Long lost last Tassie tiger remains found in museum cupboard

Researchers recently realised the remains entered the collection of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) in 1936 but hadn’t been properly identified.

The last-known Tasmanian tiger died in Hobart’s Beaumaris Zoo on the night of September 7, 1936.

“For years, many museum curators and researchers searched for its remains without success,” researcher Robert Paddle said.

“No thylacine material dating from 1936 had been recorded in the zoological collection, and so it was assumed its body had been discarded.”

But recent inquiries by Dr Paddle and TMAG curator of vertebrate zoology Kathryn Medlock revealed the last-known thylacine’s remains were at the museum.

Dr Medlock said they discovered a taxidermist’s report in the museum’s unpublished 1936/37 annual report which mentioned a thylacine among the list of specimens worked on.

This led to a review of all the thylacine skins and skeletons in TMAG’s collection.

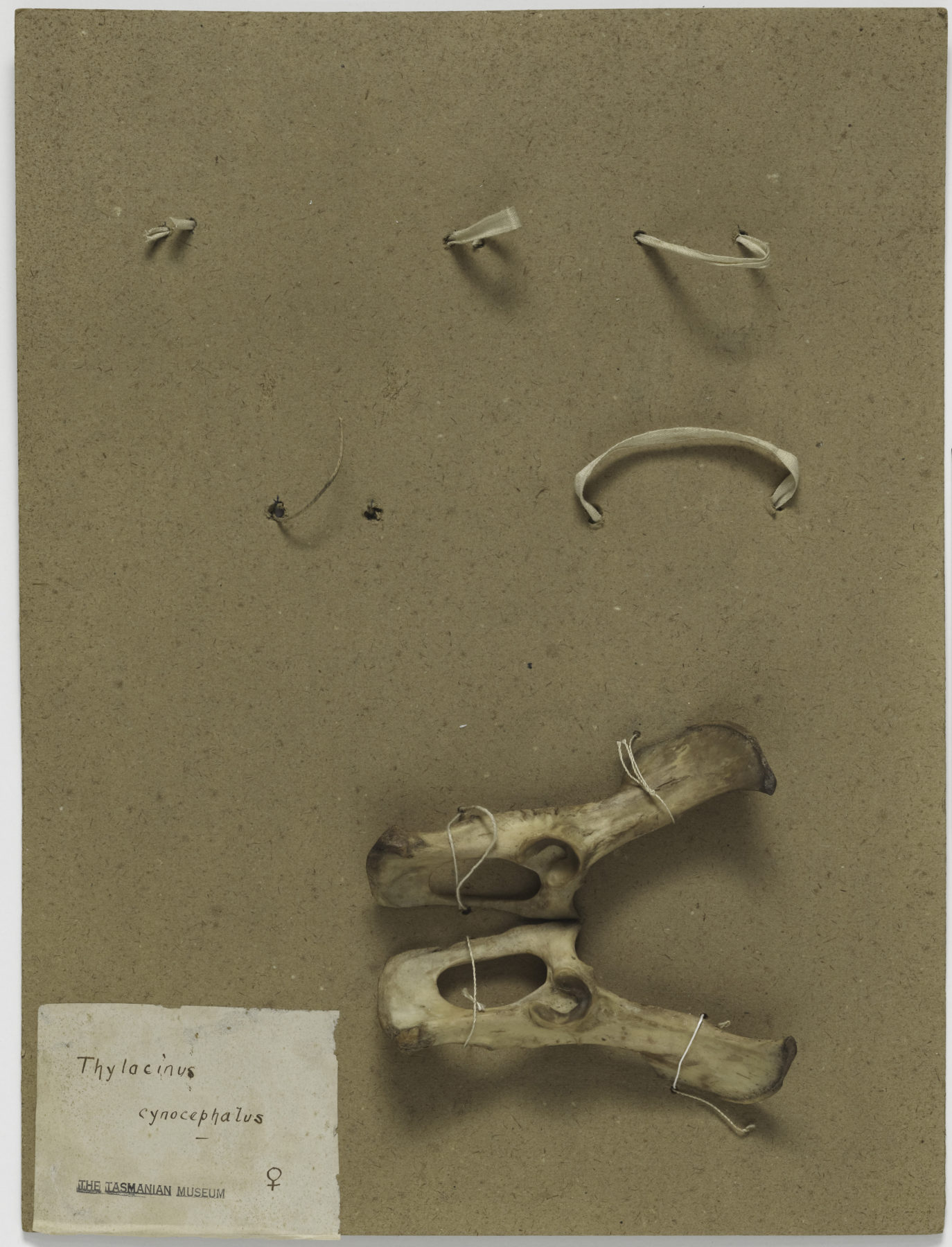

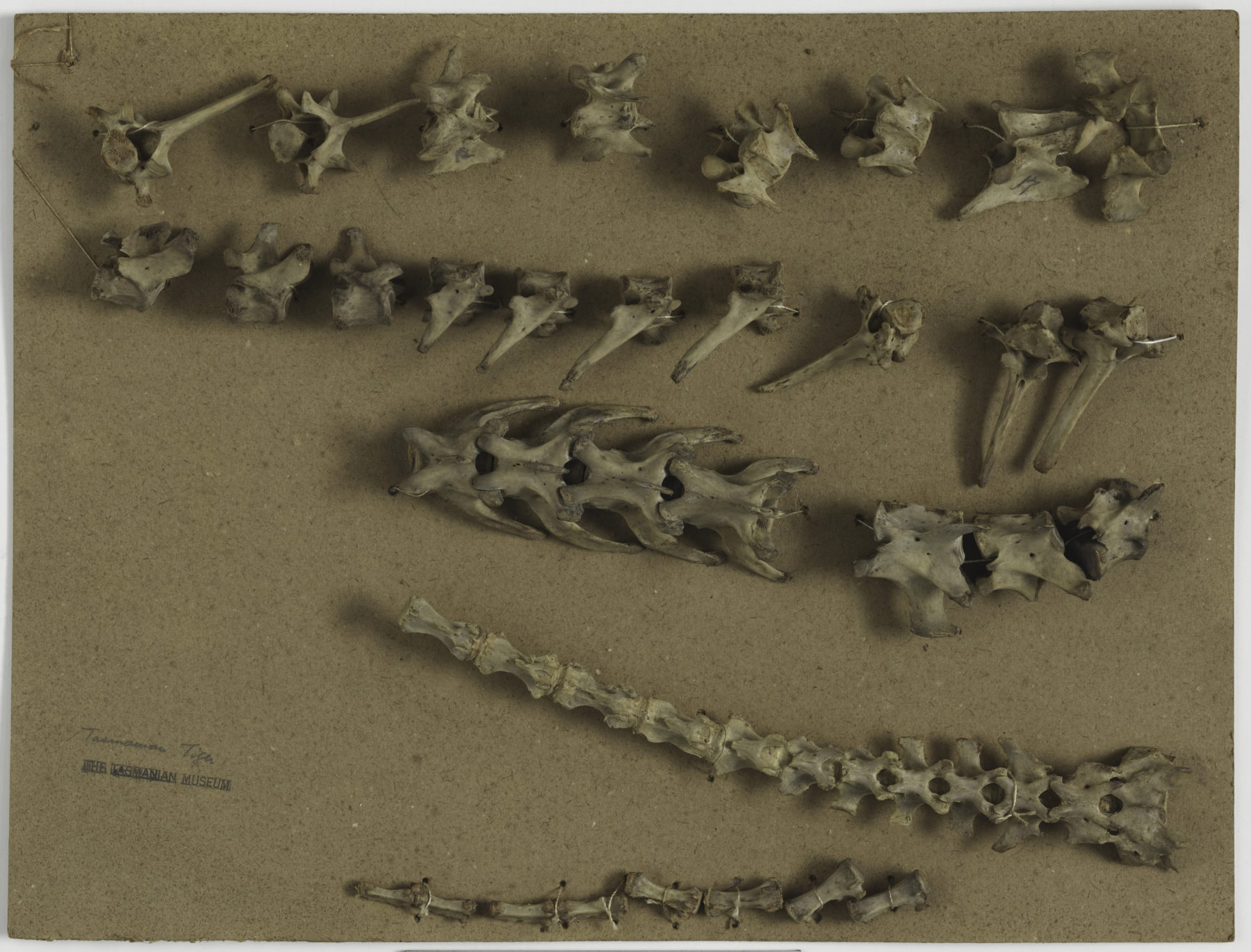

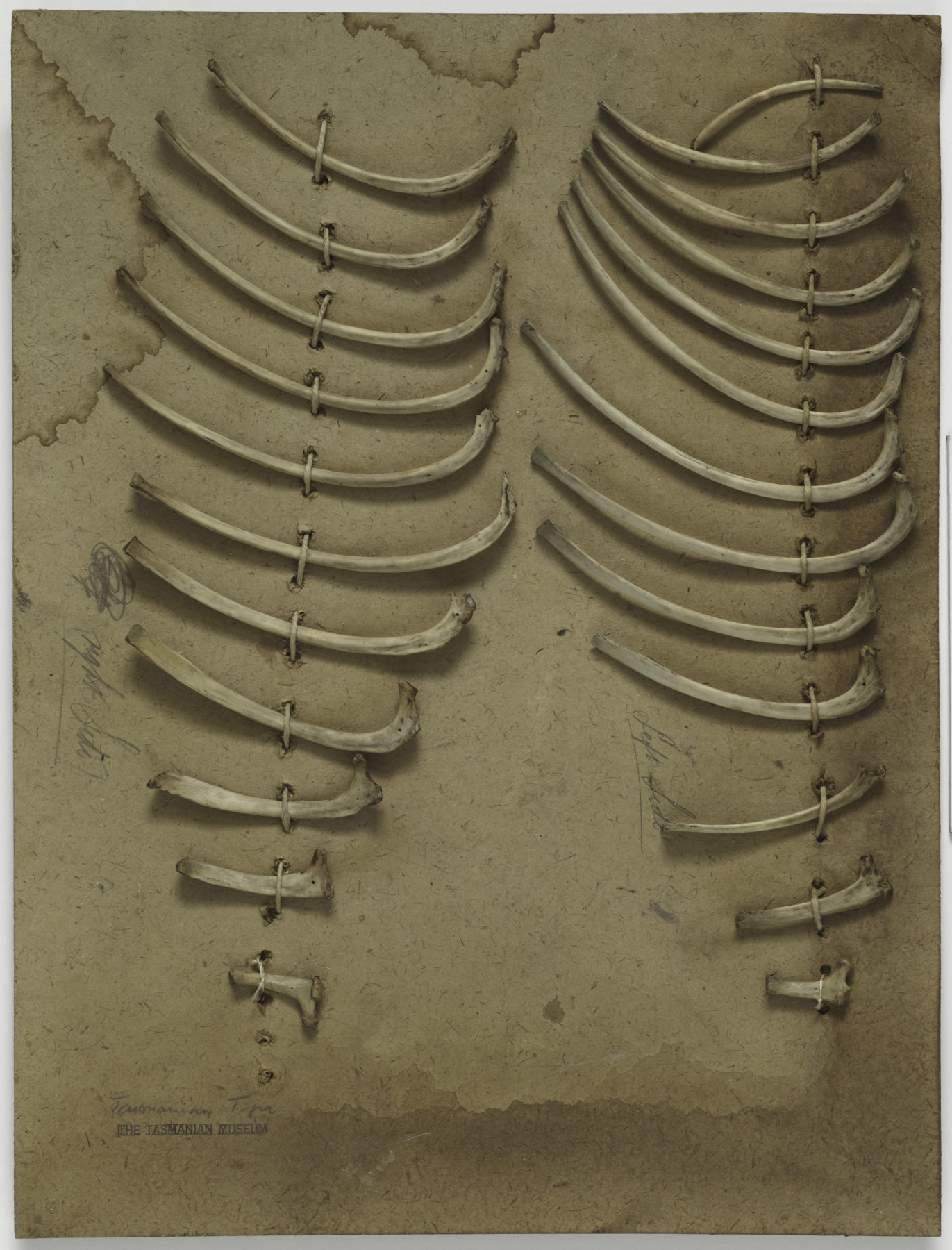

“We tried to work out which specimens we could trace to something. There was just a skeleton and flat skin left over,” Dr Medlock said.

“We were able to determine the specimen … had been prepared by a taxidermist. Not as a research specimen, that’s why it wasn’t recorded, but as an education specimen.”

Dr Paddle said the thylacine in question was an old female that had been captured by trapper Elias Churchill in rugged southern Tasmania and sold to the zoo in May 1936.

“The sale was not recorded or publicised by the zoo because, at the time, ground-based snaring was illegal and Churchill could have been fined,” Dr Paddle said.

“The thylacine only lived for a few months and when it died its body was transferred to TMAG.”

The skin of the last-known thylacine had unwittingly in the past been used to teach students about marsupials.

“It is bittersweet that the mystery surrounding the remains of the last thylacine has been solved,” museum director Mary Mulcahy said.

“Our thylacine collection at TMAG is very precious and is held in high regard by researchers.”

Dr Paddle said the discovery should put an end to thoughts that the last-surviving thylacine was a much-photographed and filmed male, often referred to as ‘Benjamin’.

Bounties were placed on the thylacine, described as being shy and nocturnal, during European colonisation in Tasmania because of worries it was attacking livestock.

The skin and skeleton of the last-known thylacine have been placed on public display at the museum.