This ground-breaking Aussie study told the world ultrasound and IVF are safe

It’s known as the Raine Study, is based in Perth and has been collecting inter-generational data from thousands of participants for 33 years, investigating a huge range of health issues from fertility, to diet, and developmental learning.

The Raine Study began in 1989, when 2900 pregnant women volunteered to take part in research looking at the effects of ultrasound during pregnancy. That original ground-breaking research revealed to the world that ultrasound has no ill effects on the health of newborns – a revelation that, of course, has helped millions.

Remarkably, in the 30-plus years since, the Raine Study has continued to record the health of those original participants and their children, following two generations.

Now, the Raine Study is set for two more world firsts.

From last month until at least the end of 2025, an ongoing component of the Raine Study called The Generations Follow-up will proceed for a record 18th time, investigating the health of those generations participating in the Study.

The Study has also announced it will be adding an unprecedented third generation to its research, thanks to funding recently awarded by the Channel 7 Telethon Trust.

Charlotte Diaz grew up in the Raine Study, with generations of her family involved.

Family matters

“I’m what they refer to as a Gen2 participant,” Charlotte explained to Australian Geographic. “My mum, who is

Gen1, was the person who got me involved in the study.

“Then my grandmas… were involved through the breast density studies, [and] they’re referred to as Gen0.”

Charlotte has a two-year-old daughter who is now also being recruited into the study. “We’re really excited to see [her] involved as a Gen3,” she said.

Raine Study participants get a rare insight into the intergenerational health of their families, and potentially advanced knowledge of any health issues.

But, for Charlotte, the benefits are more personal. “As a participant, the [Raine research] team always make you feel so special. They really do make you feel like you’re a part of a family.”

Decades of data

The sense of community and family felt by Raine participants might be why the Study has one of the highest retention rates for any similar research.

“They’re almost like my children,” said Alex D’Vauz, the Raine Study’s Senior Data Manager. “I’ve watched them grow from prepubescent 14-year-olds to 33-year-olds.”

For more than three decades, 71 per cent of all participants have remained with the study. That’s allowed its researchers to collect a huge volume of information.

“Over the last 33 years, we’ve collected over 30,000 phenotypic data points and 30 million genetic data points from each of our participants, and have a total of more than 170,000 biological samples” said the Raine Study’s Scientific Manager, Blagica Penova-Veselinovic.

All that information is meticulously stored and curated by Alex and her team. “It’s first-class, gold-standard data that researchers get,” she said. “They can apply that to their projects and publish findings that are innovative and of the highest standard.”

The power to make a difference

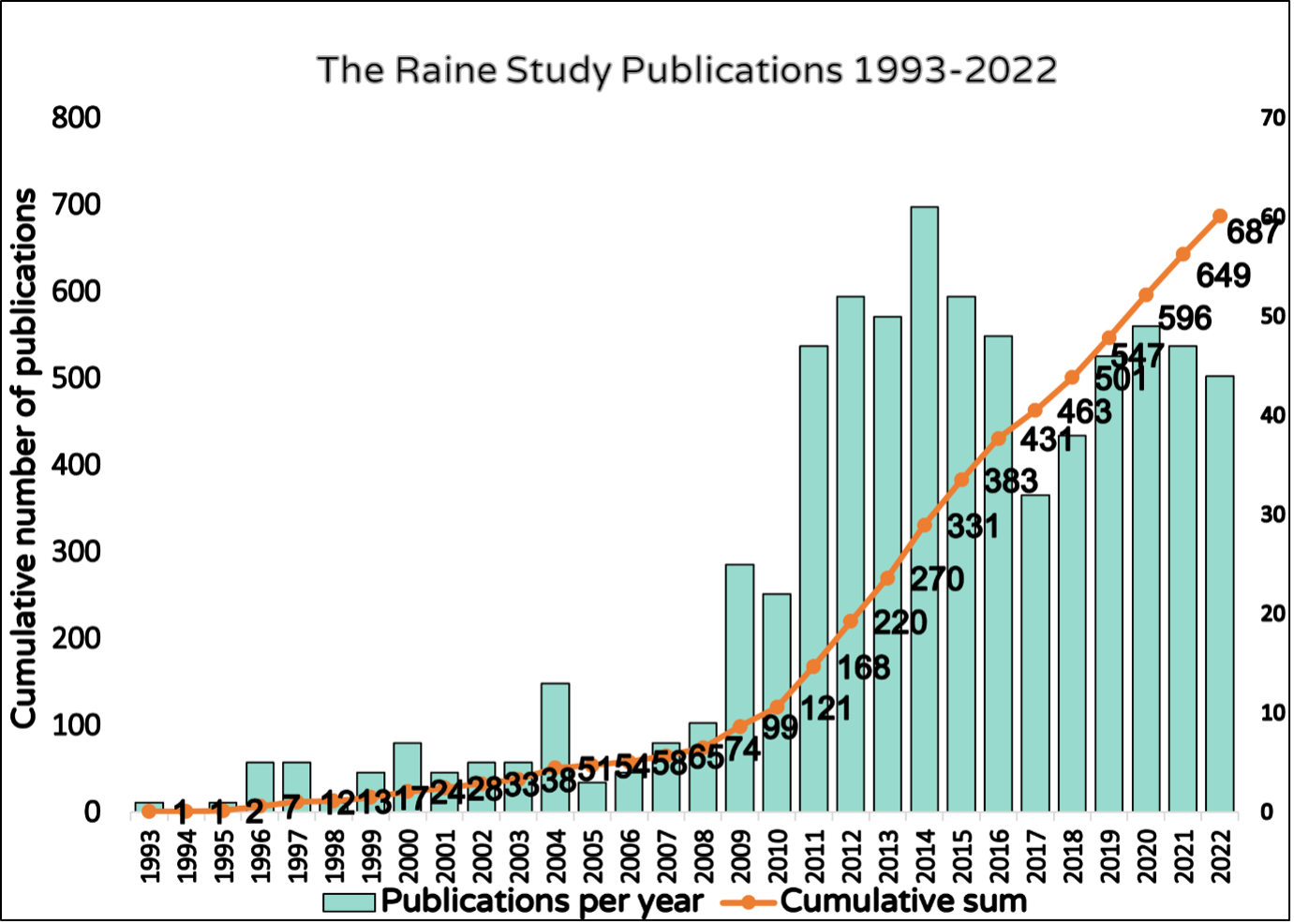

The Raine Study data is a powerful resource and, so far, it’s been used in more than 600 peer-reviewed research papers contributing towards scientific discoveries as well as public health policy.

To access the data, academics need to clearly demonstrate what they hope to achieve by using Raine Study data. “They have to put it in perspective of, how can it make someone’s life better, or how [their] research will influence policy?” Blagica explained.

In 2021 and 2022, six studies led by Professor Roger Hart from the University of WA, looked at the longer-term health outcomes of children conceived using Artificial Reproductive Technology (ART) such as IVF, comparing them to their similar aged naturally conceived counterparts from the Raine Study.

By using Raine Study data, the research team was able to demonstrate that longer-term health outcomes should be no different to the general population, providing comfort worldwide for IVF-born people, their families and couples considering or undergoing IVF.

“The Raine Study was instrumental and integral in sending that message of reassurance,” Blagica said.

The list of public health findings coming out of the Raine Study is extraordinary. They range from linking smoking during pregnancy with developmental learning disorders in childhood, to showing that breastfeeding reduces the chance of middle ear infection in young children.

Raine Study data has also helped to show links between asthma, allergies and immune system function.

It’s even been able to show that children who grow up without a liquor outlet in their neighbourhood drink less as a young adults.

Looking at future possible outcomes, the Raine Study may provide invaluable data on the long-term population effects of public health issues such as COVID and climate change.

This year, Raine Study researchers want to link the data with commonwealth and state administrative databases. Such partnerships could provide a new level of understanding, where inequalities in national public health and wellbeing can be approached head on.

“We all talk about equity, but not much is put in practice. If we have the data to support it, it will be much easier for the politicians to hear you out and to say this is based on fact,” Blagica said.

Despite its significant contributions to public health, the Raine Study receives no governmental funding to support its core day-to-day costs.

“My wish for the Raine Study as a participant and especially as a mum of a future participant is that [will be rectified],” Charlotte Diaz said, adding that she hoped the Raine Study becomes recognised “as one of the true gems of research”.