murraga’, which is a phonetic take on ‘motor car’. When said in a sentence, you hardly even realise that it is technically an English word.”

Another word Thomas and his team have created is ‘dibi’ which means television, and is a phonetic play on ‘TV’.

Speaking to the future

Having his language back is extraordinarily special for Thomas, and he hopes that when he has finished the key work on Gangulu, he can start looking into other sleeping languages documented in Nils Holmer’s further 19 notebooks.

“Once this learners’ guide dictionary is complete, we’ll move straight onto making a new, updated version because we’re still coming across and trying to figure out the language as we go,” Thomas said. “Then, when we bring back Gangulu, we can use that to revive other languages from around us.

“When you start to come across language materials and word lists, you realise all the puzzle pieces are here. We just need to put them back together again.”

Thomas also emphasises the need for the current generation to take the initiative to learn about their Indigenous culture before it is too late.

“We are at a critical point where we must be passionate about and willing to uncover this stuff because otherwise when our Elders pass away, that knowledge will be gone forever.”

There is much hope for reawakening sleeping First Nations languages, and Thomas has proven that it is possible.

“I can now string together sentences off the top of my head, and although my grandmother can’t speak the language and doesn’t necessarily understand what I’m saying, I can see that she’s so excited when I talk to her in our language.

“It will take a little while, probably a couple of generations, but hopefully, by the time I have grandkids, they will be speaking Gangulu, too.”