Questions raised about Western Australia as site of oldest signs of life

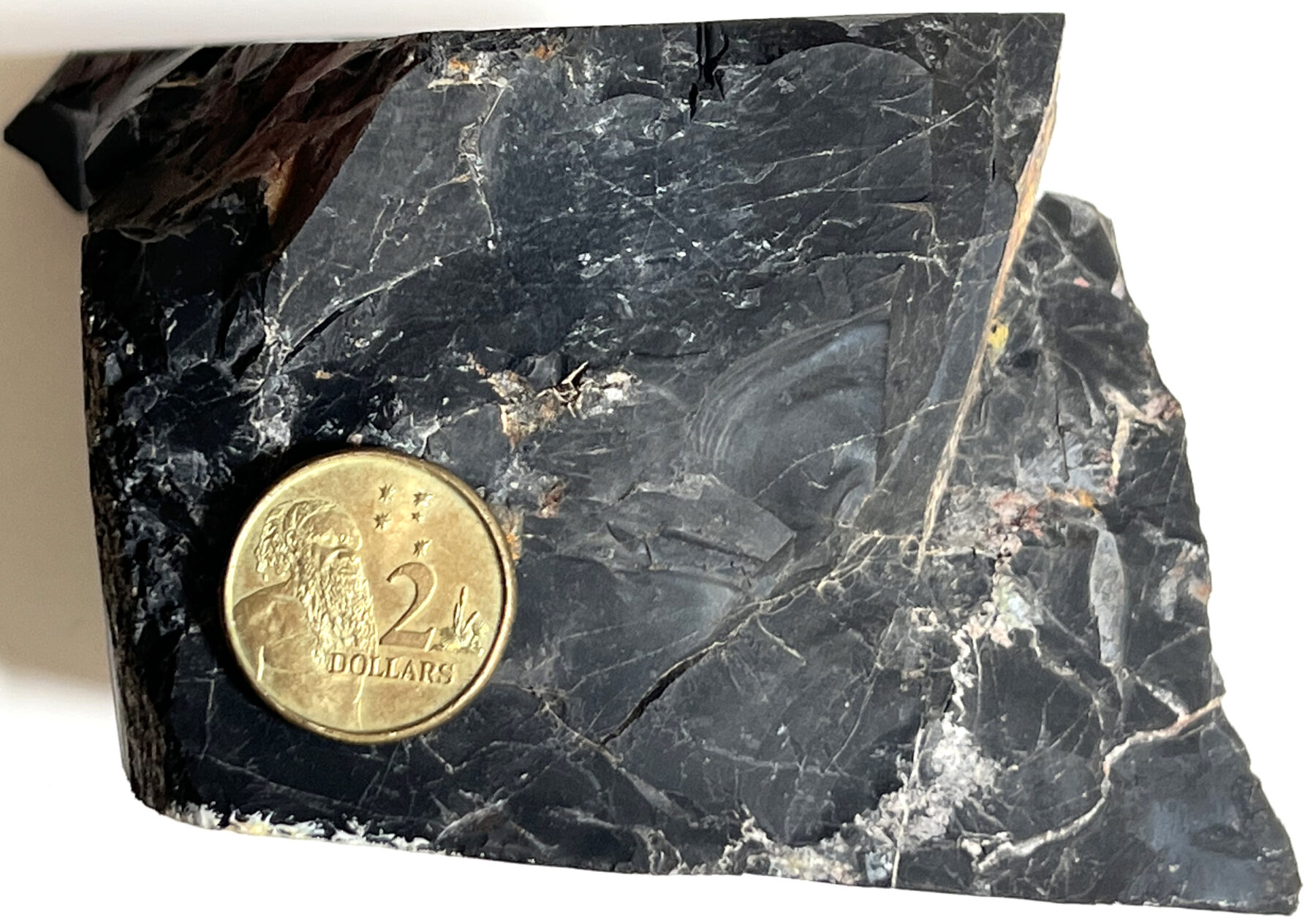

It’s well-known that WA’s Pilbara has some of the world’s oldest and best-preserved rocks, which offer a glimpse of Earth when it was young, and life was just beginning.

In fact, many studies have claimed that organic compounds found in the Pilbara, including some that date back more than 3.48 billion years, are the fossilised remains of Earth’s earliest microbial life – precursors to all life since.

But a new study published in Science Advances questions whether these organic compounds really are evidence of life at all.

The study’s authors, Professor Birger Rasmussen and Dr Janet Muhling, of the University of WA’s School of Earth Science, claim that the carbon compound found in Pilbara rocks, long thought to be the fossilised remains of microbes, may have been misinterpreted.

New look at old rocks

“When we say organic, we don’t really mean living or biological; it’s just carbon-rich compounds,” Birger explained. “The reason we’re sceptical is there are no traditional source rocks for fossils, like organic-rich debris.

“Our work suggests the carbon was not indigenous; it migrated through the rocks.”

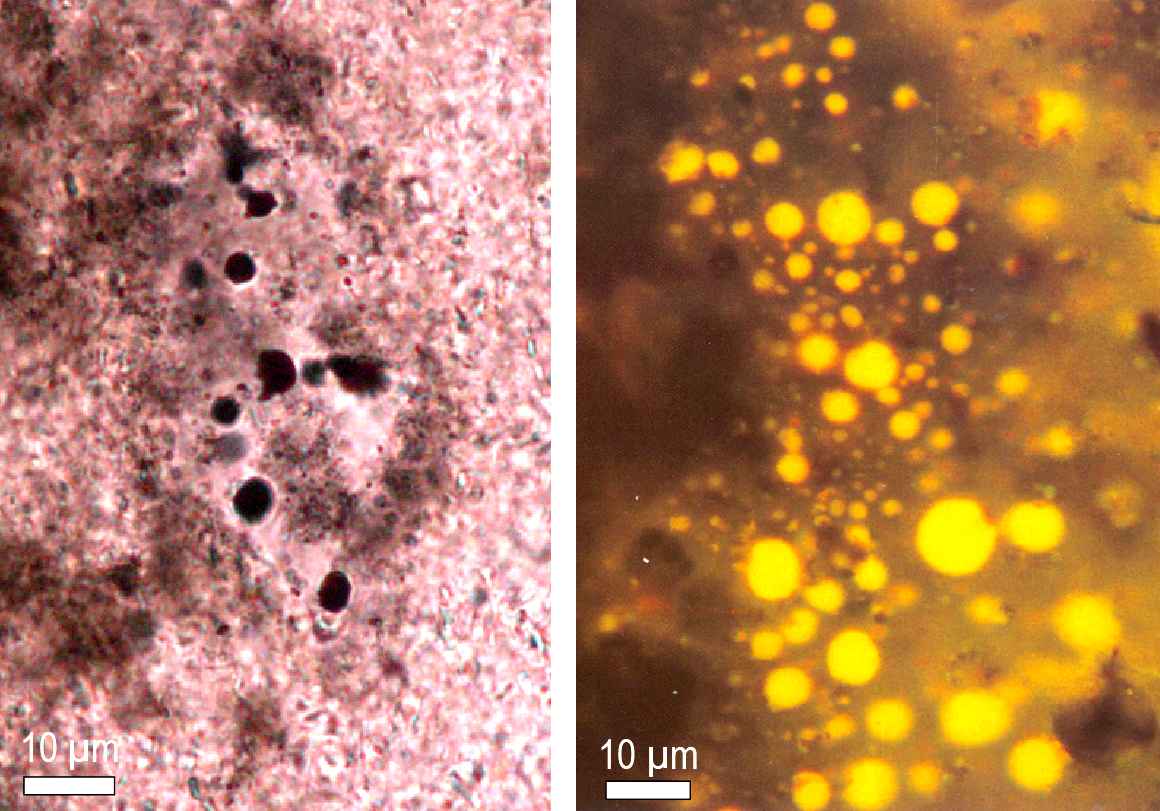

What may have happened is that as seawater passed though lava on the ocean floor it reacted with CO2, creating carbon-rich, oily liquids.

That liquid then flowed through veins in rocks until it was delivered into fine-grained quartz deposits.

There, it crystalised into “oily biomorph” structures that look deceptively like fossils.

“We can’t rule out that some of it is biological,” Birger said. “But these rocks are really lacking the sorts of minerals that give you biological products.”

This new discovery both clarifies and complicates our understanding of life.

It provides a crucial piece of information to one of humankind’s greatest quests – the search for the origins of life.

New look at life

This new interpretation might mean that life on Earth began later than previously thought.

But it’s also possible these carbon-rich biomorphs provided the building blocks for early life to develop.

“The sort of environment we’re looking at is probably producing things such as fatty acids, which could have produced primitive cell-type structures,” Birger explained.

If true, this could have massive implications for how we understand the beginnings of life, not only on Earth but also on other worlds.

Life on Mars

Meteorites from Mars, for example, have been found to contain organic carbon compounds very similar to those identified by Birger and Janet, indicating that similar chemical processes as those on Earth were occurring in Mars’ early oceans.

“In primordial settings, these processes might have contributed building blocks that helped the first cells to emerge,” Birger said.

So, if Mars’ oceans hadn’t disappeared from its surface, similar organic compounds may have contributed to the development of life in the same way that they did on Earth.

Despite these possibilities Birger emphasised it was important to be prudent in our search for life.

“You have to be careful about the sort of shortcut assumption that carbon equals life,” Birger said. “In terms of identifying life, [our new understanding has] made that a little harder.”