Step out of your vehicle about 30km off the Sturt Highway near Balranald, near the Victorian border in south-western New South Wales, and it’s like someone has opened a window and let in a flurry of birds. Colour, movement and water surround both sides of the road and you know you’ve arrived at Gayini (formerly Nimmie-Caira), an 88,000ha property nestled in the southern Murray-Darling Basin.

“Wait till you see the pelicans,” says Jamie Woods, Gayini land manager and Nari Nari Traditional Owner (TO). Close by, about 20,000 pelicans are breeding in a colony after recent rains; an awe-inspiring sight of thousands of bulbous eyes consuming the landscape all the way to the horizon.

Part of the Lowbidgee floodplain, the largest remaining area of wetlands in the Murrumbidgee Valley, Gayini (the Nari Nari word for water) is of international conservation significance. It provides feeding and breeding habitat for many species of freshwater birds, including the straw‑necked ibis, royal spoonbill and little pied cormorant. This flat, largely arid landscape is surrounded by winding, intricate and often colourful wetlands dotted with thousands of visiting birds. The most recent flood has inundated more than 70 per cent of Gayini, helping revive parched pockets within the property. “You see why it’s so special to the mob,” says Nari Nari TO Rene Woods.

In 2020 the property was handed back to the Nari Nari by the NSW government with the support of The Nature Conservancy (TNC), a not-for-profit organisation with global reach. “The combination of flood and years of restoration work is paying off. We’ve seen the return of threatened species like the southern bell frog and, of course, the thousands of birds that come to feed and breed,” Rene says.

Richard Kingsford, professor of environmental science at the University of NSW, explains that despite Australia’s reputation as one of the driest continents on the planet, recurring floods are vital to many of the continent’s landscapes. “Without them we wouldn’t have a living Australia,” he says. “It’s what makes our country tick.”

Richard is part of a research consortium for Gayini that brings together First Nations‑led conservation, TNC, the UNSW Centre for Ecosystem Science and the Murray Darling Wetlands Working Group. His major concerns for our wetlands are climate change and the impact of water extraction from rivers.

“Much of what happens to our rivers is guided by what occurs upstream,” he says. “This leaves our wetlands vulnerable in the face of an imminent bust period, and so the big question is: what policy loopholes are going to impact water management in the future?”

There are good reasons to keep Australia’s many wetlands healthy, not least because they are key areas of productivity that support, sustain and influence countless species well beyond their geographic boundaries.

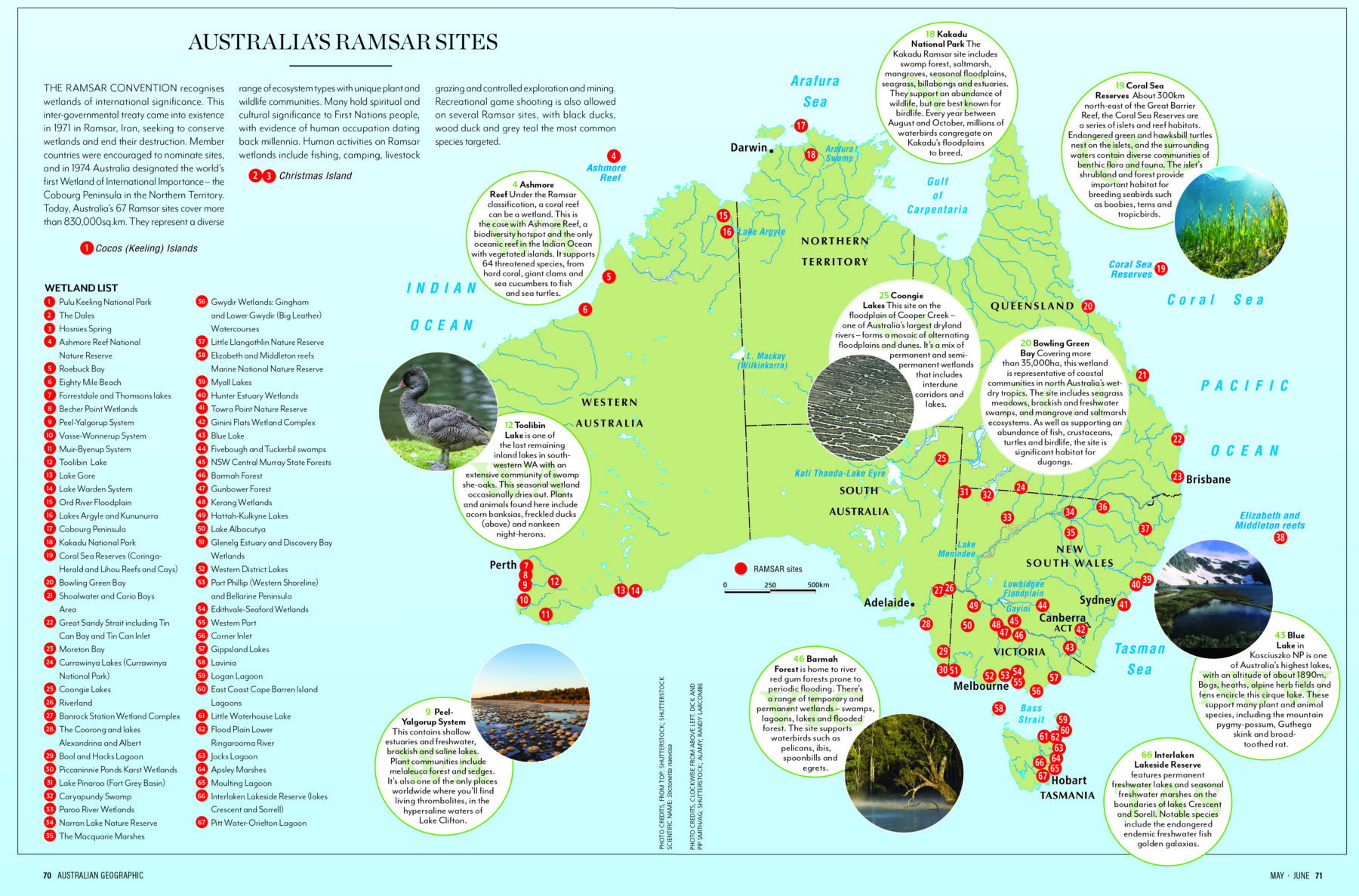

Australia boasts an abundance of unique, diverse and significant wetlands, including 67 Ramsar sites classified as being of international significance under the Ramsar Convention of 1971. These include Roebuck Bay in Western Australia, the Cobourg Peninsula (Australia’s first Ramsar site) and the World Heritage Kakadu National Park, both in the Northern Territory. Key issues for such places include rising sea levels and excessive saltwater inundation.

West of Kakadu and along the channels of the Mary River, the effects of rising sea levels are obvious. An expanse of dead paperbarks litter the landscape and a forest of dead trees lines the river and its tributaries, caused by salt water flowing into the system. Climate change is understood to be a driving force, and modelling by CSIRO indicates that all the freshwater floodplains around Kakadu will experience a rise in levels of sea water by 2132. “We can’t do anything about sea level rise,” Richard acknowledges. “But how the connected areas of fresh water are managed will help decide the fate of these places. Salt water will push into a river system, so if you start taking the fresh water out, there is

no flow to keep the sea at bay and the system will change. There are things we can do to manage these events.”

Less than two hour’s drive south of Melbourne, the 590ha Tootgarook Wetland is the largest example of a shallow

freshwater marsh in the greater Melbourne area. These habitats have been extensively cleared and filled in across Victoria, with just 4 per cent of the state’s original wetlands remaining. It’s located on land owned by local business-owner Rob McNaught,who has spent more than 10 years working with conservation groups, such as Trust for Nature, to protect and restore the swamp. Species found here include the nationally endangered Australasian bittern and a variety of migratory species, including Latham’s snipe, which flies from as far as Japan and Russia. Although most of the swamp is protected by conservation covenants, a proposed freeway easement still runs through its centre. Rob’s position on this is clear: “Surely times have changed and we no longer need to put a road through one of the state’s most significant and intact wetlands?”

A similar ethos is reflected in several conservation initiatives dedicated to restoring wetlands elsewhere on private land in Victoria. Wirra-Lo, about 320km north of Melbourne near the farming town of Kerang, is a site owned by the Wetland Revival Trust, a not-for-profit established by ecologists Damien Cook and Elaine Bayes. The pair work with the community and TOs to undertake weed control, revegetation work and hydrology restoration. Wirra-Lo is also one of the last strongholds in northern Victoria of the nationally vulnerable growling grass frog.

“A farmer once said to me, ‘If you look after nature, nature can look after you’,” Damien says. “If we use this to guide our work, threatened species and wetlands have a real chance at hanging on during the next drought.”

At Gayini, Rene voices a similar sentiment as he reflects on recent flooding and the Nari Nari’s restoration work. “Bringing the wetlands back to life and undertaking this work has rewards far beyond the animals we see come back,” he says. “It’s also healing our people, our culture, and brings meaningful employment and benefits to an entire community. The focus now is to be as prepared as possible for what the climate may do next.”