Training AI to listen to Aussie wildlife is a bellow and a hoot

If you go down to the woods today, you’re sure of a big surprise… for in the eucalypt forests of north-eastern NSW there’s a sound that shatters the silence. It’s unnerving and according to Principal Research Scientist Brad Law, it’s seldom heard.

“It mostly happens at night, mostly… around midnight,” Brad says, “which is why the majority of people have no clue about it.”

So what is disrupting the midnight silence?

“During their spring breeding season, male koalas bellow loudly to advertise themselves to females and other males,” Brad says. “While koalas can bellow at any time of the day, remote recorders deployed in forest have revealed they most often do so in the hours around midnight when most people are in deep sleep and so they commonly go unheard.”

_________________

Australia’s wildlife produces an array of wonderful sounds and, according to Brad, those sounds are becoming increasingly useful for ecologists. And new technology is helping capture and process much of this information, leading to an improved understanding of otherwise difficult-to-see animals. “This technology is turning out to be a game changer in helping us monitor the changing status of many of our unique species,” Brad says.

“The method of recording and identifying wildlife sounds is often referred to as ‘passive acoustics’ and it’s a rapidly evolving field. While the approach has been in use for many years with bats and frogs, it is increasingly being used for other taxa.

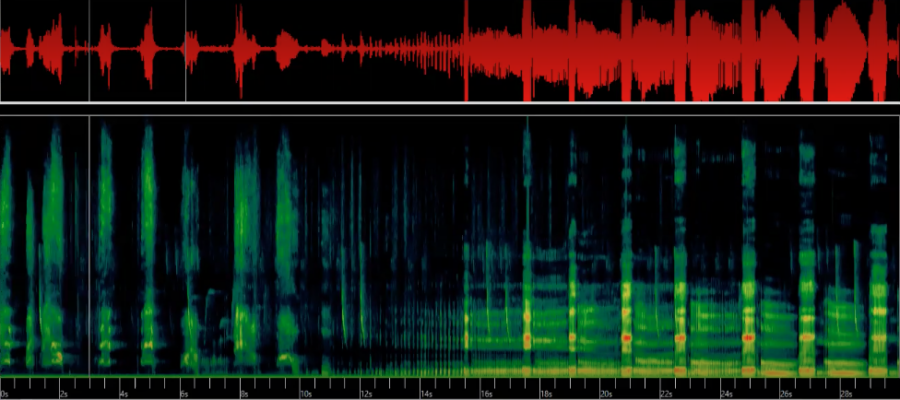

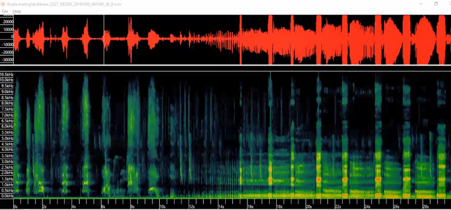

“In the past 10 years or so, hardware that can be programmed with unique recording schedules for extended field deployments has become readily accessible. The biggest challenge today is processing the vast quantities of data that are recorded.”

Automated identification of targeted species is key, says Brad, and using artificial intelligence (AI) is currently the most promising approach for recognising sounds produced by different species.

“This involves collating extensive training data from different regions and testing in real-world situations. It’s a similar approach to human-speech recognition, but for speech you don’t have the difficulty of all the background environmental sounds and, of course, there are millions of examples available for training algorithms.”

Cue the northern NSW koalas. The study of these populations is a great example of how passive acoustics is now being used to improve knowledge of a threatened species.

“Since 2015, our acoustic surveys in the hinterland forests of north-east NSW have revealed koalas remain widespread in these often difficult to access areas. By repeating these surveys each year, we have built up an enormous dataset of many thousands of hours of recordings across 224 sites in the region.

“Using an AI algorithm or recogniser for the koala bellow, we have scanned all of our recordings and, importantly, used humans to validate the presence of bellows.”

All of these data allowed Brad and his team to track the trend in the regional koala population over time, with recent analyses having revealed some good news – the koalas in this region have stable, albeit with declines in numbers at badly burnt sites during the Black Summer fires of 2019.

“These fires were the major factor influencing koalas in this region, but declines in numbers were mostly restricted to areas burnt by the worst fires – those with the highest severity. Koalas generally persisted where fires were less intense or where there was a mosaic of severity, and with good rain after the fires, most forests in north-east NSW have recovered well.”

The extensive acoustic datasets that these results are based upon are now being analysed for other iconic forest species, such as gliders and forest owls, many of which are listed as threatened. The first step in the process is training AI algorithms for these additional forest species. Many of these species are cryptic and there are limited examples of their calls available for training, yet an extensive library (the more the better, but preferably hundreds of calls) is needed from a variety of sites and regions to produce a reliable recogniser. Luckily, our acoustic archive has many calls from a range of species that we have identified during our koala work, along with some additional targeted recordings for some species (e.g. masked and barking owls).

“Our team has now trained recognisers for 10 species,” Brad says. “Using these AI recognisers to analyse our acoustic archive is a work in progress, but it’s clear, going forward, that acoustics will be a powerful addition to methods available for monitoring wildlife.”

Until our analyses from the last seven years of recording are completed, look and listen to this amazing variety of sounds from several of our less easily seen forest species. They range from the loud bellowing of a koala to dog-like yapping of the sugar glider, the falling bomb of the sooty owl and the deep woo-hoo of the powerful owl.