Donkeys sweat. Snow’s coat is in a lather after the 7.5km walk through bush from Kalunga in far north Queensland to our campsite beside Cassowary Creek, off the unsealed Silver Valley Road. I stroke his muscular neck and tether him to a tree with a bowline knot I’ve only just learned to tie, and hope it holds. It’s sunset on day one of the week-long Packers’ Ghost Trek through rugged hinterland 75km south-west of Cairns. With us are eight other donkeys, and Tim Daniel, our guide, who served in the army for 42 years and for three of those ran a survival school. He’s in a work shirt, canvas trousers, and a fly-fishing vest labelled with everything he might need at a moment’s notice, from batteries to crepe bandages.

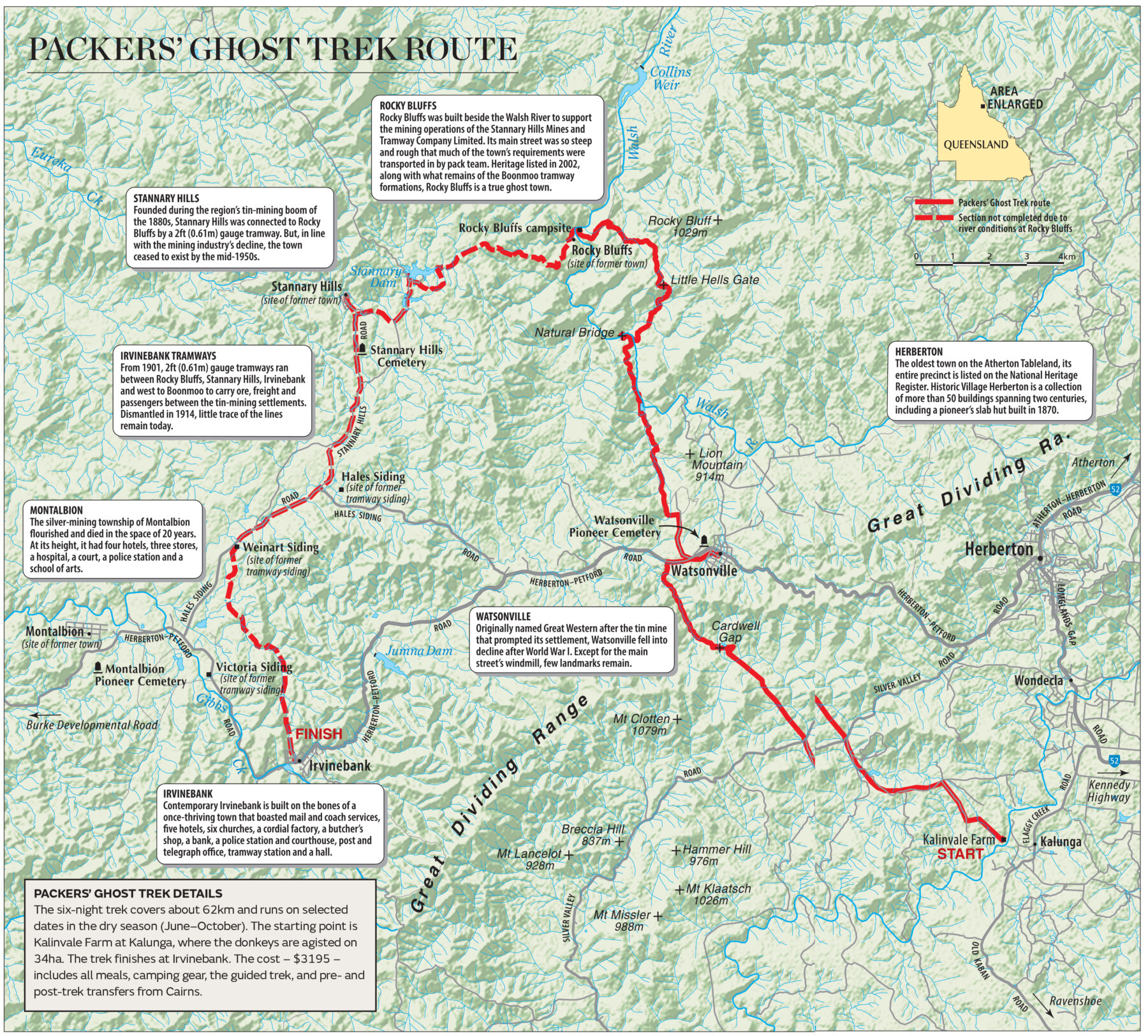

From his home in heritage-listed Herberton, Tim designed the trek to trace the footsteps of the packers and drivers of the thousands of horses and mules that traversed this region between 1872 and the turn of the 20th century. Transporting metals from the area’s emerging mines, along with settlers’ provisions and other goods, the packers and their beasts showed a determination as tough as the terrain. “This is how Australia travelled before the motor car,” Tim says.

Our route will take in some long-abandoned ghost towns, which once played a huge role in the state’s wealth creation. “This area was extremely rich, and probably provided much of the financial requirements for Queensland’s development at the turn of the century,” Tim says. En route we’ll pitch our tents at some stunning campsites only accessible on foot.

After a three-course meal cooked over a fire, I slouch back to my tent. Tim has the donkeys on nightlines, allowing them to graze. By my head torch’s light, Snow glows like an apparition. I slip into my sleeping bag, as another donkey, Duffy, fusses. “Just wait,” Tim tells the restless animal. “I’ll bring you a peppermint in a minute.” It’s the last thing I hear until morning.

Next day, we eat breakfast by the creek, sipping billy tea that tastes of campfire smoke. Duffy paws the ground, eager to get going. Donkeys can carry 22 per cent of their body weight, but loading their pack saddles takes time. Each side must balance to within half a kilo. “And if you don’t put [the pack] on right, it will fall off during the day,” Tim says.

Today’s 12km route is through tin-mining territory. Gold strikes at the Palmer River and Hodgkinson Goldfields, further north, attracted fossickers seeking their fortunes. But as deposits dwindled, or failed to live up to expectations, hopes turned to tin, lead and copper. The 1879 discovery of the Great Northern tin lode at Herberton was the first of several to bring settlers to the once-thriving towns we’ll visit – including Watsonville, Rocky Bluffs and Irvinebank. We cut through Cardwell Gap, the lowest point on this stretch of the Great Dividing Range, and onto Gorge Creek, where the grass is littered with paper daisies.

Two miners were speared here by the area’s original inhabitants in 1881. Both survived. Not so fortunate was “German Harry” (Hans Martens) whose body, minus a leg, was found 12 days after he disappeared from camp. His grave lies near here, but its precise location has been lost.

We’re treading a narrow pathway beside the creek when, suddenly, there’s a shout. The 240kg Snow takes off up the path, saddlebags shuddering. Next, there’s thundering hooves as three other donkeys, also loose, tear up the hill on the other side of the creek. More shouts. Some cursing. More running. As Tim scrambles to head them off, the trekkers catch and secure the others and piece together what’s just happened. Something spooked Milo, panic spread, and the donkeys knocked four trekkers off their feet. One woman hit her head; another has hurt an ankle. The latter falls a few more times, even after the group reassembles to continue the slower journey onward. It’s the first time anything like this has happened in the 20 years Tim has been leading treks.

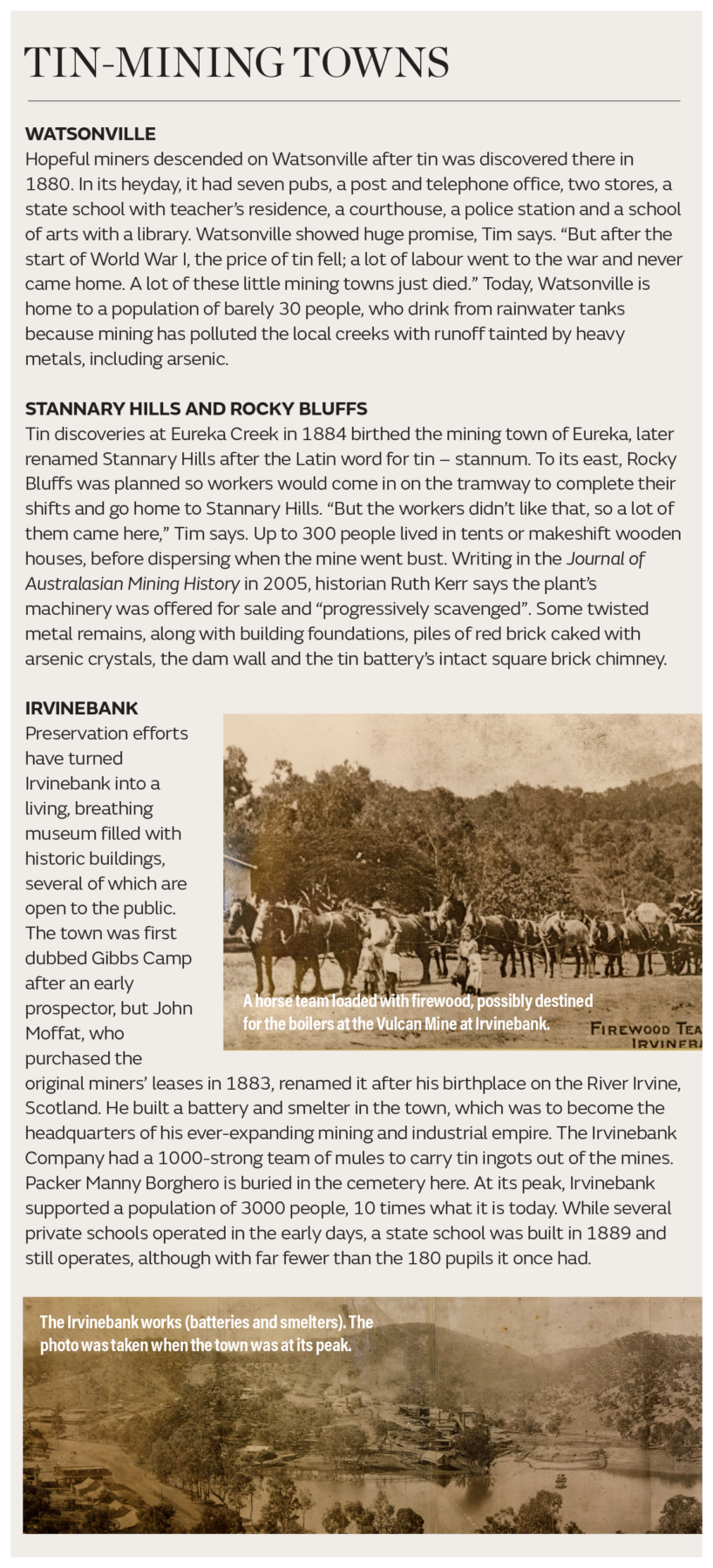

I wonder how packers managed larger, more powerful mules – offspring of donkey stallions and female horses. Glenville Pike wrote in his 1976 historic tome Pioneers’ Country that these “bronzed, bearded men”, who were “tough as an ironbark tree”, would load and unload up to 50 mules each day. At the next rest stop, Snow nuzzles me when I share some freeze-dried banana. I ask Tim what it means when a donkey rubs its face on you. “It means it has an itch,” he replies, deadpan.

We arrive late afternoon at Watsonville, pitching our tents by a circle of gums as the donkeys roll in the dust. A mango tree planted here on Anzac Day in 1917 recalls townsfolk who went to war. A long-dead bouquet lies beneath its limbs, dried petals surrounded by drifts of leaves and mango seeds picked clean by birds.

Next morning, after the two injured trekkers are taken to Cairns Hospital, we load the donkeys and set out on today’s 10km leg. Two people down, I’m in charge of Snow and Milo. Milo is lashed behind the more sensible donkey, who will hopefully prove to be a steadying influence.

Our first stop is a windmill on Watsonville’s main street, saved from demolition in 1999 by residents who banded together to fund much-needed repairs. It bears a plaque with the haunting verse A Town That Used To Be, by Watsonville-born bush poet Claude Morris. Further on, we reach the Watsonville Pioneer Cemetery, where the original miners lie, surrounded by grevillea, eucalypts and barren hills. Many died from miners’ phthisis (dust on the lungs). Accidents and suicides claimed others. Conditions were tough, too, on miners’ families: of the 96 historic burials here, 36 are children under 12, with diphtheria and pneumonia among the cited causes of death.

We later pass a lake, and soon, in contrast to the gravel and sand we’ve travelled on so far, we’re squelching through ankle-deep mud. Tim has warned that donkeys dislike such conditions. As if to prove the point, Milo races up the rear to overtake Snow, agitating for the lead. In a heartbeat, I’m tangled in the rope joining the pair and dragged, shouting, through the mud for what’s probably seconds, but feels much longer. The convoy halts. I regain my footing. Tim is beside me, checking I’m okay. “I’m not hurt,” I say, testing my wrists and ankles. It was, at least, a soft landing. “You can’t take some people anywhere,” Tim quips.

We trudge on. Everything aches as we reach our next campsite, near Natural Bridge on the Walsh River, a vast expanse of granite rock formations sculpted by wind and water. By the campfire, Tim gives a lesson in celestial navigation using the Southern Cross. I’m exhausted but can still appreciate that I’ve never seen stars like this before. Scattered across a cloudless sky, the Milky Way is impossibly vast and bright.

We wake next day to the sound of rushing water and braying donkeys. Duffy and Murphy are stamping, raising dust. Snow irritably shoves me with his head. They’re out of sorts because they know what’s coming. Today we must cross the Walsh River. “It’s a big thing for the animals – they don’t like it because they’re naturally hydrophobic,” Tim says. “And if things go wrong, they go wrong in a big way.”

One by one, we edge across a shallow, slippery rock flat, getting little more than our feet wet. But this route is too risky for the donkeys. They must tread the sandy riverbed, which means wading through water that comes up as high as their

pack saddles. With a dispatching team on one side of the river, and a catching team on the other, Tim escorts the donkeys across, one by one. When they’re safely on the other side, he produces a packet of mints and coos: “One for you, Jack, because you went first. One for you, Milo, you were so brave…”

Donkey treks are popular in Europe, but Tim is the only person offering them in Australia. “It’s not your everyday holiday, but it’s a chance to work with big draught animals,” he says. He’s utterly at ease leading them – and us – through territory where, more than 100 years ago, gun packers like Manny Borghero earned good money going where horse-drawn wheeled vehicles couldn’t.

Donkeys didn’t carry enough to be commercially viable long-term for the packers, but Tim prefers them. “They’re easy to train, they’re docile, they’re small. And they like people, whereas mules don’t necessarily like people,” he says. We follow a bush track uphill and over exposed rock to a spot dubbed Little Hells Gate. Located at an altitude of more than 800m, it yields the first phone reception in two days. Through this, we learn one trekker sustained two fractured ankles; the other was released after the all-clear from a CT scan.

Breathless and sweating, we follow Tim along tracks peppered with so much loose rock that the downhill descents become tests of balance “It’s rugged country,” he says, reading our minds. “It makes Victoria look like a frigging mattress.”

At our final rest stop, someone tells Tim there’s something crawling on his hat. He removes the well-worn Akubra, observes a small green caterpillar inching around the rim, and gently positions it so it can climb off onto the branch of a cypress pine.

“It’s a steep descent to our campsite from here,” he says. When Tim says something’s steep, you’d better believe it. Our reward, though, is Rocky Bluffs. The wild beauty of this isolated, windswept stretch of sand and granite on the Walsh River, 10km downstream from where we were last night, takes my breath away.

During dinner, Tim breaks the news that last year’s wet season has washed away the sand bank the donkeys need to cross the Walsh River tomorrow. “The only alternative is deep water, over boulders and rocks, and the risk of a donkey breaking a leg is just too great,” he says. Come first light, Tim plans to scout around for another route, but this development means we may not be able to reach Stannary Hills, where our next rations are waiting.

“So, what’s Plan B?” someone asks.

“I’m still working on it,” Tim says. “But all those leftovers might become very essential shortly.”

During breakfast, Tim confirms there’s no safe way the donkeys can cross the Walsh River. That means Stannary Hills is off the itinerary. Instead, we’ll go back the way we came. Tim’s friends will then drive us back to Watsonville.

Before setting off, we tour the heritage-listed remains of Rocky Bluff Battery, a processing plant for the Stannary Hills Tin Mining Company, which operated for barely 20 years from 1903. We tread single file along an overgrown path strewn with fallen Burdekin plums. This was the main thoroughfare, aptly named Ruffashell Street – pronounced ‘rough as hell’. It was so unnavigable that the only thing to ever pass over it was a wheelbarrow.

The rest of the day is spent tackling the previous day’s journey in reverse. Eventually, we arrive at a property owned by a pig farmer who’s agreed to agist the donkeys until Tim can collect them the following week. Taking the donkeys’ lead ropes for the last time, we usher them into a 2ha paddock.

Milo peers at me through the fence palings, but otherwise there are no lingering farewells. As we climb into 4WDs for the journey to Watsonville, I feel bereft.

Next morning, we’re conveyed by car to Irvinebank, a time-capsule town 13km away. Behind the wheel is Diane Delaney, who delivers a running commentary on the miners’ cottages and other heritage buildings we pass on the way to our campsite beside McDonald Creek. “We try to look after our little town because the history here is astounding,” she says.

As caretaker Peter Shimmin takes us through Loudoun House Museum, built in 1884 as the family home of founder John Moffat, the wooden floorboards creak and sigh. “This was the offices for his empire, which [included] Mount Garnet, Chillagoe, Mount Molloy, Mount Carbine, Stannary Hills, and 20 odd towns that don’t exist at all today,” Peter says.

Moffat was known for his benevolence. “The school children went home at night and said their prayers, and at the end of their prayers they’d say, ‘And God bless John Moffat,’ because he provided work for their fathers,” Peter says.

We also visit Brian’s Shed where former miner Brian Perkes maintains an impressive assortment of historic machinery and memorabilia, but he doesn’t consider himself a collector. “I just don’t throw anything away,” he says.

As the sun slides beneath the hills, Tim points out whispery mare’s tails in the sky. “That means there’s cold weather on the way,” he says.

The smell of pancakes cooking over the fire takes the edge off the morning’s chill. It’s time to return to Cairns – to flushing toilets, running water, refrigeration, wi-fi, and food that can be summoned with a phone call. I feel a tug of resistance. Gruelling though it has been at times, chasing the ghosts of the packers and early pioneers has opened my eyes to the lesser-known history of my home state and has enlarged my view of what I’m capable of doing.

“There’s this legend that [Australians are] of the bush,” Tim says. “Everybody wants to be The Man from Snowy River, but it’s all superficial. People have forgotten how to live with the bush and not be scared of it.”

Back in my Cairns hotel, I take a hot shower, order room service and sink into a cloud-soft bed. But it’s all too easy, too ordered, too quiet. I miss the donkeys, shifting and stamping and braying in the dark. There’s a video clip on my phone from the first night in Watsonville, when they were all loudly impatient for dinner.

I find it, put it on loop, and finally fall asleep.

Denise Cullen was a guest of Wilderness Expeditions, Getaway Trekking and Tourism Tropical North Queensland.