Palaeontologist Dr Matthew McCurry apologises that the remote paddock in central New South Wales where we’re standing on this cloudless winter’s morning is so visually uninspiring. The site, which is accessed by a dirt road and protected by locked gates, looks surprisingly ordinary, despite having been the focus of recent worldwide attention.

“It’s dry and it’s flat, with a few sporadic trees spread across a landscape that’s mostly parched grass with occasional thistles – a typical farmscape you’d expect in this part of NSW,” Matt says. Yet this particular nondescript location is being kept top-secret, despite attracting international scientific attention and producing clues that may prove invaluable as Australia and the world grapple with unprecedented global warming.

“Fifteen million years ago [mya], based on the fossils we’ve found here, this would have been dense tropical-like rainforest with a thick canopy of plants competing for sunlight,” Matt explains. At its heart was a polluted, rust-red billabong – “a small waterbody flooded with iron, possibly an oxbow lake”.

Matt picks up one of the heavy black-and-ochre fragments of rock littering this part of the paddock that make it such a bugger to plough. This material is the reason why a crack team of fossil hunters – both professional and volunteer – have driven in a convoy of four-wheel-drives early this morning from nearby Gulgong, the heritage-listed goldrush town that appeared on the first $10 note in 1966 when Australia introduced decimal currency.

These rocks may not contain gold, but to palaeontologists they have much richer veins to reveal. The life forms they encase speak of a vastly different Australia, from a time when our island continent was drifting imperceptibly but irrevocably northwards in its post-Gondwana divorce from Antarctica. That’s when a chain of volcanoes burst through Earth’s crust, leaving remnants that can still be seen in a north–south divide that includes NSW’s Mt Warning (Wollumbin) and southern Queensland’s Scenic Rim.

“We know, thanks to geochemical analysis, that the basalts deposited by these volcanoes are the source of the iron here,” Matt continues. “Based on Argon dating, we’ve been able to track the basalt back to around 37mya.”

He points to a still-existing ridge, explaining that basalt is a volcanic-derived rock that spewed from the underworld during the Eocene Epoch (56–33.9mya). “We can still find basalt up there,” he says. “But over millions of years the iron would have leached out of the rock.”

Either in surface water or groundwater, the iron-rich minerals flowed downhill to the ancient billabong, slowly poisoning it. Despite this, the billabong and surrounding forest abounded with life: birds, insects, spiders, fish, flowers, plants, moss and pollen. The Australian Museum–University of Canberra team co-led by Matt know this because of the 15-million-year-old fossil record they’ve discovered after just five years of forensic investigation here.

Far more is waiting to be uncovered, which is why there’s so much secrecy surrounding the exact location of this scientific site.

Each once-living thing – from busy bee to discarded leaf – was embalmed and entombed, waiting like a prehistoric pharaoh to be majestically restored. The early finds were published in the January 2022 edition of Science Advances, and provide insight into the nature of moist Miocene (23.03–5.333mya) ecosystems.

The paper produced a euphoric response from the worldwide palaeontology community.

Palaeontologists often do their detective work using bones, teeth, tusks and other harder parts of life that frequently become fossils once the rest of a plant or animal is recycled. Two things make McGraths Flat worthy of international attention. First, the Miocene is geologically like the day before yesterday. Dinosaurs were already extinct, megafauna had yet to emerge.

Most fossil species unveiled at the site so far have close relatives still alive in Australia today, although they’re usually thousands of kilometres away in the tropical north. McGraths Flat is a vital piece in the jigsaw of life. Which species adapted to previous climate change, and which perished? What lessons can we learn as we endure accelerated global warming like no other time in human history? Second, this iron-rich rock (named goethite after German polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe) had the ability to encase still-living organisms into red-rock graves ready to be exhumed 15 million years later.

Already the research team has discovered an extraordinary array of soft-tissue exhibits, proving what this island continent gave birth to long before even the first people arrived some 60,000 years ago. Fish-stomach fossils reveal what each creature ate for its last supper the day it died.

Another fossil of a fish tail reveals, under an electron microscope, a baby mussel larva hitching a ride upstream.

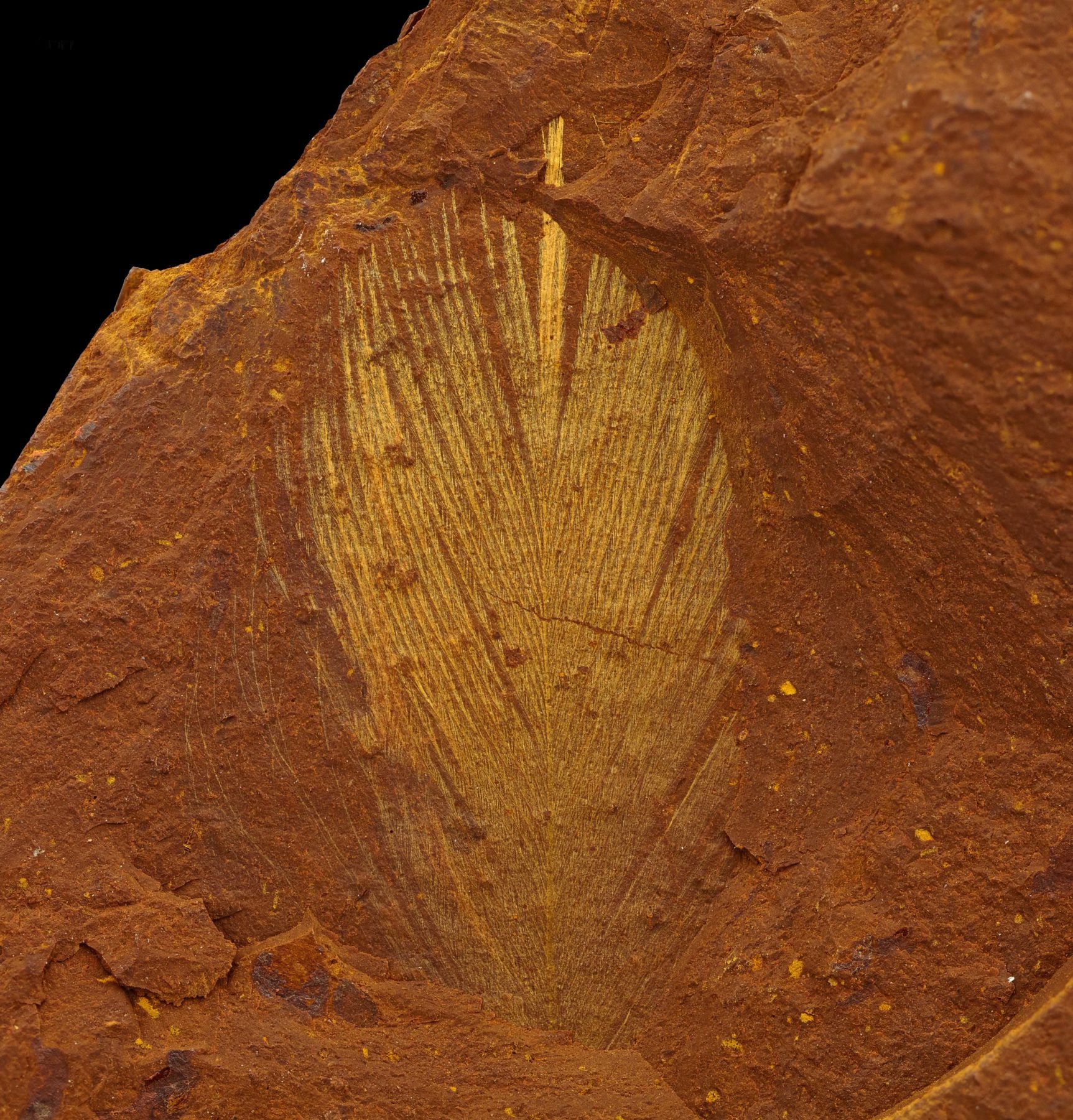

Then there’s the Mona Lisa of McGraths Flat: a prehistoric bird feather. Fossilised bird feathers are rarely found by palaeontologists. They’re too delicate, too easily destroyed. However, the feather the scientists found at McGraths Flat was so wonderfully preserved that they’ve been able to deduce it’s a breast feather from a mid-sized bird that was coloured either red or black.

This morning’s dig begins with an Acknowledgement of Country and health and safety instructions, after which every fossil hunter here has the same ambition: find the rest of the bird that once inhabited this 15-million-year-old billabong.

If there is one thing more elusive at McGraths Flat than the billabong bird, it’s the man the site is named after – cattle-and-sheep farmer Nigel McGrath. “Nigel”, as he’s simply known to every palaeontologist here, whether they’ve met him or not, doesn’t like press attention. To date he’s only given one brief interview – to Julie Power of The Sydney Morning Herald (SMH), when the paper in Science Advances was released.

Nigel’s entire media career consists of just 32 words. Asked what it felt like to have the site named after him, the farmer, whose family have owned this land since World War II, dead-panned: “Most people die before they have something named after them.”

Surely, the SMH reporter asked, Nigel’s children and grandchildren were enraptured by what he’d uncovered. “You know what kids are like,” he replied. “Show them a Game Boy and they are excited. Show them a rock and they aren’t.”

At 78, science and agriculture teacher Robert Beattie is the oldest person on this weekend’s dig. He “retired” in 2002 but still works most days as a casual teacher and has known Nigel the longest. He’s also the man who found the feather.

Before lunch, Rob takes photographer Max Mason-Hubers and me for a drive in a 4WD to another McGrath-owned paddock, where the modern story began. While McGraths Flat is certainly flat, this other site – known as the Talbragar Fish Bed – has magnificent 360-degree views of the central NSW highlands. It sports a faded noticeboard acknowledging we’re standing on “Australia’s Most Famous Jurassic Fish Graveyard”, which dates from 175mya, which is 160 million years before the fossils at McGraths Flat formed.

“If there is any property in the world that has two sites of such importance from two different geological eras, I don’t know it,” says Rob, now elevated to the position (unpaid) of a research associate with the museum. “I’ve been a fossil person since I was six. I first came to this Jurassic site in 1959 with my parents, so I’ve known Nigel from way back. Nigel is a kind, cooperative landowner who continues to allow us on his property because he realises how important this site is for science,” Rob adds, explaining that one day about five years ago the museum team was packing up for the day on the Jurassic site when the taciturn Nigel appeared “for a bit of a yarn”. The farmer explained he’d been trying to sow oats, but his plough kept getting damaged by the ultra-hard rocks above and below the surface. So he got a team of his workers to gather what rocks they could and pile them by the side of the farm track. In the pile, he found a fossil of a leaf.

These rocks may not contain gold, but to palaeontologists they have much richer veins.

Unless you’re a palaeobotanist such as Professor David Cantrill, who’s part of this team, leaf fossils don’t attract too much attention. But as the convoy of scientists was passing Nigel’s pile anyway, they stopped and loaded a few of his rocks into their vehicles. “We didn’t think any more of it,” Rob recalls. “Then one of the guys found a perfectly preserved insect in a rock. So we started to dig here at McGraths Flat and immediately started finding more insect fossils. Since then, we’ve worked here instead of at the Jurassic site.”

While we were looking at the Jurassic site, Nigel’s neighbour Matt Hensley, who runs an agricultural fertilising business, had been busy with his backhoe, excavating the next pit at McGraths Flat. “Nigel’s a man of few words, unless you get him down the pub. Then you can’t shut him up,” neighbour Matt says. And is Nigel proud of the palaeontology site he discovered? “Definitely,” Matt says. “Since word got out about this site earlier this year, Nigel has become a local celebrity. I have to remind them I’m the one who digs the rocks out.”

Does Matt enjoy being involved in such a prehistoric project? “Yes, it’s cool,” he says. “They named a beetle after Nigel so I’m hoping they’ll name something after me.” Like what? “Preferably the bird that lost that feather?”

“Join the bloody queue,” comes the chorus from the dig team.

At 25, Ailie Mackenzie is the youngest member of this weekend’s dig team and the only woman. The Macquarie University graduate is technically a volunteer because she’s not being paid for this weekend. However, the self-confessed farm girl – “of course I know how to lock a bloody gate!” – is employed in the museum’s palaeontology department as a digitising technical officer. She’ll be digitising all of the McGraths Flat finds.

“This dig is much more organised than most of the digs I have catalogued,” Ailie says. “Many past digs don’t contain

the details of the location where they were found, the date or the taxonomy.”

But on this dig things are different, thanks to Lachlan Hart. The museum research assistant has volunteered to document, wrap and store every find, after copious group consultations over the field microscope. “It sure beats smashing rocks for 12 hours,” he says. Lachlan is currently studying for his doctorate into an extinct group of large amphibians that lived in Australia and elsewhere, notably during the Permian and Triassic.

“My highlight from this site would be to find a prehistoric frog,” Lachlan says. “I’m not really a spider man.” But he knows that discovering even a tadpole is unlikely.

Cameron Slatyer is struggling on the first morning of the dig. Unlike the rest of the team, he refuses to sit on a stool, knowing his knees will be crippled by the day’s end. “But at least I won’t stuff my back up, and I have a mixed grill to look forward to,” he says. Whenever a fossil is found, Cam is summonsed as “our insect man”. McGraths Flat is his first dig, but he has a wealth of field experience, not least from his current role as program manager of CSIRO’s National Biodiversity Data Initiatives.

Cam explains he’s worked on modern rainforest not dissimilar to what we’re digging up from 15mya.

“It’s like walking across a modern rainforest floor,” he says. “The cicadas are my favourite fossils. In summer you can find dead cicadas anywhere on the ground in a tropical rainforest.”

Cam and his colleagues are gathered under the shade of a single she-oak with a mound of discarded rock at its base. Each pit is scrupulously pegged, identified on GPS, dug to a depth of 1.5–2m and the rocks extracted as the backhoe reveals its treasures.

Then, when the museum’s Matt and Michael are happy with the haul, neighbour Matt and his machine cover in the scars. This morning’s treasure will be labelled “Pit H”, although the dig team won’t finish splitting the rocks left over from “Pit I” before they leave on Sunday afternoon.

German-born Dr Michael Frese admits he’s not a trained professional palaeontologist, although as a kid he had one of the biggest rock collections in his small village north-east of the Rhine. He is a lecturer in immunology and microbiology at the University of Canberra. But, importantly, he brings electron microscopy skills to the team. Michael has access to the nation’s finest equipment at the Australian National University’s Centre for Advanced Microscopy, in Canberra.

“A few digs ago we found a 2cm spider,” Michael says. “I knew immediately it would be the largest fossilised spider ever found in Australia, and probably the world. It’s closely related to the Sydney funnel-web spider we know today.”

Fossils offer a window into past climates and hint at what might happen in the future.

As the hammering and chiselling continues on the dig site around us, Michael shows me the presentation he’s prepared on McGraths Flat for school and community groups. You may have seen the wonderful images NASA posted from its recently launched James Webb telescope of long-gone galaxies millions of light-years away. What Michael’s images reveal in an outback paddock is the exact opposite, but it’s equally awe-inspiring.

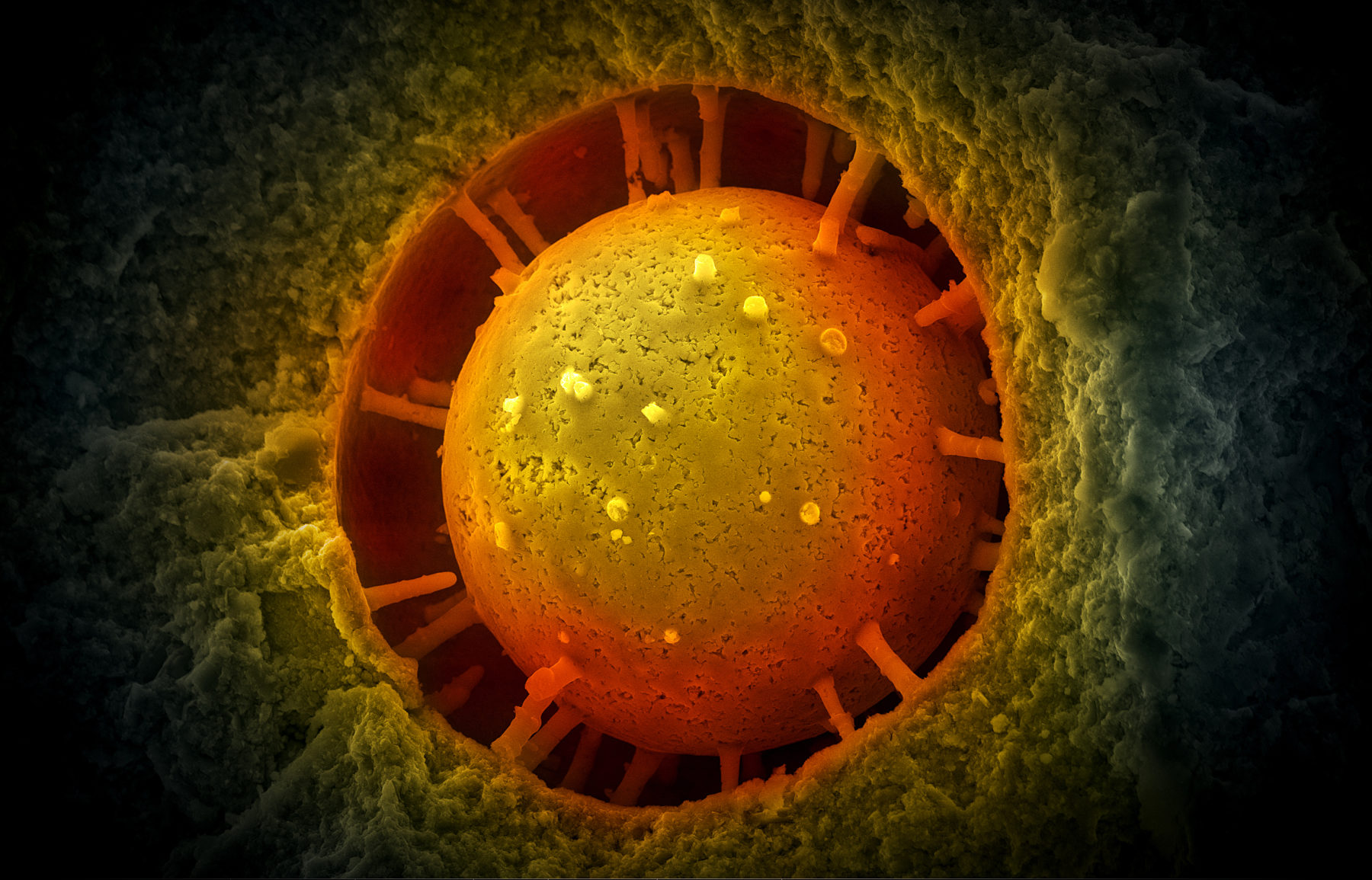

“I call this the Death Star, from Star Wars,” he says, concentrating on his favourite image. It’s an artificially coloured scanning electron microphotograph of a fossilised single-cell organism of unknown origin. At just 55 microns (.055mm), this “Death Star” is invisible to the human eye.

Michael can’t give too much detail yet about his favourite find at McGraths Flat because it’s currently the subject of a scientific paper under review. So, let’s call it a sawfly. “I knew when I found it that this was a career-defining moment,” he says. “They’re never preserved to this extent. But look at this. See the head, the antennae, the pincers?” It’s highly impressive. “Now comes the interesting bit,” Michael continues. “I put its head under an electron microscope and found it’s covered with pollen. My fellow scientist Mary Dettman told me which flower the pollen came from. So, now we know exactly which flower this sawfly visited 15mya before it died.”

The next image Frese displays looks like an Indigenous ochre painting of a fish from a Northern Territory sacred site. “Yes, it’s made up of lots of dots,” Frese agrees. “But this is what I found more fascinating.” The subsequent image, which concentrated on the fish tail and was much magnified, has a barely discernible spot. “Let’s enlarge it even more,” Michael says. “See what it is? A new-born mussel; a tiny parasite.”

Back when it hatched, he explains, the baby mussel would have had just a few hours to hitch a lift with a passing fish on which it could survive for three–eight weeks before finding suitable oxygen-rich water to call home. “This billabong wasn’t the environment to allow a mussel to grow to maturity,” Michael continues. “So we know the fish died within three–eight weeks of the mussel attaching to its tail.”

Michael’s favourite image shows the stomach of a 15-million-year-old fish, and under the electron microscope lie the remains of what it ate before it was fossilised. “We know this fish ate lots of larvae, but see this? It’s a dragonfly wing,” he says. “We haven’t found a fossil of a complete adult dragonfly so far, but we know they were here at the billabong because we’ve found a wing inside the belly of a fish.”

Professor David Cantrill, chief botanist and director of the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria, wastes no time nominating his favourite fossil from the dig. “The fertile club moss, or Lycopodium specimen,” he says. “Fossils from this group of plants are particularly rare in rocks of this age because they’re difficult to preserve.” This weekend is David’s first visit to McGraths Flat, although he’s been documenting the flora specimens sent to Melbourne since the fossils were first discovered.

While others hammer at the virgin rocks left over from Pit I, David re-examines fragments in “the discard pile” under the she-oak. He regularly discovers botanic examples other members of the dig team have put aside for expert analysis. “These guys have been throwing all the leaf fossils here,” he says. “I’m trying to catch up by going through stuff they might have missed.” It turns out they’ve missed quite a bit in their hunt for that elusive bird that dropped the breast feather, a dragonfly or an even bigger spider.

“So far we’ve found nearly 60 species of leaf from this site,” David says. “That’s pretty unusual, but what’s even more interesting is that the botanic specimens are typical of plants that would now be found in Queensland. We can’t identify all 60 species, but we do know some, including a tangle fern [also known as pouched coral fern]. There are about 20 species of coral fern today and their stronghold is in the tropics. But only three of them are related to the fossil deposit.”

He’s particularly enthused by the flower fossils. “Generally, on this kind of site you find very few flowers,” David says. “But we’ve found hundreds of flower specimens at McGraths Flat. We’re still working out what they might be, but I’m pretty confident one is related to the Queensland bottle tree.”

All this is interesting, of course. But what has it got to do with the crisis facing the contemporary planet?

“Fossil records give us a window into past climates,” David continues. “More importantly, they point to what might happen in the future. The CO₂ levels we’re experiencing [in the 2020s] haven’t been recorded since the Miocene [23–5mya]. The difference between then and now is how quickly CO₂ levels are rising.”

“We have other Miocene fossils from Australia,” Matt McCurry acknowledges, but they’re in Queensland or the NT. “However,” he says, “we don’t have many Miocene fossils from the southern part of Australia, and certainly not in the level of detail or the range of animals and plants we’ve found here. There’s a massive gap in our knowledge of the insects, animals and plants we’ve found excavating this site.”

So, what is left to discover? “Our hope is,” he says, “that by investigating what creatures lived here 15mya we might better understand how they were affected by the changes in the environment, and why other forms of life were able to adapt and thrive in a hotter, drier climate.”