When European colonists settled in Australia it wasn’t long before they missed the comforts and familiarities of home. What followed was the introduction of many plants and animals brought over on ships.

The European honey bee (Apis mellifera) was one of them.

But unlike other introduced species we collectively agree have had a devastating impact on this country’s natural environment (eg. cane toads, rabbits, red fire ants), the honey bee is celebrated.

To mark the bicentenary of Australia’s honey bee industry, the Australian Royal Mint has even released a special edition $2 coin ‘commemorating both the remarkable creatures and their conscientious beekeepers.’

So ingrained in our society are these honey bees that it’s now hard to imagine an Australia without them.

The sweet stuff

Early settlers brought the honey bee to our shores in 1822 for one reason – they missed the sweet stuff.

Fast-forward to 2022 and the latest records show Australia is now home to 530,000 commercially-managed hives, collectively producing about 30,000 tonnes of honey each year.

It’s worth noting there are other bees and insects (both native and introduced) that also produce honey, but none to the extent that the European honey bee can, making it recognised, both in Australia and globally, as the honey bee.

Bees need two things to create honey: nectar and pollen, both collected from flowers – nectar from the heart of the flower and pollen from the anthers.

After collecting close to their own body weight in honey and pollen, the bee returns their haul back to the hive. The nectar is then passed mouth-to-mouth from bee to bee, each transfer reducing the nectar’s moisture content, until it becomes the sticky substance we call honey.

Finally, the bees store this honey in cells capped with beeswax (honeycomb).

So, what about the pollen? This is mixed with nectar to make a substance fed to the larvae.

Pollinating the economy

While the European honey bee may have been introduced to Australia for honey production, the country’s agriculture industry has also grown to rely heavily on it for crop pollination.

In 2010 an Australian federal government report concluded that about 65 per cent of Australia’s agricultural production depends on pollination by honey bees.

And it’s big business. Australia’s honey and pollination industry has been estimated to be worth $14.2 billion, while employing 1800 highly-skilled commercial beekeepers.

“Our beekeepers underpin Australian agriculture … providing Australians, and the world, with delicious honey, as well as critical pollination services for other agriculture and horticulture industries,” says Trevor Weatherhead, chair of the Australian Honey Bee Industry Council (AHBIC).

“Honey bees pollinate crops including almonds, apples, avocados, blueberries, cucumbers, pumpkins and rockmelons,” Trevor explains.

The great Aussie hobby

The honey bee holds a firm place in Australian culture, with the number of hobbyist beekeepers increasing 10-fold since the 1960s.

Data from 2021 shows at least 28,000 registered recreational beekeepers, but with a dramatic upsurge in recent years Amateur Beekeepers Australia (ABA) vice president and editor, Sue Carney, says “you could safely say Australia now has more than 35,000 recreational beekeepers.”

From rural properties to suburban backyards to urban balconies and rooftops, more hobbyists and their hives are popping up all over Australia.

“There’s a very supportive and diverse community,” Sue says.

“It’s tended to be an older demographic in the past but that’s changed. Now we see all ages – as early as school age.”

Sue started her own beekeeping club in the Blue Mountains, NSW, three years ago, hoping to attract about 10 members to join.

“We now have 164, which shows you the exponential growth of beekeeping.”

While an average-sized backyard hive can generate around 30kg of honey per year, as well as other bee products like beeswax, that’s not the only reason Australians are choosing to spend their spare time beekeeping.

“A lot of people are fascinated by bees and insects and following the behaviour and social systems,” Sue says.

“It also doesn’t take up a lot of space. If you just have a few basics, you can keep a beehive. It also doesn’t take up an enormous amount of time – more time at certain times of the year.”

Sue says it also doesn’t take long for many hobbyist beekeepers – through their study of how hives work – to gain a greater appreciation of their environment and how important pollinators are.

“They have the realisation that bees are really important as a key pollinator in our environment, then they want to help to support these pollinators.”

Doug Purdie is a perfect example of this. Starting as a hobbyist beekeeper, he soon co-founded Sydney’s The Urban Beehive with the aim of establishing beehives all over the city “to boost natural pollination and to help maintain the genetic diversity of our honeybees before it’s too late”.

“We also want to help protect local bee populations against major threats,” Doug says.

“We do this by capturing feral bee swarms to populate our beehives where possible, rather than purchasing packaged bees or queen bees from breeders. In this way we help protect the wild bee genetic lines that need strengthening in case one day the worst happens and Varroa or some other pest infiltrates our borders.”

Threats and close calls

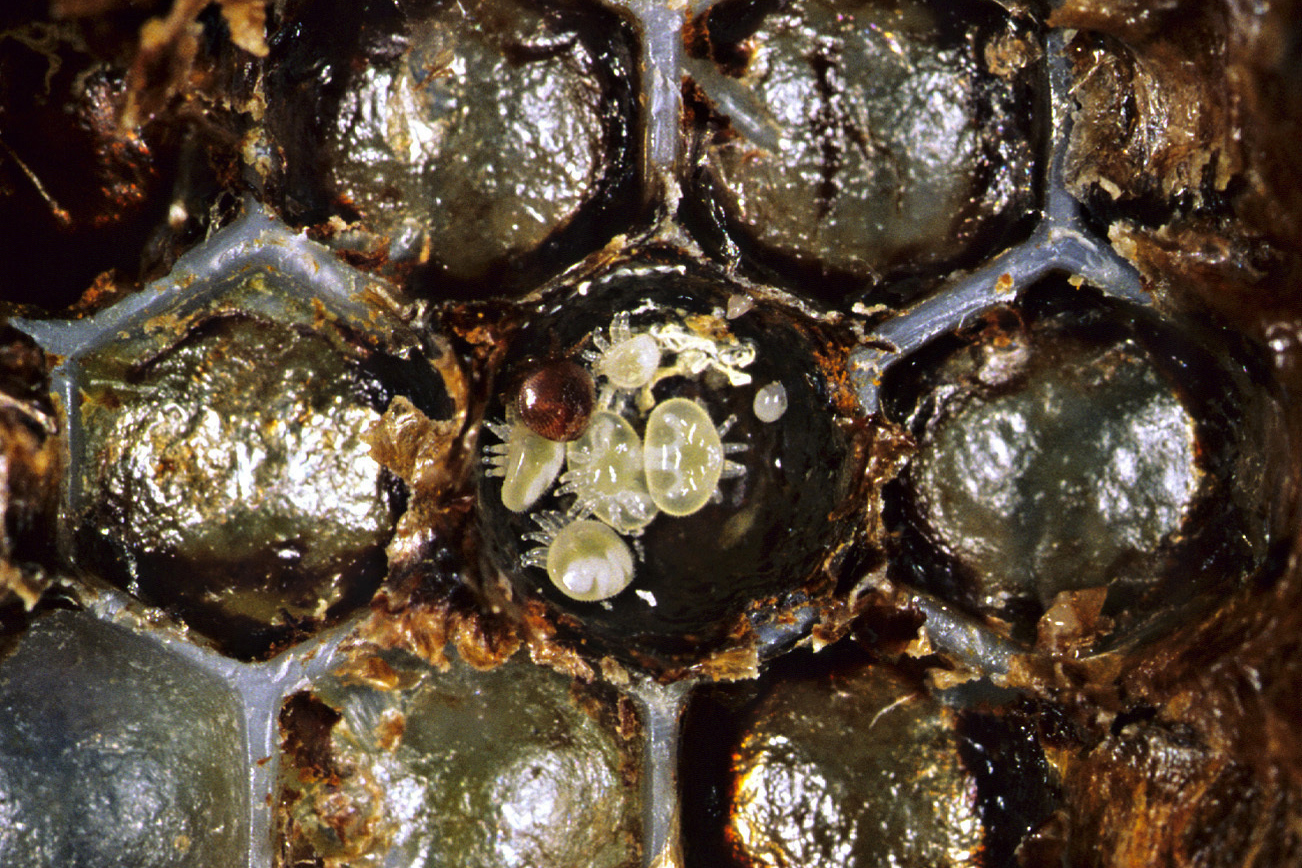

The biggest major threat to Australia’s population of European honey bees is the Varroa mite (Varroa destructor and V. jacobsoni) – a parasite responsible for the collapse of overseas bee colonies.

Incredibly, Australia is the world’s only inhabited continent free of the varroa mite, despite many close calls.

It is widely accepted by government and industry, however, that despite vigilance these parasites will eventually take hold in Australia.

While the government keeps an eye out at our ports and industry uses a range of measures to safeguard commercial colonies, Doug says there are things he and his fellow recreational beekeepers can do to keep the mites at bay.

“We need to be vigilant and check our hives routinely,” says Doug. He recommends beekeepers follow government advice on ways to do this safely and effectively.

Effect on native flora and fauna

After their introduction to Australia, it inevitably didn’t take long for European honey bees to escape managed hives and establish feral populations in the Australian bush.

Today, the number of feral colonies is unknown, but – according to the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (DAWE) – we do know European honey bees visit the flowers of at least 200 Australian plants and interact with a wide range of native flower-visiting animals.

“Feral European honey bees can outcompete native fauna for floral resources, disrupt natural pollination processes and displace endemic wildlife from tree hollows,” a statement provided by DAWE explains.

However, the extent to which honey bees can negatively impact native species, particularly native bees, is unknown.

University of New England professor Caroline Gross has been researching the impacts of introduced honey bees on native plants, animals and ecosystems since 1986.

“There’s not really one clear answer to their [European honey bees] impacts. I’ve reached the position now where I think that it’s very context specific,” says Professor Gross.

“By that I mean that it depends what type of plant species are involved and what the ecosystem type is, and whether the honey bees visiting the areas are from managed or feral hives,” she explains.

In cases where Professor Gross has found the presence of European honey bees negatively impacting native species, the most alarming involved bees literally fighting for resources.

“In a system north of Townsville the honey bees were aggressively removing the native bees from flowers in order to get pollen. They also chased the native bees around and took the pollen from the backs of the native bees.

“They were pretty desperate. In that situation it must have been that there were no better pollen resources available because the honey bee is a forager and it will always go for the easiest payload where the least amount of energy has to be expended.”

Death by bee

Two hundred years of honey bees in Australia hasn’t been so great for people allergic to them.

Unlike native bees, which are much smaller and often don’t sting, European honey bees leave their stinging barb inserted in the skin, along with a sack of venom.

Allergies to this venom are responsible for more average annual deaths than sharks, spiders or snakes separately, even though less than three per cent of Australians are allergic.

European honey bees even made a list of Top 30 Dangerous Animals in Australia – compiled by the Australian Museum in Sydney.

Museum staff rated animals out of 10 based on the threat they pose, combined with the likelihood of encountering one.