Python parasite pulled from Australian woman’s brain

It was in January 2021 that a 64-year-old woman from south-eastern New South Wales started experiencing symptoms of abdominal pain and diarrhoea, followed by fever, cough and shortness of breath.

“In retrospect, these symptoms were likely due to migration of roundworm larvae from the bowel and into other organs, such as the liver and the lungs,” says Canberra Hospital’s Director of Clinical Microbiology and Associate Professor at the ANU Medical School, Karina Kennedy.

But at the time, after respiratory samples and a lung biopsy were performed, no parasites were identified.

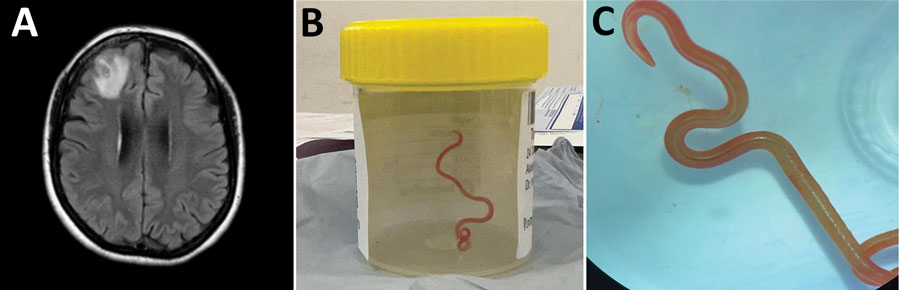

By 2022, the woman – who does not wish to be named – was experiencing forgetfulness, impaired thought-processing abilities, and depression. It was then that an MRI scan revealed an atypical lesion on her brain.

This atypical lesion turned out to be an eight-centimetre long roundworm… and it was still alive!

A world first

Researchers at The Australian National University (ANU) and Canberra Hospital have since confirmed the woman’s case as the world’s first.

“This is the first-ever human case of Ophidascaris to be described in the world,” says leading ANU and Canberra Hospital infectious disease expert and co-author of the study Associate Professor Sanjaya Senanayake.

Carpet pythons (Morelia spilota) are the most common known host of Ophidascaris robertsi roundworms.

“Normally the larvae from the roundworm are found in small mammals and marsupials, which are eaten by the python, allowing the life cycle to complete itself in the snake,” explains Associate Professor Senanayake.

“To our knowledge, this is also the first case to involve the brain of any mammalian species, human or otherwise.”

The woman likely caught the roundworm when collecting Warrigal greens, a type of native grass, researchers have surmised.

The parasite typically lives in a python’s oesophagus and stomach, and sheds its eggs in the snake’s faeces.

It is thought carpet python faeces were present in the area the woman gathered the Warrigal greens, beside a lake near her home.

“The patient used the Warrigal greens for cooking and was probably infected with the parasite directly from touching the native grass or after eating the greens,” the study concludes.

Rise in zoonotic diseases

Associate Professor Senanayake says the case highlights the danger of diseases and infections passing from animals to humans, especially as our habitats increasingly overlap.

“There have been about 30 new infections in the world in the last 30 years. Of the emerging infections globally, about 75 per cent are zoonotic, meaning there has been transmission from the animal world to the human world. This includes coronaviruses,” he says.

“This Ophidascaris infection does not transmit between people, so it won’t cause a pandemic like SARS, COVID-19 or Ebola. However, the snake and parasite are found in other parts of the world, so it is likely that other cases will be recognised in coming years in other countries.”